Before May 31, 1921, the predominantly African-American Greenwood section of Tulsa, Oklahoma was a flourishing commercial and residential district. Barred from most aspects of public life and threatened by the violent enforcement of Oklahoma’s unjust Jim Crow legal system, Black residents cultivated a form of economic self-sufficiency that gave rise to beloved theaters, grocery stores, barbershops, banks, churches, medical practices, hotels, and other dynamic businesses.

The segregated neighborhood’s rapid growth as a haven for African Americans, aided by the efforts of the wealthy Black landowner and investor O.W. Gurley, allowed money to circulate freely within the community. Locals purchased property and grew families. Greenwood became known nationwide as ‘Black Wall Street,’ serving as both a beacon and a model for how African-American communities might thrive in spite of every political, social, and economic effort to stunt their progress in the United States.

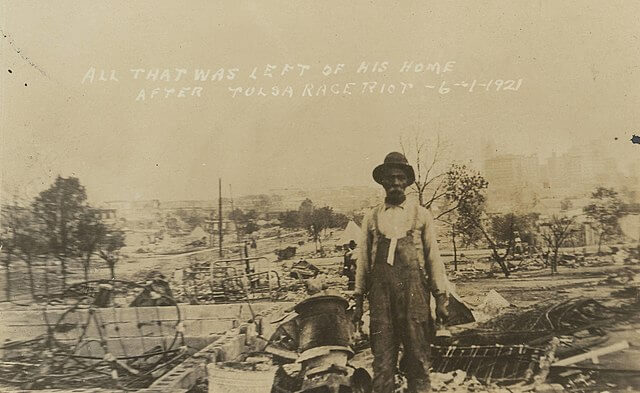

For two days between May 31 and June 1, 1921, however, Greenwood’s years-long evolution as a relatively safe haven for Black Americans came to an abrupt and vicious end. White mobs, fueled by dubious claims of aggression against a young African-American man and unchecked racial animus towards a community that had fostered its own prosperity, burned Black Wall Street to the ground.

They ransacked businesses, set fire to churches, raided homes, and murdered as many as 300 men, women, and children. Attackers, many of them deputized and armed by local government officials, stormed the neighborhood’s streets on foot and dropped turpentine bombs from crop duster planes. By the end of June 1, around 10,000 Greenwood residents had lost their homes and their livelihoods.

For many of the last one hundred years, the Tulsa Race Massacre was deliberately erased from the city and nation’s collective memory. The horrific attack was almost never memorialized or commemorated in any official capacity, and most state-approved textbooks simply glossed over the history of Greenwood. When they were acknowledged, the appalling events of 1921 were often characterized as a ‘race riot,’ an incident with perpetrators on both sides. With their community splintered, traumatized, and almost entirely displaced, many Black Tulsans refused to tell the true story publicly for fear of reprisal.

It was not until 1996, on the 75th anniversary of the atrocity, that Oklahoma established a commission to investigate the full history of the massacre. Five years later, the state approved new investments in Greenwood and announced plans for a small memorial in the area. In 2018, the commission was refashioned as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, raising a total of $30 million for additional investments, including $20 million for a museum commemorating the neighborhood’s history before, during, and after the massacre. The institution, now known as the Greenwood Rising Historical Center or Greenwood Rising for short, was planned for completion by the 100th anniversary of one of the most destructive single instances of racial violence in United States history.

Last month, shortly after the massacre’s centennial, Greenwood Rising opened its doors to survivors and their descendants. Families were welcomed to the brand new building, designed by Tulsa-based firm Selser Schaefer Architects, for a four-day preview of interactive displays curated and assembled by the New York-based exhibition experience firm Local Projects. The museum closed again from June 12 until its public grand opening earlier this month.

While many visitors, patrons, and officials have praised Greenwood Rising as a necessary, if late, commemoration of Tulsa’s darkest hour, the project has also received considerable criticism on the basis of both process and principle. State Representative Regina Goodwin, whose district includes much of Greenwood, told Tulsa World that she resigned her position on the Centennial Commission because of disagreements over whether funding for a commemorative center should go to the existing Greenwood Cultural Center or towards a brand new institution, as it ultimately did: “It is no secret that folks were saying that these monies were going to go to the Greenwood Cultural Center. I…was not participating because I thought there was an issue of integrity, and I think it has proven to be so.”

Other detractors, including some survivors and their families, have accused the Centennial Commission of window dressing, contending that the museum represents nothing more than a hollow, symbolic gesture towards people who need concrete change, including in the form of financial reparations. Among families whose rare chance at generational wealth was violently disrupted by the massacre, many argue that a portion (if not all) of the millions of dollars raised for the project should have been siphoned to direct compensation for victims and their descendants.

The call for reparations rather than a museum has been echoed by some local Black leaders, who voiced criticism of the city’s attempts to cover up its own ongoing issues with racism, systemic and otherwise. Tulsa city councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper, the only African-American elected official in the city government, joined Kristi Williams, the chairwoman of the Greater Tulsa Area African-American Affairs Commission, in refusing to support or visit the new museum.

According to Tulsa World, Hall-Harper derided Greenwood Rising as “a farce to make Tulsa appear not to be the racist-ass city that it is as we approach the centennial. That is all it is.” Williams, meanwhile, argued that Black Tulsans should follow in the footsteps of their ancestors and build an economy that works for the benefit of local African-Americans: “We cannot be complicit with white supremacy…That is what they left us with, and we have gotten away from that.”

As the city grapples with a history it has hardly confronted, debates surrounding the new museum are seemingly microcosmic of much broader national issues. With the United States Congress recognizing Juneteenth as a federal holiday for the first time this year, many Americans have highlighted the nation’s proclivity for symbolism over accountability and change. Even as the Tulsa Race Massacre slowly seeps into mainstream historical knowledge, most notably through its depiction in the 2019 hit HBO series Watchmen, there have been no successful attempts to provide significant relief to affected families. In May of this year, survivors Viola Fletcher (107 years old), Hughes Van Ellis (100 years old), and Lessie Randle (106 years old) offered impassioned testimonies in favor of reparations before Congress, but nothing has come of it.

Defenders of Greenwood Rising, which include a number of local African-American leaders who sit on the Centennial Commission, have pointed out that the museum has the potential to bring new revenue streams to Black-owned businesses in the area. The promise of more tourism has excited area business owners, including Angela Robinson and Willie Sells, both of whom insisted that the benefits accompanying the new institution will outweigh the costs. In a conversation with Tulsa World, Juandalyn Bailey characterized the grand opening as a chance to tell a story long silenced: “We have been too quiet about it for 100 years, but now we have something that is concrete that will let us see, but not only us, but my children and my children’s children.”

Even as Greenwood Rising opens to the public, though, Oklahoma’s state government continues to pass legislation that protects motorists who injure or kill protesters, criminalizes the obstruction of roads in the aftermath of last summer’s protests against police brutality, and prohibits certain teachings about race in public schools, the latter of which prompted leaders to remove Governor Kevin Stitt from his post on the Centennial Commission.

Many Tulsans agree that the museum offers an important first step towards reconciliation, but as with racial reckonings anywhere in the United States, the question remains: what next?