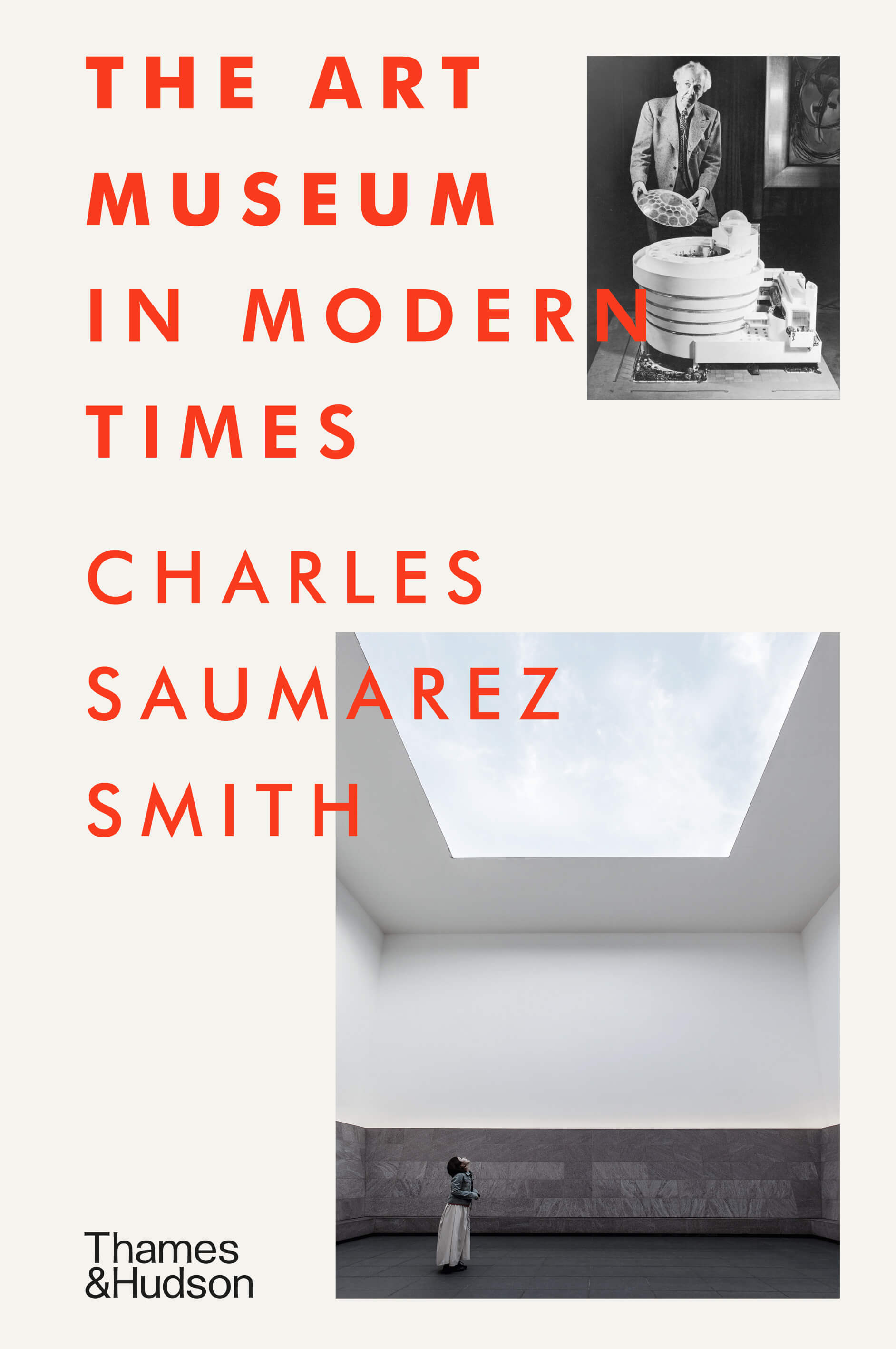

The Art Museum in Modern Times

Charles Saumarez Smith

Thames & Hudson

MSRP $40

Is a museum defined by its collection? Or by its architecture? In The Art Museum in Modern Times, Charles Saumarez Smith suggests it is both and still something more. Trustees, administrators, and curators have done the most to alter the face of art institutions over the 80 or so years that make up Saumarez Smith’s timeline. Throughout, the art historian and former director of the National Portrait Gallery in London attempts to glean, from built form, the “evolving aims, aspirations and beliefs” of these actors. Yet in his privileging of conciseness, he omits the complex balancing of interests and influences needed to realize any museum project. These, it should be noted, often extend well beyond museum leadership.

The book’s structure is straightforward, comprising case studies that span public and private institutions, the canonical and the lesser known. More enigmatic is the periodization to which the title alludes. The 40-plus museum buildings that Saumarez Smith surveys are heterogeneous, stylistically evoking both modernism and postmodernism, as well as the yet-to-be-codified idiom of the “new millennium.” It quickly becomes apparent, however, that the catchall signifier “modern” is a nod to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Marking a break from the “traditional museum,” Saumarez Smith’s close reading of MoMA recounts the fledgling institution’s efforts in the 1930s to seek a streamlined architecture to match its novel and unorthodox curatorial program. Although a predictable starting point, the museological template established by MoMA effectively captures the institutional histories that follow.

If modernist spatial logics linking form and function long determined the baseline for museum architecture, they have given way to something less cut-and-dried. Already in 1990, the art historian Rosalind Krauss identified a new consumerist logic at work in the spaces of the “late capitalist museum,” a thesis further explored in Hal Foster’s 2011 The Art-Architecture Complex and Claire Bishop’s 2013 Radical Museology. Saumarez Smith makes mention of this development, whose repercussions are many: Today’s museums are no longer preserves of high culture, nor do they espouse articles of faith in the public good. Rather, they find themselves forced to compete in an attention economy that revolves around individualized experiences and product placement. And if museums once relied on architecture for their mooring, the opposite is increasingly true. For instance, Marcel Breuer’s 1966 Brutalist building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, home to the Whitney Museum until 2015, has become something more akin to a rotating, kunsthalle-style gallery, having played host to exhibitions from the Met’s modern and contemporary holdings and recently reopened as the Frick Collection’s temporary home.

A consummate industry insider, Saumarez Smith would seem a potentially compelling guide to navigate these changing priorities and dynamics. It’s a shame, then, that The Art Museum in Modern Times doubles down on timeworn narrative devices. The chronological unfolding of the case studies is clear enough to follow—even for those unfamiliar with 20th-century art history—yet the more keyed-in reader is left wondering what more might have been gleaned if the museums had been organized thematically, i.e., according to type, context, or institutional focus. Though the book purports to be global in scope, it hews to a U.S. and European context and is premised on personal judgments. The sundry museums, renovations, and additions that make the cut are simply those the author “admire[s] or think[s] are important.” Given this bias, and the current expansionist zeal of art-world institutions, it isn’t surprising that the same handful of institutions (or brands) crop up more than once. The architectural analysis so proffered leaves unexplored the co-constitutive role art and architecture have in framing visitor experiences. Instead, the book progresses from one capsule history to the next, yielding a cavalcade of names, dates, and high-minded statements about the museums’ place in civil society.

In the epilogue, Saumarez Smith suggests that museums are now “under attack” from political, technological, and economic forces. He contemplates the changing nature of art displays, the financial constraints and pressures in an increasingly globalized world, and the demotion of art’s status to a form of entertainment. Compounding these are the emergence of numerous, better-informed publics, whose concerns about the sources of donor wealth, demands for the repatriation of colonial artifacts, and calls to dismantle the canon threaten the institutions to which Saumarez Smith has devoted his life. (In addition to the National Portrait Gallery, he has occupied leadership positions at the National Gallery and the Royal Gallery.)

Though he raises the alarm, his closing sentiments amount to a predictable punting of responsibility. Reinvention might be inherent to the modern museum, yet it falls to “a new generation of architects, trustees, and museum directors [to react] to the changing demands of their publics,” Saumarez Smith concludes. However, this generational approach to change is slow-moving. Museum commissions are beyond the reach of most firms, and those with the portfolios and profiles that typically warrant consideration tend to be older and whiter. Museum leadership, including trustees and directors, suffers from the same lack of diversity. Addressing the current challenges facing art museums will require fresh perspectives and an openness to structural change.

The pandemic offered a glimpse into a future in which museums have become “disembodied,” both from their host architecture and from their collections. Owing to enforced lockdown measures, institutions retooled exhibitions for digital formats, diversified their programming, and developed new platforms for outreach. For many, these changes will undoubtedly have lasting effects. Yet the opportunity still exists to go further; as museums reopen, they should reconsider architecture’s utility not just in protecting the health of staff and visitors but also in welcoming those who have been traditionally shut out.

The Art Museum in Modern Times is filled with historical photographs, design sketches, architectural models, and portraits of museum patrons and architects. After a year of quarantine, travel restrictions, and shuttered doors, it will doubtlessly appeal to arts and culture enthusiasts, or anyone seeking vicarious thrills. But the past year has also made our woeful lack of support for cultural institutions and our society’s failings at equity and inclusion all the more obvious. Can we continue to engage in a form of escapism that denies these very realities? Rather than pine for all that we have missed, we should keep the pressure on institutions to initiate much-needed change. As we begin the process of reentering and reengaging civic space, nothing is more vital.

Lauren McQuistion is an architectural theorist, historian, and designer currently PhD-ing in Charlottesville, Virginia.

AN uses affiliate links. If you purchase something through such a link, AN might receive a commission.