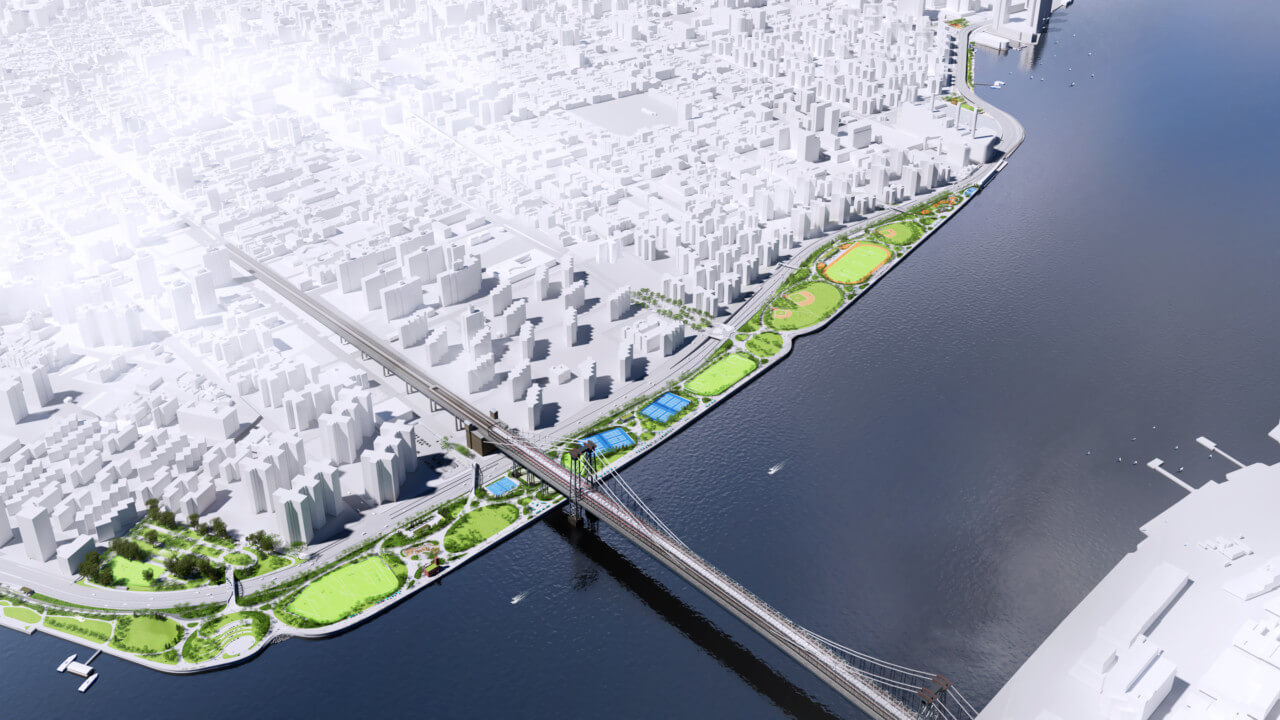

Construction is underway on the $1.45-billion East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project, initially envisioned by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and One Architecture & Urbanism as part of “The BIG U.” The design scheme, developed to protect 10 continuous miles of New York City waterfront, stretching south from West 57th Street to the tip of Manhattan and up to East 42nd Street, from floodwater, storms, and other threats posed by climate change, was one of ten finalist projects selected through the Rebuild By Design competition, an initiative launched by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development in response to the devastating impacts of Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

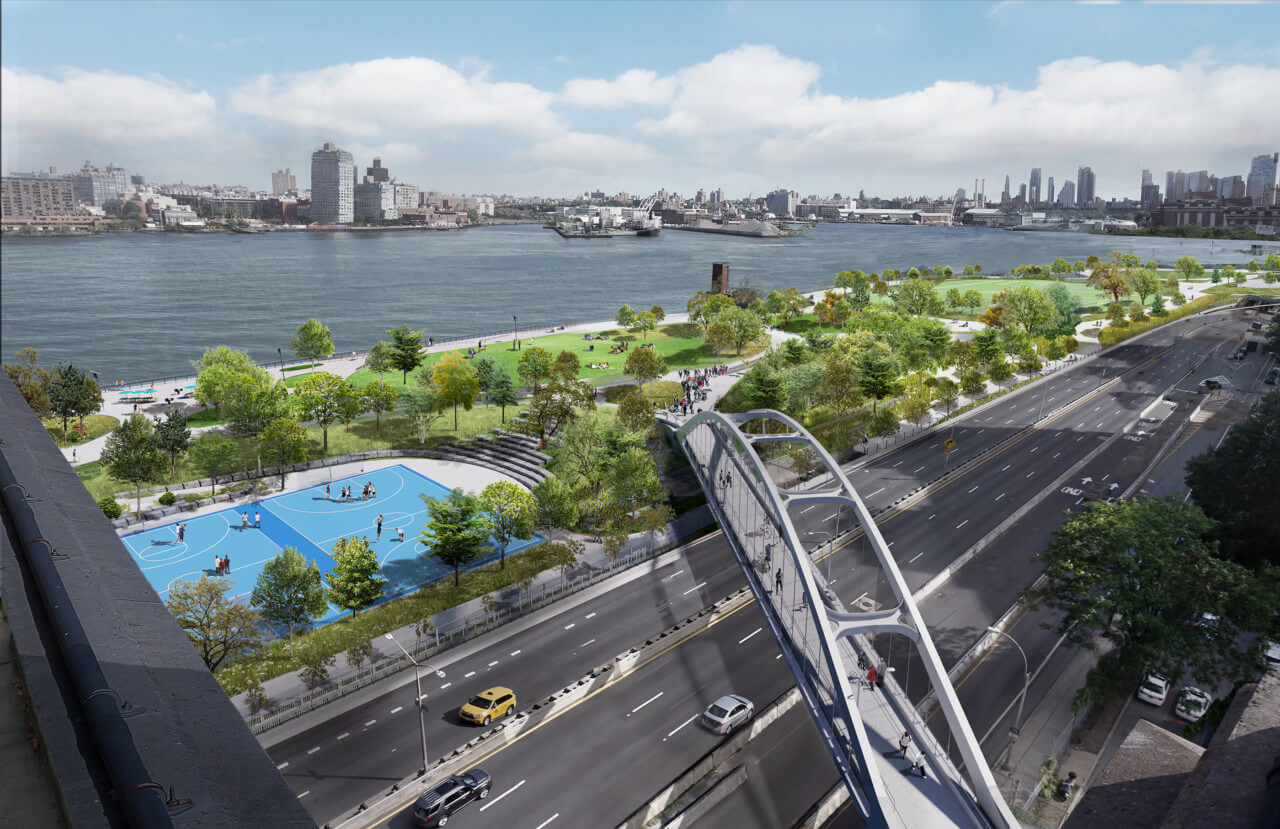

The ESCR Project is the first phase of the city’s efforts to enhance flood resiliency in Lower Manhattan. In a press release from April 15, the city detailed that improvements to the 2.4-mile-long stretch of Manhattan’s East River shoreline will include: Enhanced accessibility to Corlears Hook Park and a redesigned Corlears Hook Bridge; updated facilities at Murphy Brothers Playground, including ballfields, a basketball court, and a dog run; floodwalls and floodgates at Stuyvesant Cove Park and Asser Levy Playground; a rebuilt and expanded Solar One Environmental Education Center, and more. In addition, the city plans to construct dedicated pedestrian and bike paths on the Manhattan Greenway that runs along the western edges of East River Park and Stuyvesant Cove Park. Another key component of the project, one that has provoked controversy, involves burying the existing East River Park under soil and elevating it by 8-to-10 feet above sea level. The reconstructed park will feature new amenities, including upgrades to the amphitheater, playground, picnic areas, basketball courts, soccer fields, and multi-use turf fields.

Jainey Bavishi, director of the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, touted the community’s collective effort in realizing the ESCR Project and stated in the same press release that, “Years of collaboration among the City, community members, and local leaders have enabled this bold and visionary plan, which integrates flood protections seamlessly into New York City’s urban fabric while renewing and strengthening beloved public spaces like East River Park.”

Though community groups, including East River Park Action and the East River Alliance, acknowledge that measures must be taken to address climate change and flood vulnerabilities in Lower Manhattan, they question whether the current plan is the best approach for doing so. The city’s handling of the decision-making process remained a point of contention. Residents claimed the city had failed to sufficiently convey its rationale for abandoning an earlier coastal resiliency plan, which had been developed in collaboration with community members and local stakeholders over the course of several years.

The previous design scheme, scrapped in 2018, called for the installation of berms and flood barriers along FDR Drive and would have preserved much of the existing East River Park. At $760 million, it also would have cost the city far less.

Community members also expressed dissatisfaction for an alleged lack of transparency on the part of city officials. Earlier last month, the East River Action group sued the City of New York, demanding that redacted portions of East Side Coastal Resiliency Project’s “Value Engineering Study,” the report Mayor de Blasio cited as supporting evidence for the city’s need to alter course on the project, be made public. In a letter to the mayor dated April 5, Justin Brannan, Chair of the Committee on Resiliency and Waterfronts, wrote, “as an advocate for climate adaptation and resiliency, and as someone who has not taken a position on this project, I too wish to see that the initiative will live up to its resiliency goals, and that the city’s investment is worthwhile from a sustainability standpoint.”

Some residents claimed the environmental ramifications of burying the park and felling approximately 1,000 trees had not been thoroughly assessed and that more measures were needed to conserve and relocate existing wildlife. Dr. Amy Berkov, a City University of New York biologist and East Village resident, questioned why the city neglected to follow the regulations set forth in the City Environmental Quality Review Technical Manual, which provides agencies guidelines to evaluate, disclose, and mitigate the environmental consequences of a project before it is implemented. An executive summary from 2019 on the environmental impacts of the project claimed that all birds and insects could migrate to nearby tree canopies and community gardens throughout the duration of construction, and that “no significant adverse effects to terrestrial resources are anticipated as a result of construction.” Though the city has committed to planting approximately 2,000 new trees, consisting of fifty different tree species that will be more resilient to salt spray and extreme weather, it will take decades for the new saplings on the reconstructed park to achieve a full canopy.

The city anticipates that the project will be completed in 2025, but some critics have raised concerns that the financial crisis caused by the pandemic may cause delays, denying residents a valuable green space for years to come. Following previous community opposition to the city’s plans to close the park completely for 3.5 years, the city adopted a phased construction approach to ensure that approximately half of the park remains open at any given time.

Additionally, others questioned if raising the park by 8-to-10 feet at a cost of $1.45 billion will be enough in the long term, when the New York City Panel on Climate Change released a report in 2019 stating that the city may be threatened by 9.5 feet of sea-level rise by the end of the century. Though this is a low-probability scenario and knowledge of ice loss processes and ice sheet interactions remains incomplete, the report claimed that city planners should be aware of the growing risks.

On April 18, hundreds of community members marched from Tompkins Square Park to East River Amphitheater to voice their opposition to the ESCR Project. Many of the marchers also staged a “die-in” outside of Councilwoman Carlina Rivera’s office. In response to the protests, Councilwoman Rivera told amNewYork and Gothamist that the city “will not let the protection that our public housing residents deserve and that has been denied to them for nearly a decade be allowed to be delayed any longer.”

At Project Area 2, between East 15th and East 25th Street, pile driving operations and preparations for floodwall foundations at Stuyvesant Cove Park and Asser Levy Playground continue to proceed, but protestors remain hopeful that the city’s next mayor will reconsider the project. Representatives from the Department of Design and Construction confirmed last month that Project Area 1, encompassing East River Park, is still in the bidding process and will not be commencing this spring as initially planned.