What do the United States Supreme Court, Jefferson Memorial, and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington Cemetery have in common?

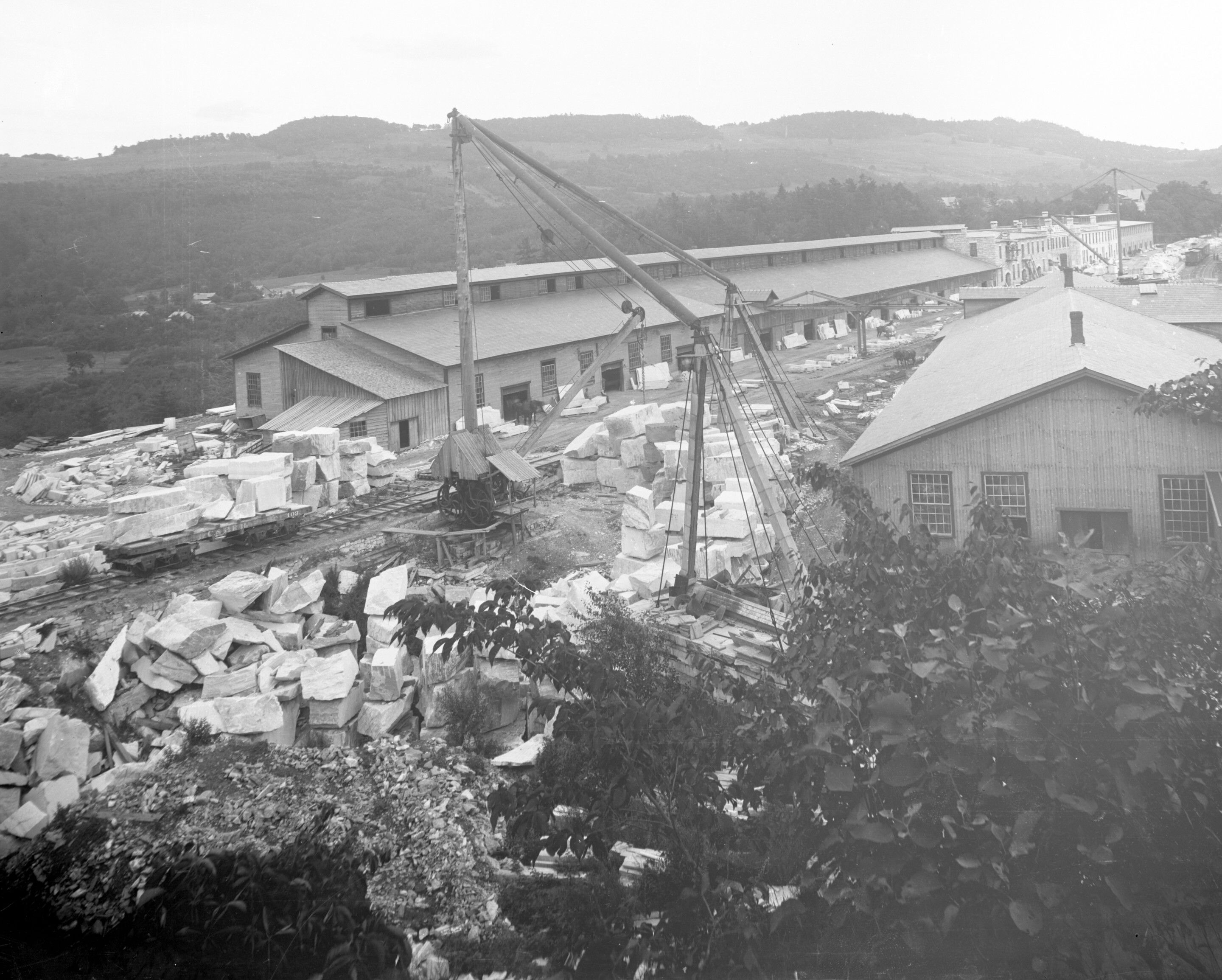

In a word: Marble. Not just that, but all three are built with marble that was quarried, cut, and sculpted by the crews of the Vermont Marble Company (VMC). Last week, the Preservation Trust of Vermont (PTV) announced that it is soliciting proposals for a 2-story, 87,275-square-foot industrial building on a 3.15-acre site in Proctor, Vermont, that was once used as the VMC headquarters. The goal of the RFP is to field ideas from architects, designers, and interested backers that could breathe new life into the industrial heritage site. Today, the complex, which was recently stabilized over a ten-year preservation effort by PTV, is home to the Vermont Marble Museum (VMM) and several other tenants.

Ben Doyle, PTV President, told The Architect’s Newspaper, “Our goal [is] to preserve a critical piece of Vermont’s (and the nation’s) history and spur additional economic activity in Proctor,” adding, “For a variety of reasons, we now see that skills and effort required to interpret an industrial heritage site as a museum are not necessarily the same as managing a 90,000-square-foot building. That’s why we have decided to issue an RFP to find a new partner that can work collaboratively with the Museum’s board. This approach allows VMM to tell the story of Proctor, including the geology of the place, the industrial history, as well as the social and political history of the Vermont Marble Company.”

The Vermont Marble Company was created in 1880 by Redfield Proctor, a Civil War veteran from a prominent local family who would go on to serve as the Governor of Vermont, Secretary of War to President Benjamin Harrison, and the state’s US Senator. Proctor brought together a series of fledgling industrial operations to vertically integrate marble quarrying activities in the area, creating a sprawling quarrying behemoth that supplied public and private clients across the United States with fine-grained white marble. At the height of its productivity, the VMC was considered the largest U.S. corporation in the world, according to the Vermont Marble Museum website, and held exclusive mining rights to all marble deposits in the states of Vermont, Colorado, and Alaska. Using this broad network of quarrying facilities, VMC would provide building materials for prestigious building projects, including the Oregon State Capitol, the Arlington National Cemetery, and Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. As the United States sought to erect new national monuments at the dawn of the 20th century in Washington, D.C., and beyond, it often did so not only in marble, but stone quarried by VMC, specifically.

Although the material is perhaps best known for its use in symbolic projects—the monumental Ionic columns and exterior walls of the Jefferson Memorial are crafted from white Vermont marble, for example—over the decades, VMC marble found its way to buildings across the country. In trade publications like AIA Journal and others, VMC often took out full-page ads highlighting its products under the trade name “Vermarco” in an attempt to communicate a more modern aesthetic. Milled into 1-¼” veneer panels, Vermarco marble found its way to public school buildings, post offices, banks, office lobbies, and all manner of other structures and spaces across the country, offering a sort of stealth ubiquity alongside other more well-known other American industrial building components, like Otis elevators or General Electric lightbulbs.

That anonymity may change with the new push by the Preservation Trust of Vermont to reimagine the VMC site. The RFP website explains that PTV “not seeking a purchase offer, but rather a full proposal including proposed scope and end use” with the expectation being that the proposal contributes productively to the economic and cultural future of Proctor and the surrounding county. The site explains that priority will be given to proposals that show interest in operating the building to support the economic and community development goals of the town and that keep the Vermont Marble Museum in place.

When asked what he’d like to see in potential RFP responses, PTV’s Doyle explained, “To get real specific, I could see some wonderful intersections between industrial heritage, new creative practices, artistry, and outdoor recreation (it is Vermont, afterall),” adding, “At this point, we are waiting to see what compelling ideas are out there.”