In 1896, when Athens staged the first modern edition of the Olympics, fewer than 300 athletes from 12 nations descended on the Greek capital to compete in wrestling, fencing, gymnastics, and the world’s first marathon. The 125 years since that historic April have allowed plenty of time for dizzying growth in the scale and complexity of the games, which have now spanned 46 different host cities on five continents. During the recently completed two-week event this summer, Tokyo welcomed 12,000 athletes from 206 nations and territories to compete in upwards of 38 different sports—a colossal undertaking delayed for one year by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Today, cities hosting the Olympic games are generally expected to shell out enormous sums of cash, not only to construct large-capacity stadiums and world-class athletic facilities, but also on vast accommodations for team and media personnel, elaborate security apparatuses, marketing campaigns, and intricate infrastructure systems to support the influx of athletes, support staff, media crews, and spectators from across the world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the environmental impact of each set of games is typically enormous.

For the 2020 Summer Olympics, organizers took steps with the goal of making the games the most sustainable in modern history, including through the collection of 4.38 million tonnes worth of carbon credits to offset emissions generated over the course of the event. According to Masako Konishi of the World Wildlife Fund Japan, who sat on the sustainability committee for the Tokyo Olympics, the credits are worth about 150 percent of the total carbon emissions for the games, rendering them virtually carbon negative.

The carbon credit system, though, has been roundly criticized by climate scientists and environmental activists for generating a false sense of accomplishment and security. Industries that have used the market system to offset negative environmental impacts have done little, if anything, to actually reduce emissions through more radical operational adjustments. The progress made by such programs is, by most measures, far slower than the pace of change needed to mitigate the effects of climate change.

There is also a critical discrepancy between decarbonization efforts that reduce the amount of carbon emitted into the atmosphere in the future and decarbonization efforts that physically remove already-emitted carbon from the air, often through soil carbon sequestration or direct air capture systems. The Tokyo Olympics made use of the former, relying on sustainability projects in the Saitama Prefecture and the Tokyo metropolitan area.

Beyond Tokyo’s purchase of carbon credits, media coverage of various recycled or otherwise environmentally-friendly features at this year’s summer games was rife. Organizers arranged for electric transport vehicles to move athletes around the Olympic village, while cardboard bed frames and medal podiums 3D printed with recycled materials aimed to reduce waste. The medals awarded to top performers were crafted from upcycled smartphones, while Team U.S.A. entered the opening ceremony wearing belts made of recycled plastic bottles. The extra energy from the city’s grid required to power the games was reportedly powered entirely by renewable sources, and it is also certain that the prohibition of international spectators considerably reduced travel-related emissions tied to the event.

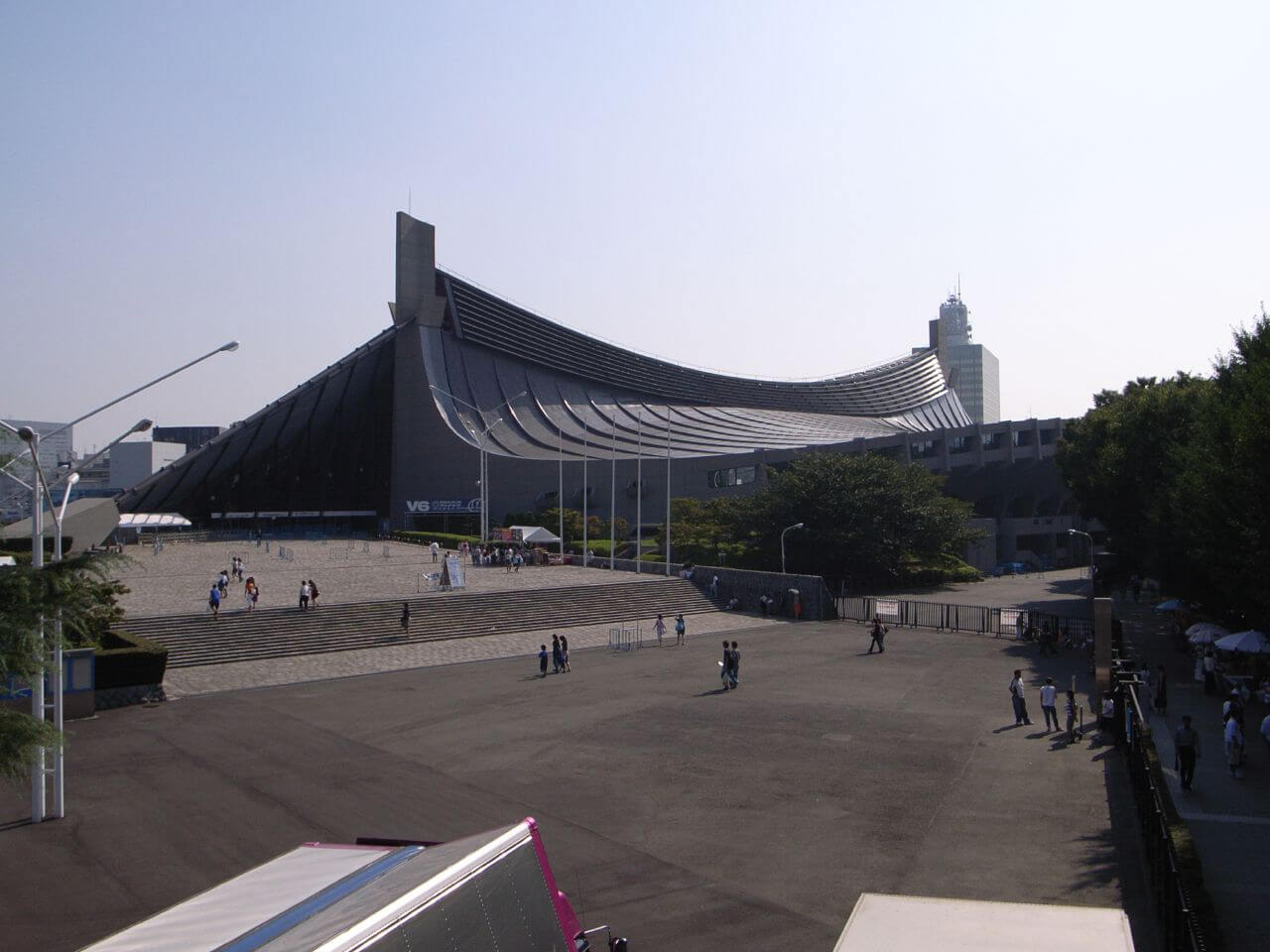

In the realm of construction, Tokyo 2020 was relatively reserved when compared to other recent Olympic games. Only about 20 percent of the venues had to be built from scratch, while the majority of events took place in existing stadiums or arenas, many of which were retrofitted to operate more sustainably. Kengo Kuma’s design for the centerpiece National Stadium relied heavily on timber, seen as a more environmentally-friendly material than steel. But according to NPR, the Rainforest Action Network has reported that much of the plywood in the stadium was sourced from rainforests in Indonesia that have since been replaced by ecologically destructive palm oil plantations. It is not clear that Olympic organizers factored the stadium’s ties to deforestation in its sustainability analysis.

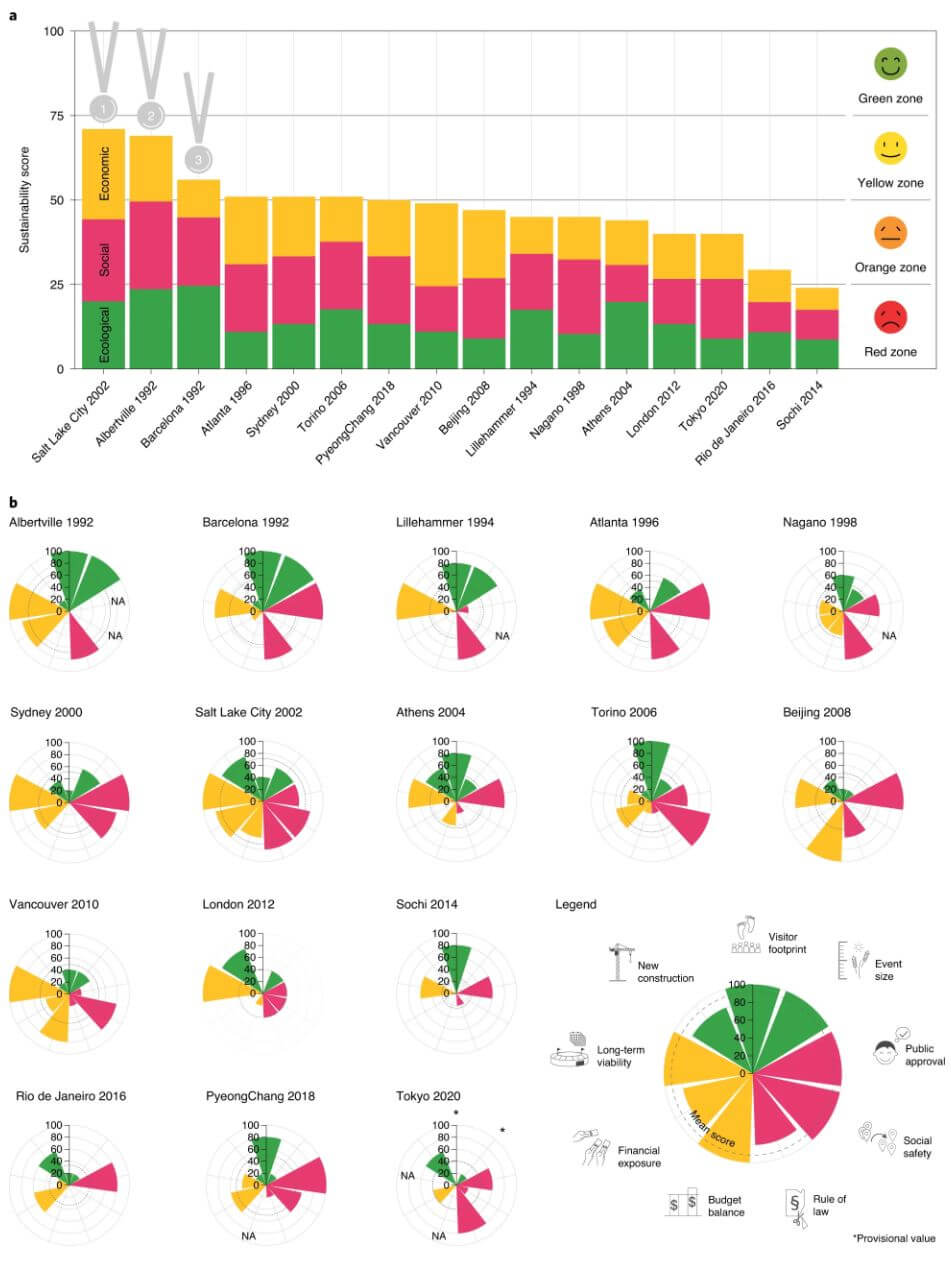

Some observers have raised even greater doubts about the sustainability prospects for the Tokyo games. According to a report conducted late last year by researchers at the University of Lausanne, Tokyo could in fact be among the least sustainable Olympic games in recent memory. The report measures every Olympics since the 1992 Barcelona summer games and Albertville winter games, considering a range of economic, ecological, and social factors. Events earn credit for balancing budgets, reducing financial exposure, increasing the long-term viability of venues, minimizing new construction and event size, preventing displacement, sticking to the rule of law, and maintaining high public approval.

Because the games were delayed by one year due to the pandemic, the researchers have not obtained data on long-term viability and budget balances for the Tokyo Games, though available indicators suggest that the event scored low in event size and social safety (largely due to the displacement of 500 people for the new construction portions). It is unclear whether higher scores in the “rule of law” and “new construction” categories will be enough to offset the less promising results.

The only Olympic games to rank below Tokyo so far are the 2014 Sochi winter games and the 2016 Rio summer games, both of which were notorious for far exceeding budget estimates and forcing the displacement of entire communities. The results of Tokyo’s sustainability initiatives may eventually push it into better company, though it seems impossible that the games will rank among the most sustainable—that includes Salt Lake City’s 2002 winter games, Albertville’s 1992 winter games, and Barcelona’s 1992 summer games.

The report suggests, however, that many of the more visible environmental actions taken by Tokyo Olympics’ organizers, including recycled podiums and medals, are effectively negligible in the grand scheme of things. The report gets at issues that climate activists have been raising for decades, including the idea that ‘development’ through new construction and the staging of massive global events, regardless of how many cardboard beds are involved, is an essentially unsustainable concept. As many have argued for the last several years, there may be a need for fundamental shifts in how the Olympics are conducted, including a move away from the host city bidding system.

Asking cities around the world to spend millions of dollars on marketing and promotional campaigns to host the event, then asking that they spend billions to construct new infrastructure and venues, is a grossly unsustainable model. Recommendations from critics include holding the games in the same four cities on a rotational basis or, on the even more ecologically conscious end, bringing them back to Athens permanently.

Given that the International Olympic Committee has selected almost all of its host cities through 2032 (a summer event that was just handed to Brisbane, Australia), it is unclear whether such a change will occur anytime soon.