The clue is in the name. The Philadelphia-based architecture firm DIGSAU (think “dig” and “saw”) creates buildings that feel handmade. There is an overt concern for variation and texture, often expressed on the enclosures of projects—at a facility for a Delaware vocational school, for instance, that sports what seems to be an improvisatory rainscreen of mismatched wooden planks. Meanwhile, the outer faces of a woodsy villa are purposefully roughed up to match the coarse, flecked bark of the surrounding trees. And charred cedar and weathered steel complement the otherwise clean lines of a Philadelphia bird sanctuary.

But for all this affected ruggedness, the buildings betray a keen knowledge of industrial materials and how to use them. For every rubble stone facade in the DIGSAU catalog, there is a cunning yet still economical display of precast concrete. As the firm has scaled up—it has several projects in the works at the Philadelphia Navy Yard mega-development—the moments of intense surface texture have grown less profuse, if not curtailed altogether. “We’re very conscious about where we spend money on projects,” said DIGSAU’s Mark Sanderson. “We don’t equally spread the money over the entire project. We are very deliberate about spending more money on specific places where it’s going to be recognized.”

Profile and massing are just as key to the firm’s work. A spa and amenities complex at a Philadelphia condo development finds Sanderson and his co-principals Jules Dingle, Jeff Goldstein, and Jamie Unkefer at their most exuberant. Giant shardlike wedges, containing sunken pools and changing rooms, rise up from the hardscape in a showy, yet still grounded, gesture, and the light reflecting off the pool water and porcelain tile cladding is more evocative of Portugal than Philly.

All of DIGSAU’s founders were at one time on the payroll of Philadelphia powerhouse KieranTimberlake before striking out on their own. They started up shop in the auspicious year of 2007 and were only able to ride out the recession by “looking afield and moving outside of our comfort zone and wheelhouse,” said Unkefer, pointing to a pair of breweries they designed. “We’ve made the analogy to the craft brew movement, where you suddenly had a consciousness of ingredients and tying into traditions that are less industrialized.”

Philadelphia’s excellent restaurant and drinking scene is part of what’s driven the city’s image change of the past decade. DIGSAU’s portfolio reflects that change, perhaps to an uneasy degree. “A working-class mentality permeates the city that we wouldn’t want to lose,” said Sanderson. “It’s certainly embedded in the way we think and work. Our work is a little messy for a reason.”

Clay Studio, 2021

Work is underway on The Clay Studio, a 34,000-square-foot ceramic facility in Philly’s South Kensington neighborhood. Grayish bricks are used on the building’s outer walls, while public spaces and a roof garden are lined with sculpted clay tiles. For Unkefer, who was a professional potter before pivoting to architecture, the project “offered an opportunity to connect my interest in ceramics to the city’s incredible tradition of brick masonry.”

Iovance Life Science Headquarters, 2021

This 135,000-square-foot lab-and-research facility is DIGSAU’s fifth project at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, a multiphase effort to redevelop a centuries-old naval shipyard in South Philadelphia. The public-private venture, which is entering its next, $2.5 billion phase, features hulking offices and landscapes, the latter designed by James Corner Field Operations.

Sitting at the edge of the central lawn, the Life Science Headquarters presents a striking architectural identity that helps set off its program. On the three-story main building, spindly steel fins surround glazed units; the same rhythmic pattern is picked up in the adjacent, one-story loadbearing concrete structure. “The two really weave together,” said Sanderson. “The team searched for ways to amplify what that precast could do.”

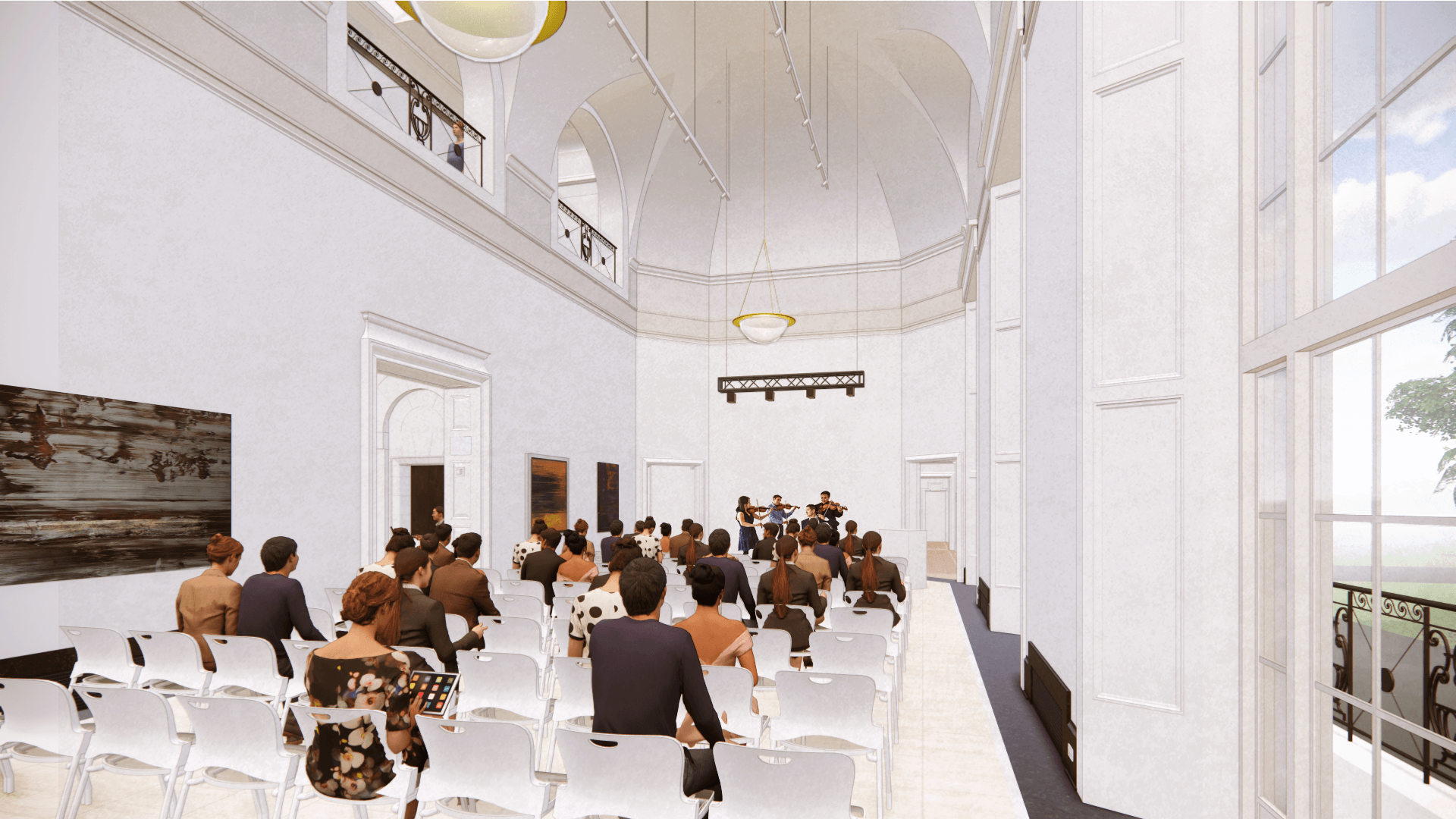

Frances M. Maguire Art Museum, 2021

In 2012, the famed Alfred C. Barnes Collection was relocated from a nearby suburb and meticulously restaged in a new downtown Philadelphia facility designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects. As stipulated by the crotchety Barnes, artworks and gallery walls could never be parted; so off they went, leaving behind “this really beloved old building,” said Unkefer. DIGSAU is in the process of renovating the galleries, which will be taken over by Saint Joseph’s University. “It’s a mindbender,” Sanderson added. “It’s a ghost building, a kind of an echo of the past.” The whitewashed interiors are the most marked change, but the architects will also be enhancing handicap accessibility and clarifying gallery circulation routes.