What is the highest mandate of a cultural institution? The most obvious answers might be to collect, conserve, and present culture. But to preserve and display objects does not give them meaning, and for institutions to imagine that this is their true calling puts them on equal footing with the average encyclopedia—staid, silent, and itself an object.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if, above even preserving and collecting, the highest mandate of cultural institutions were producing new knowledge? What if these institutions put the objects in their possession to work? Perhaps they might begin establishing helpful rejoinders to the question cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter often poses: “How can we be human together differently?” Differently, not better. This is not necessarily the result of linear solutioneering but rather a set of tools forged in the pursuit of transformation.

Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, opening February 27 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, will offer tools rather than solutions. Curated by Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson, the show has been in the works for well over two years—surprisingly, since it feels very much of the moment, not just in its themes but also in its staging at MoMA. Following the Black Lives Matter demonstrations last summer, many institutions rushed to highlight their attempts at diversification, decolonization, or damage control but failed to produce alternative paths forward. However, outside forces had a few ideas of their own. In late fall, several contributors to Reconstructions reignited the call for administrators to strip MoMA’s architectural department of the name of its founder, acknowledged Nazi sympathizer Philip Johnson. (MoMA has yet to comply with the demand.) If the words of its curators and those printed in the accompanying “field guide” are any indication, Reconstructions promises to put the institution’s legacy and future in productive tension.

Reconstructions is the fourth installment of the Issues in Contemporary Architecture series, which kicked off at MoMA in 2010. The series has presented sea-level rise in New York, foreclosure in the U.S. housing market, and tactical development for global megacities as urgent problems in need of design responses. Reconstructions deliberately takes a different approach, said Anderson, MoMA’s associate curator for architecture, who found that the series “didn’t necessarily find its purpose in the interface with the community but rather…became this relay between the curator and the architects.” By dropping the design-as-solution framing, he and Wilson, an architect and professor of African American and African Diasporic Studies at Columbia University, were able to position Blackness as an analytical lens through which to deconstruct—and possibly reconstruct—the built environment.

The exhibition is a natural continuation of Darby English’s 2019 study Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, which revealed the lack of Black creators present in MoMA’s archives. The two projects share some contributors, including Wilson and Anderson themselves. Commissioned by the museum, Among Others doubles as a body of evidence and a demand: do something about this. The exclusion of Black artists, architects, and designers’ work from the United States’ most prominent archive of the modern revealed its foundational curatorial attitudes—such as those held by Johnson.

But English’s work also interrogated the museum’s foundational mission. Rather than elevating and archiving the modern, MoMA has carved a rather small keyhole through which portions of it can be observed. Reconstructions seeks to widen that scope of vision. Of course, to bring an architecture exhibition showcasing Black critical thought to an institution whose decision-making, critical references, and archive are shepherded predominantly by white people is no easy task. When I asked what it took to bring such a show to West 53rd Street, Wilson emphasized a change in orientation, away from “the notion of liberal individualism” toward an insistence on the collective. Individuals are easy enough to omit—one person fired, one piece rejected, one file lost from the archive. But the collective is not so easily dismissed. In the collective, Wilson saw an opportunity to “challenge white supremacy [in a way] that draws in the pain of anti-Black racism but also the beauty and resilience of Blackness.” It’s an idea that generated the critical position for the exhibition.

To ensure that this position lived at the core of the show, Wilson and Anderson established an advisory committee prior to selecting contributors for the exhibition. This committee included academics like education and economics scholar Richard Rothstein, English and real estate scholar Adrienne Brown, and English and Black-studies scholar Christina Sharpe. In short, heavy hitters of contemporary critical race discourse. Pushing past disciplinary divisions, the group engaged with Black critical thought from the fields of design, literature, architecture, and visual art. From these conversations were born the themes that would organize the exhibition: refusal, liberation, imagination, care, and knowledge. The curators then encouraged the show’s contributors to work with these broad themes as they would work with a site.

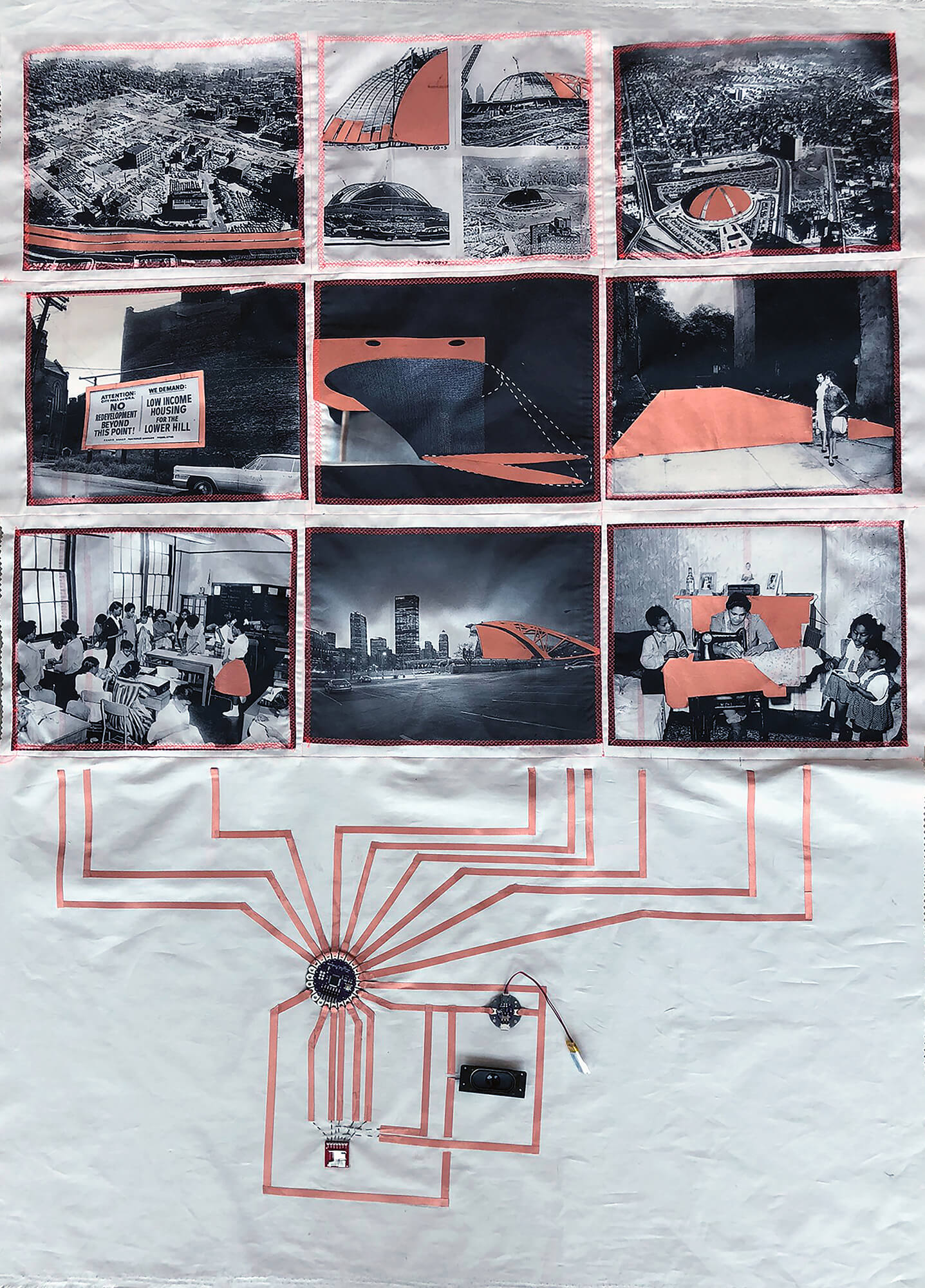

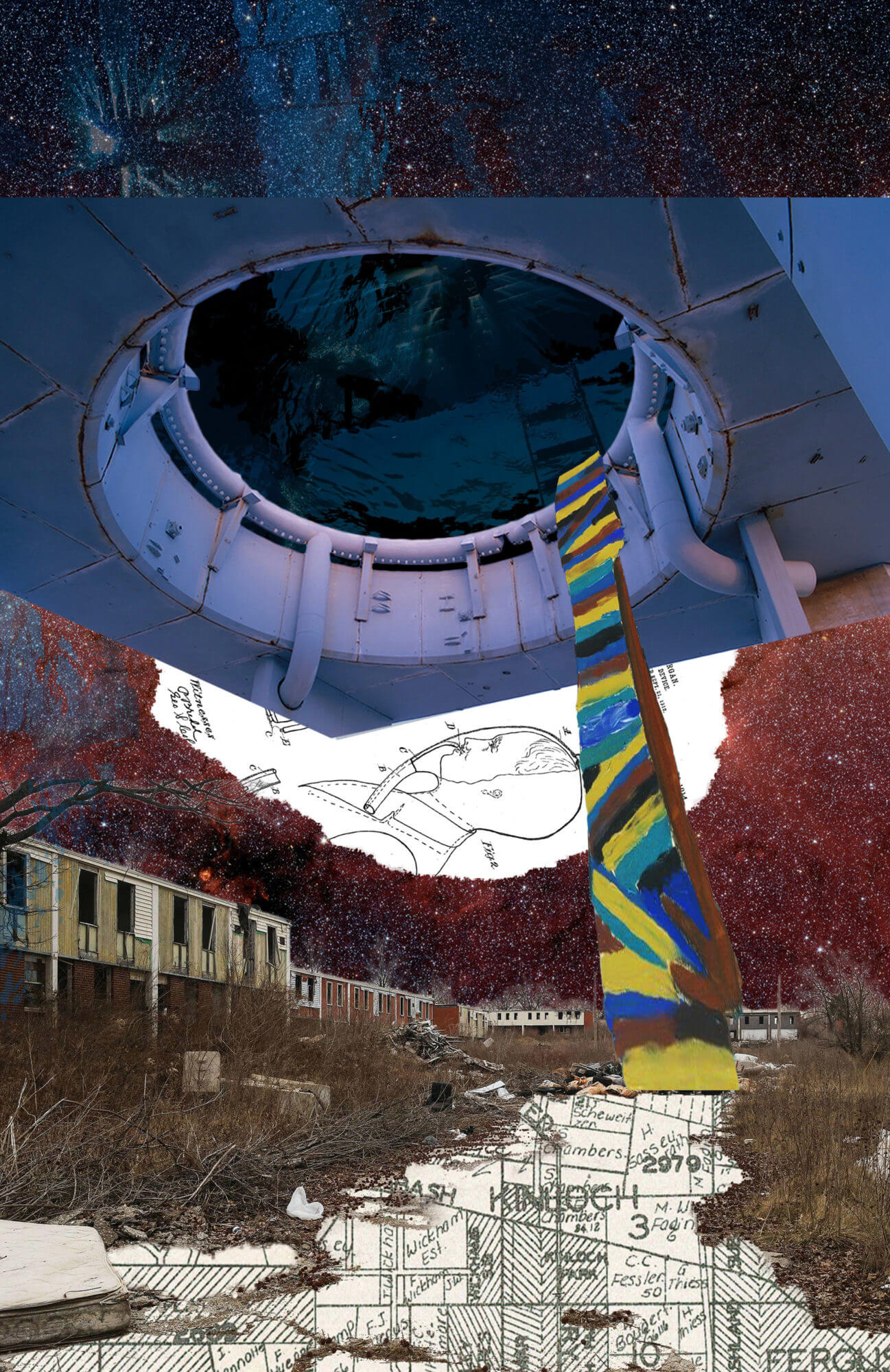

In a series of immersive mappings, Emanuel Admassu refuses to measure the fragments of Black Atlanta. Putting W.E.B. Du Bois and Richard Wright in conversation, Adrienne Brown liberates the Reconstruction era from easy explanation. Germane Barnes wades across kitchens, porches, and shorelines to imagine a Black taxonomy of Miami. In verse, Amanda Williams takes care to misdirect her reader to Black space. Documenting her 2018 MoMA PS1’s Young Architects Program installation (one of the last in the series), Jennifer Newsom acknowledges architecture’s reliance on boundaries—and erases them.

The exhibition is designed such that no piece is viewed in isolation; instead, the design implies sightlines to related projects, further emphasizing collectivity. These pieces and the process that brought them together hint at the possibility that institutions like MoMA can produce new forms of knowledge. But Robin D. G. Kelley, who wrote the field guide’s preface after an ailing Toni Morrison graciously declined, disagrees. “The people carry that mandate,” he said before clarifying that “collectivity must also be a place of tension.”

In other words, being in the collective is not always being in agreement. The tension that arises from this is the recognition of difference, which creates the opportunity to react to and build on that difference. Those reactions, those debates, those frictions that collectivity exposes can facilitate transformation. This is exactly what Wynter encourages the cultural sector to reach for. Transformation is the cost of being human together differently.

The collectivity of Reconstructions is an invitation to transform. The question now is whether the institution will take the collective up on it or, in refusing, atrophy before the evolving crises of our time. When I asked Anderson whether Black critical thought would be part of the architectural department’s curatorial approach going forward, he wavered. “It has no doubt transformed my thinking,” he said. “Does Black critical thought get situated in a more fundamental manner in the institute writ large? Hard to tell.” With Philip Johnson’s name still prominently featured on the museum’s galleries and offices, it is, indeed, hard to tell.

Jess Myers is an editor, writer, and podcast producer based in Brooklyn. She is the co-steward of New York’s Architecture Lobby chapter.