Described by a local artist and neighbor as “a bouquet of flowers on the kitchen island” of the proverbial neighborhood, a novel new project has anchored down in North Texas. Portland, Oregon-based artist and designer Volkan Alkanoglu has recently completed a new pedestrian bridge and public artwork, titled Drift, in the South Hills neighborhood of Fort Worth, Texas. Part of the Fort Worth Public Art Program, the 62-foot-long bridge spans an existing dry creek bed which bisects a neighborhood characterized by modest postwar ranch homes. The piece creates a vital human-scaled connection over a creek that previously offered no clear way to cross for seven blocks.

Built for a relatively modest budget of $375,000, Drift exemplifies what Alkanoglu refers to as “plug-and-play” urbanism, or utilizing prefabrication to more efficiently construct elements off-site which can then be installed in their permanent locations quickly; Drift was trucked to Fort Worth and placed in a matter of hours despite being fabricated in Indiana. In keeping with the tradition of prefabricated, tightly controlled objects, Drift was inspired by precedents of divergent scales: both the splint design from midcentury architects and designers Charles and Ray Eames and the construction process of shipbuilding. The structure of the bridge also pulls from the tradition of shipbuilding, as a series of steel substructure contours create the skeleton of the final form. The result is a canoe-like hull, a smooth and continuous surface clad in timber slats, complete with a central “rudder” along the bottom edge of the midspan.

While the organic form and warm timber tones may have been inspired by mid-20th-century design, the result is a product of contemporary digital tools. “We used a series of digital and algorithmic software to design the bridge, including the steel substructure and the timber planks,” says Alkanoglu. “Each piece of the bridge is unique and custom fabricated.”

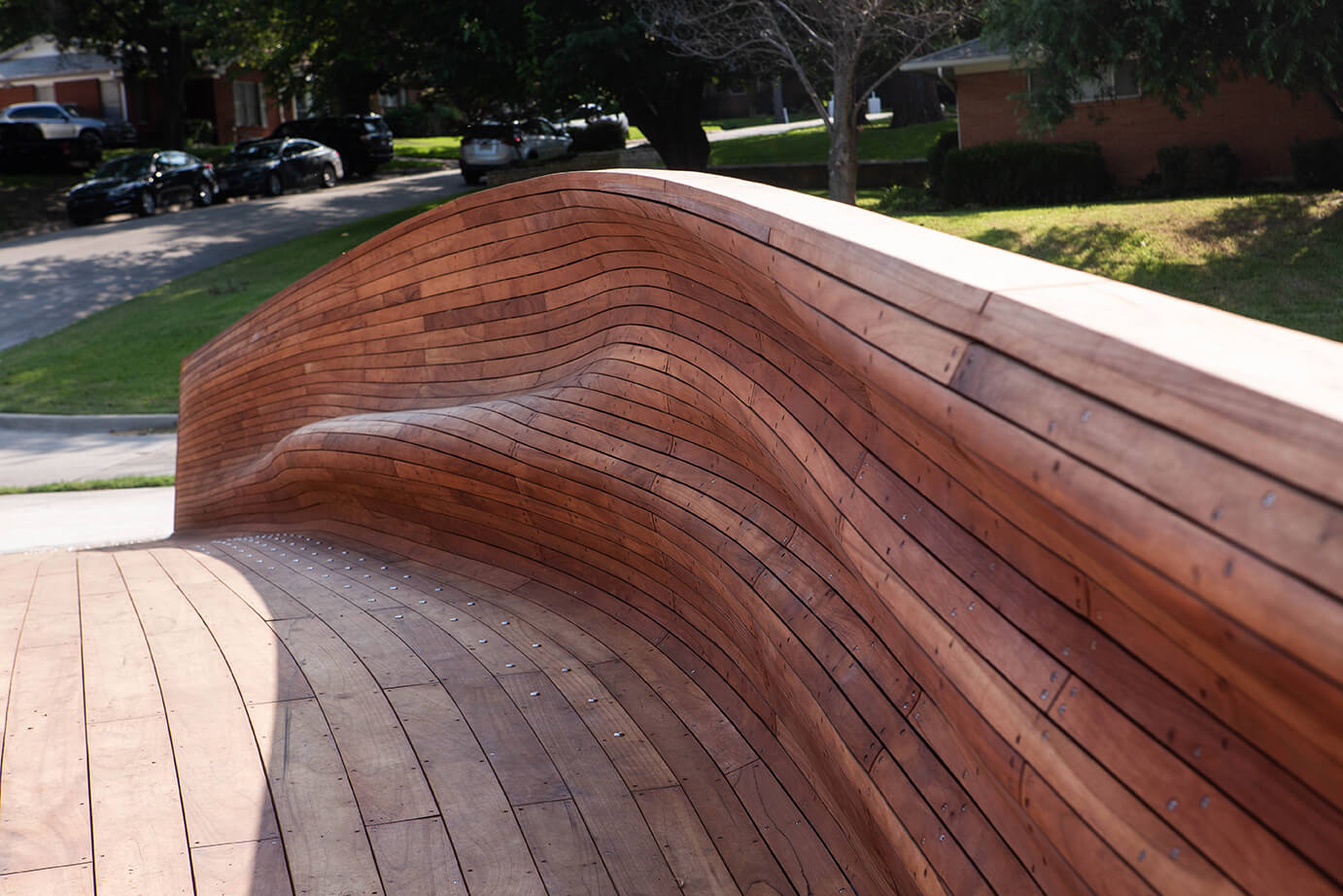

Those details of the bridge reveal a level of complexity and elegance that would’ve seemed impossible in the Eames’s molded plywood experiments of the 1940s. To achieve the double-curvature of the form, the timber cladding was flip-milled on a CNC machine and a number of the slats in particularly high curvature zones were steam-bent for greater pliability. Additionally, the width of the slats varies and gradates across the surface of the piece; slats flow from wide to thin, from anchor point to midspan, switching from thin to wide above and below the defining curved crease along the exterior of the hull, then again from wide to thin as the slats transition from the exterior surface to the interior of the bridge. There is constant movement and variety upon closer inspection, despite a monolithic first-impression.

The interior of the bridge is also an unexpected moment of delight; while the overall form of the bridge is smooth and elegant, the curves remain quite gradual and tame. Yet, for the occupiable section of the bridge, Alkanoglu sought to create a work that was not simply a vehicle between two points but could also function as a destination of its own. The geometry of the bridge transitions into a freeform, wildly undulating surface that facilitates benches and areas of respite, offering perspectives of the greenway previously unseen and intimate moments to interact with neighbors in a public space.

The aesthetic qualities of the bridge were a major part of the design process and the result the public now gets to enjoy, but appearance was far from the only consideration in the computational design process. Alkanoglu describes this process and the considerations for iteration: size, volume, cost, context, structure, and material specifications. Perhaps most importantly with the prefabrication process, “we also had to consider the size of the truck and weight limits since this bridge was fabricated off-site in Indiana and delivered by truck to Texas.” While so-called “parametric design” has been something of a buzzword for years now, Alkanoglu still sees its promise for works like Drift: “our digital design process allows us not just to connect the dots but to create a feedback loop to adjust to insights [and] parameters while rapidly iterating and testing ideas. There is a paradigm shift where the role of the designer changes from the single author creating one proposal to being more of an editor or curator who can select and choose from a series of options.” Parametric design may not be in vogue in architectural discourse anymore, but with continued development in technology, automation, and computational intelligence, Alkanoglu’s attitude of the designer-as-curator could still provide new and open ground for more inclusive and sustainable works of art and architecture.

Although Drift was commissioned by the Fort Worth Public Art Program and, as such, is presented as a work of art, it exists at the intersection of multiple typologies and scales. Art and architecture, of course, but also importantly, infrastructure and urbanism. While prefabrication has proved beneficial in the construction industry, from reducing labor and material costs to improving tolerances and workmanship (and scheduling is unaffected by weather), Drift offers a glimpse into how prefabrication could be used for works of an infrastructural scale.

Infrastructure consists of structures that allow for a smoothly functioning society, but the benefits of new and improved installments rarely feel worth the cost of “getting there.” Nearly everyone from idling interstate drivers in Waco, Texas, to MTA patrons in New York City, has a horror story of the inconveniences caused by “improvements” being made to their infrastructure-of-choice. Plug-and-play urbanism could offer the rewards of state-of-the-art infrastructure upgrades without the logistical nightmares of major construction in-situ, as most of the work can be done in warehouses and rights-of-way need only be closed off for an afternoon at a time for installation.

Although Drift’s development process may offer us a model for small-scale urbanism in the future, it remains most impactful now as a programmed piece of art. Alkanoglu recalled how “active and engaging” the local community was throughout the design process. After presenting the initial design concept to a gathering of over one hundred residents in a local church, the design team was “able to answer many questions and received a lot of appreciation.” Alkanoglu added that “We continue to get a lot of exciting positive responses by the local community now that the bridge is finally in place.”

Adding to the positive local response, the artist I encountered at the bridge when I visited described the importance of good art in unexpected places; what was once considered a ditch that divided the neighborhood can now be seen as a public green space, a park to be enjoyed which connects people. While objects in galleries hold value as something to be seen, to this artist—and to other residents of South Hills—art like Drift which can be inhabited and experienced, open, visible, and accessible to the public, is far more personal and meaningful.

Designer: Volkan Alkanoglu, Portland, Oregon

Client: City of Fort Worth, Fort Worth Public Art Program

Public Art Manager: Anne Allen

Fabrication: Ignition Arts LLC, Indianapolis, IN; Brownsmith Studios, Bloomington, Indiana

Structural Engineering: CMID Engineers, Indianapolis, Indiana

Geotechnical Engineering: Alpha Testing, Fort Worth, Texas

Material Testing: Simpson, Gumpertz & Heger Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts

Concept Engineering: AKT II, London, United Kingdom