It’s fitting that the first survey of Helmut Jahn’s very long, very productive career should open in Chicago. After all, it’s where the German architect built some of his finest projects, the James R. Thompson Center foremost among them. Though his namesake architectural practice kept an office in the Loop, Jahn had long settled in the city’s western suburbs, where in early May, he was killed at a Campton Hills traffic intersection while riding his bicycle. He was 81.

“The day after the accident we sat down and said, ‘we should really do some sort of tribute,’ and by Monday we had a team,” said Michael Wood, senior curator at the Chicago Architecture Center (CAC). Helmut Jahn: Life + Architecture is the result of that conversation. The exhibit assembles scale models, photographs, and detailed timelines of Jahn’s work in the center’s second-floor gallery, where they will remain until October 31. Soon, the materials will be supplemented by proposals that seek to find creative uses for the Thompson Center, which is being threatened with demolition. (The designs will be shortlisted from a competition co-sponsored by the Chicago Architecture Club.)

Both vital and timely, the CAC show offers the local design community an opportunity to examine Jahn’s output in all its scope, style, and, yes, strangeness. It’s a career full of twists and turns. A drop-out from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Jahn worked his way up to the top of C.F. Murphy Associates. Inheriting the firm from founder Charles Murphy, he managed to steer it away from the patronage of Chicago City Hall and the nepotism that characterized Mayor Richard J. Daley’s rule in the 1970s. By the early 1980s, Jahn had put his name on the door (Murphy/Jahn) and cultivated a celebrity persona that helped bring in business. His buildings stayed ahead of the trends even as he aged into his late phase. Maintaining the nerve of his younger self, Jahn ventured further and further from Chicago in the new millennium. Projects like the Doha Convention Center in Doha, Qatar, and the Tokyo Station Yaesu Redevelopment couldn’t be executed by an architect intent on preserving a legacy.

Rebranded as JAHN, his office hit its stride in the 2010s as it pushed to integrate performance with environmental efficiency. Life + Architecture brings this under-appreciated work to the fore. Particularly effective is an oversized photo of the ThyssenKrupp Test Tower (2018) in Rottweil, Germany, in which the delicately articulated structure (designed to test high-speed elevators) looms over the medieval rooflines and turrets characteristic of the region, a mere 200 miles from Jahn’s birthplace in Nuremberg, Germany. Models provided by JAHN also betray the thoughtful posture of projects like the Joe and Rika Mansueto Library and the South Campus Chiller Plant at the University of Chicago, which diversified the classically oriented campus architecture without detracting from it. But Jahn was more often brazen: Designing a new student dormitory at his would-be alma mater, he paid little heed to the chilly principles of Mies van der Rohe’s modernist campus. Linear in form, the State Street Village barrels right through the school grounds, not unlike the Chicago Transit Authorities’ Green Line train that runs parallel to it. Though small, the exhibit allows one to see the commonalities that stretch across Jahn’s portfolio. Many of the buildings on display have a communal area or public space. The ThyssenKrupp Test Tower has an observation deck, and the Thompson Center in Chicago and the Sony Center in Berlin are famed for their generous atriums. The democratization of space could be considered a hallmark of Jahn’s designs, which should endear them to the public.

In 2018, CAC moved from its longtime headquarters on South Michigan Avenue to its current, much more prominent North Michigan Avenue location to better capture the attention of tourists strolling on the Magnificent Mile. In addition to its popular walking and boat tours, the institution invests a lot in original programming aimed at professionals and nonprofessionals alike; for instance, Building Tall, CAC’s display of giant scale models of global skyscrapers, is a perennial draw. Curiously, Life + Architecture is staged among these towerlets. Logistics and the short timeline may not have allowed the large models to be moved out, but their presence will only confuse casual visitors, who, observing the comprehensive timeline of Jahn’s work mounted next to César Pelli’s Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, might wonder, “Did Jahn design that?”

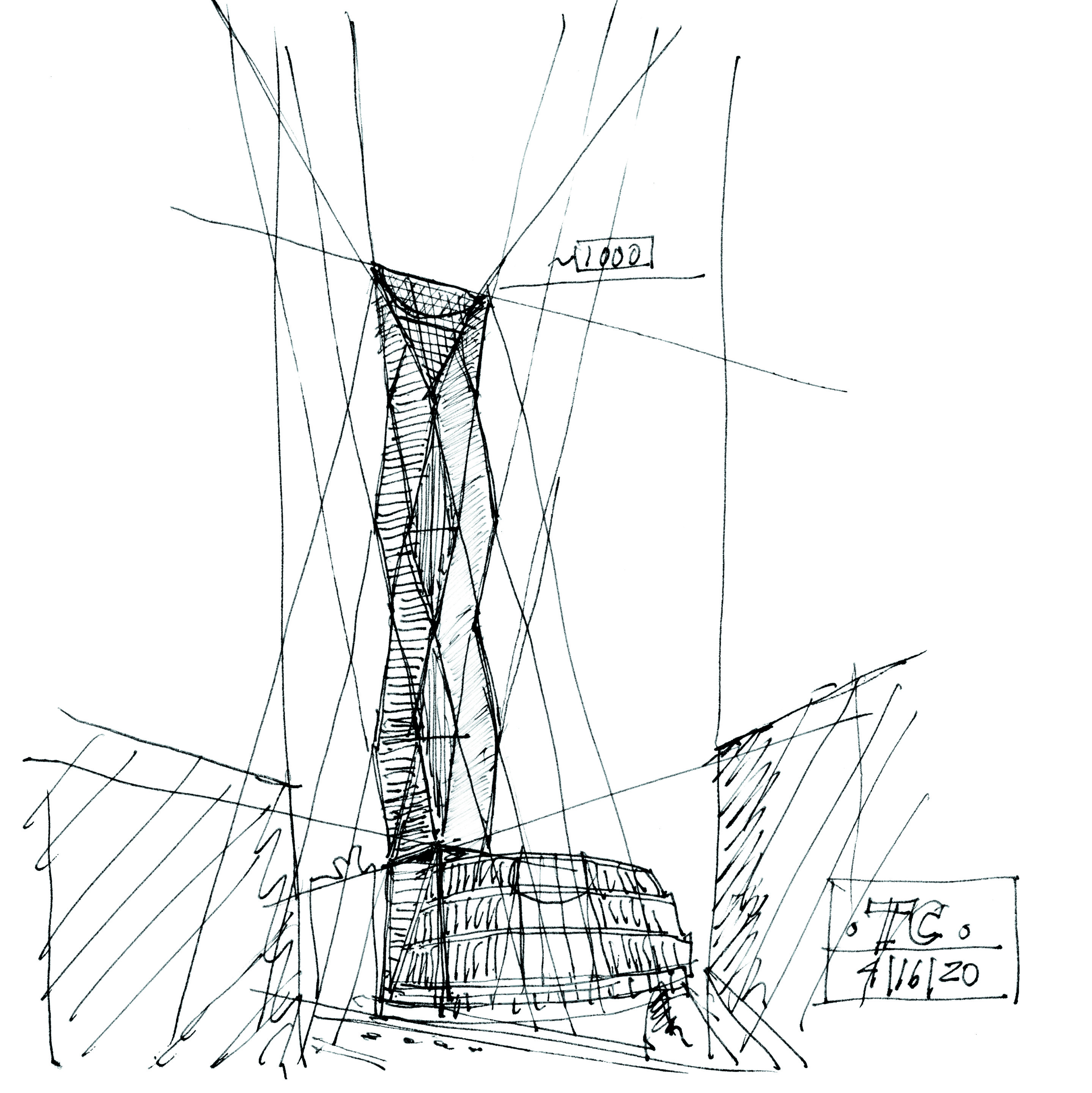

Chicagoans would likely have heard of Jahn just days before his much-publicized death, when the state finally made good on repeated threats to put the James R. Thompson Center (opened in 1985 as the State of Illinois Center) up for sale. Since then, the building—a unique example of Postmodernism in Chicago—has been nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, with local landmarking on the horizon. While the CAC exhibit doesn’t touch on these efforts, it doesn’t set them back either, and instead emphasizes the project’s ambition to foster a new kind of civic space. It is unclear how the results of the Thompson Center design competition will engage with the exhibit, or how useful the speculative ideas may be in saving the building. Jahn himself created two separate adaptive re-use plans for the Thompson Center, and both are on display. One commissioned by Landmarks Illinois in 2018 would install a 110-story supertall tower at the building’s southwest corner. Another, named “Thompson Center: Inside Out,” produced in 2020, proposed that the atrium be opened to the elements, thus expanding the center’s public footprint, and the building’s hours be extended beyond the rigid 9-to-5 schedule mandated by the state. It is difficult to imagine that other plans could top Jahn’s own, not least the harebrained reuse schemes for waterslide parks and multi-story cannabis dispensaries that have been floated on Twitter.

This isn’t to suggest that Jahn lacked a sense of humor. He could be quite witty and playful, enthusiastic and swaggering. These qualities are best captured in his musings on his work or the state of architecture, or even when he spoke casually to the press. His drawing, too, is the stuff of legends (Stanley Tigerman famously said he had “hot hands”). Unfortunately, this material is lacking in the CAC exhibit, whose organizers mostly limited themselves to the bare facts. This is a greatest hits collection, and time, scholarship, and further advocacy work are needed to compile a proper anthology.

Nonetheless, there are hints of the real Jahn here and there. Personal photos capture him at leisure, either manning the Flash Gordon, his sailboat, or running along the lakefront in flowing Bee Gees–era hair. The only architect to ever grace the cover of GQ, Jahn easily distinguished himself from his peers, who sometimes dismissed him as flashy or histrionic. Even as his reputation for refined buildings and spaces grew, he never seemed able to shake the style-over-substance stereotype. He did, however, know how to change with the times. We know the 1980s man, outfitted in a gangsterlike three-button suit and wide-brimmed hat, but Life + Architecture also shows us later Helmuts: standing closely by his wife Deborah, his movie-star face framed by wire-rimmed, rounded sunglasses that scream the 1990s or dressed in crisp white dress shirts and tailored jackets popular in the early 2000s. This commitment to style is especially poignant in a photo of Jahn from just this year. Captioned “in his office, 2021,” a masked Jahn sports a leather motorcycle jacket, fingerless gloves, and Balenciagas. He’s carrying a messenger bag like he has just arrived, ready to draw up something new and of-the-moment.

Elizabeth Blasius is an architectural historian and founder of Preservation Futures. She is the former Midwest editor for The Architect’s Newspaper.