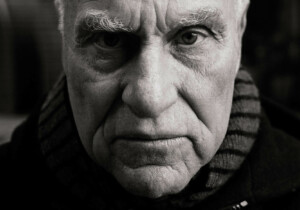

Thomas Gordon Smith, an architect and educator who played a key role in the resurgence of classicism in American architecture, passed away in South Bend, Indiana, on June 23. He was 73.

Born in Oakland, California, on April 23, 1948, Smith earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of California at Berkeley and started his own practice in 1980. He taught at the College of Marin; SCI-Arc; UCLA; Yale University and the University of Illinois at Chicago before becoming professor and chair of Notre Dame’s architecture school in 1989.

From 1979 to 1980, Smith was a Rome Prize Fellow in Architecture at the American Academy in Rome, and that is where he became fully committed to the profession of classical architecture.

As professor emeritus and former chair of the School of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame just outside of South Bend, Smith shaped a curriculum that made Notre Dame a leader in the revival of classical architecture.

Serving as chair from 1989 to 1998, he restructured the School of Architecture as an academic entity independent of the College of Engineering, where it had been, and brought like-minded educators to campus. He steered the School of Architecture away from the modernist concentration that many schools offered at the time and in a direction that made it one of the primary institutions in the United States for the study of classical and traditional architecture.

In short, he gave Notre Dame’s School of Architecture a new brand, prompting The New York Times to call it the “Athens of the new movement” in 1995. The same Times article christened Smith as one of “Architecture’s Young Old Fogies,” part of the “reticent revolution” of “antediluvian Vitruvians” that some call “the New Classicists” and “true visionaries” but others dismissed as retro. “The whole idea of doing something original is so old now,” the Times quoted Smith as saying.

Smith, who always wore bow ties and referred to bedrooms as “cubiculum,” took the New Classicist ball and ran with it.

“What we were able to do is change to a classical perspective, which means responding to and reanimating antiquity as well as the Renaissance and, certainly, the period during the 1800s and later within the United States,” he said in a 2016 interview with Traditional Building Magazine.

Notre Dame, looking to strengthen its program with new leadership, backed the change in direction. “We were fortunate to have terrific support at the top level of the university,” Smith told the magazine. “Their help, the aid of some of the existing faculty, and the development of the new faculty, really made the classical program a possibility.”

“Thomas had a tremendous impact on the trajectory of the architecture program at Notre Dame,” said Stefanos Polyzoides, the current Francis and Kathleen Rooney Dean of the school, in an article published by Notre Dame News.

“His commitment to classical architecture has inspired generations of students and his foresight in creating this program has had a transformative impact on the field. I greatly admired Thomas and respected him as both a practitioner and an educator.”

“Thomas Gordon Smith brought a new vision to the architecture program at Notre Dame, and brought me and many of my colleagues to the University,” Michael Lykoudis, professor and former dean, told the university publication.

“We all owe much to Thomas; he was a valued colleague and a friend,” Lykoudis added. “He was instrumental in rebuilding a culture of classical and traditional architecture that went beyond style, to the heart of what it means to be an architect in contemporary society.”

“A great light has gone out in the world with the passing of Thomas Gordon Smith,” tweeted Denver architect and educator Christine Huckins Franck. “He created Notre Dame’s Classical architecture program and will forever be the intellectual spirit and driving force of the contemporary Classical renaissance.”

Former student Mark Foster Gage called Smith a “huge mentor of mine” and an “amazing architect.” On his Instagram, Gage posted a photo of his “dogeared to death” copy of Smith’s 1988 treatise Classical Architecture: Rule & Invention as a tribute.

“While most people don’t know of his work—he likely changed the profession more than most far-more famous architects in the last 30 years,” Gage, who graduated from Notre Dame in 1997, told AN.

“I say this because he’s the person who single-handedly turned Notre Dame into a classical architecture program, and they’ve been pumping graduates into the world with these highly unusual but very sought-after skills for three decades.”

Smith “literally re-booted the program there on an entirely classical operating system, hiring the few practicing classical architects that were teaching, and producing a curriculum that’s unique in the world,” Gage added. “If each class graduates about 40 people, as a guess, then that’s 1200 classically-trained architects in the world that would not be so trained had it not been for him. It’s the only school teaching this material, in the old-school Ecole Des Beaux-Arts manner.”

According to the website of his office, Thomas Gordon Smith Architects, his projects in Italy culminated in an exhibition on the “Strada Novissima,” part of a show called The Presence of the Past at the 1980 Venice Biennale.

In Classical Architecture: Rule & Invention (Peregrine Press, 1988), Smith advocated that architects learn the classical language for application in contemporary design. In Vitruvius on Architecture (Monacelli Press, 2003), he promoted classicism by analyzing the Roman architect who wrote a prescription for the renewal of architecture in the 1st century B.C.

Smith’s own contributions were highlighted in Thomas Gordon Smith: The Rebirth of Classical Architecture, a 2001 monograph by University of Miami professor Richard John.

Smith’s influence is also reflected in more than 20 museum exhibits and in scholarly publications of his research. According to Notre Dame, his areas of expertise included American Domestic Architecture; Classical Antiquity; Classical Architecture; Furniture Design; Professional Practice; Renaissance and the Baroque, and Sacred Architecture.

Smith served on the boards of The Society of Architectural Historians; the San Francisco Architecture Club; the Society for Catholic Liturgy and the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. From 2006 to 2008, he was an Architectural Fellow for the U. S. General Services Administration.

As head of his own practice, Smith designed dozens of ecclesiastical, public and residential projects across the country but mostly in the Midwest. His ecclesiastical projects include a new church, parish hall and education building for St. Joseph Catholic Church in Dalton, Georgia; Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary near Lincoln, Nebraska, and Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey, a Benedictine monastery near Tulsa, Oklahoma.

His public projects include the Cathedral City Civic Center in California and visitor centers for the Lanier Mansion Historic Site and the Decatur County Historical Society Museum in Indiana. At Notre Dame, he designed the Alliance for Catholic Education’s Carole Sandner Hall; the master plan and the Our Lady of Sorrows Mausolea for the Cedar Grove Cemetery, and an addition to the Bond Hall School of Architecture.

Smith retired from professional practice in 2015 and from Notre Dame in 2016. He is survived by his wife of 50 years, Marika; a sister and brother; six children and 10 grandchildren. His funeral services took place on June 29 at Notre Dame’s Basilica of the Sacred Heart, followed by burial at Cedar Grove Cemetery in South Bend.