His name is Bruce. The gregarious stuffed moose who looks about as real a Bullwinkle as you could find greets visitors at the Corvallis Museum in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and sets the tone for what’s to come. The new institution brings the collections of the Benton County Historical Society and Oregon State University under one roof, offering a bewildering array of objects: historical quilts and textiles, crockery and ceramics, Civil War–era paraphernalia, costumery of all sorts, commemorative coins, salvaged signage, antique dolls, rickety toy trains, and a vintage Erector set.

But the contents of this exceptional small museum, situated just one block from the banks of the Willamette River among historic storefront buildings in downtown Corvallis (population 60,000), are only half the story. The building, by Allied Works Architecture, is in line with the firm’s work for prominent art centers around the country, only here light-filled spaces and a Japanese-like reverence for natural materials are put in the service of a modest if charmingly eclectic collection.

Longtime Benton County Historical Society director Irene Zenev first became enamored with Allied Works after seeing pictures of the firm’s 2008 transformation of the midcentury Huntington Hartford building by architect Edward Durell Stone into New York’s Museum of Art and Design. “It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen,” she recalled. “And when I read that he”—Allied founder Brad Cloepfil—“had moved the elevator from the center of the building off to make the galleries more accessible, I thought, ‘This guy knows what he’s doing.’”

Cloepfil, who splits his time between the studio’s Portland, Oregon, base and New York outpost, readily accepted the commission. “We knew we had to do something simple and elegant within a modest budget,” he told AN, “but we tried to make it aspirational too.” The nature of the collection allowed for certain opportunities. Whereas paintings need to be shielded from daylight, ephemera can better stand up to the sun’s rays (within limits). And where fine art calls for restraint—a whitewashed neutrality that sometimes borders on inanity—memorabilia and folksy curios stand to gain from pluck and variety.

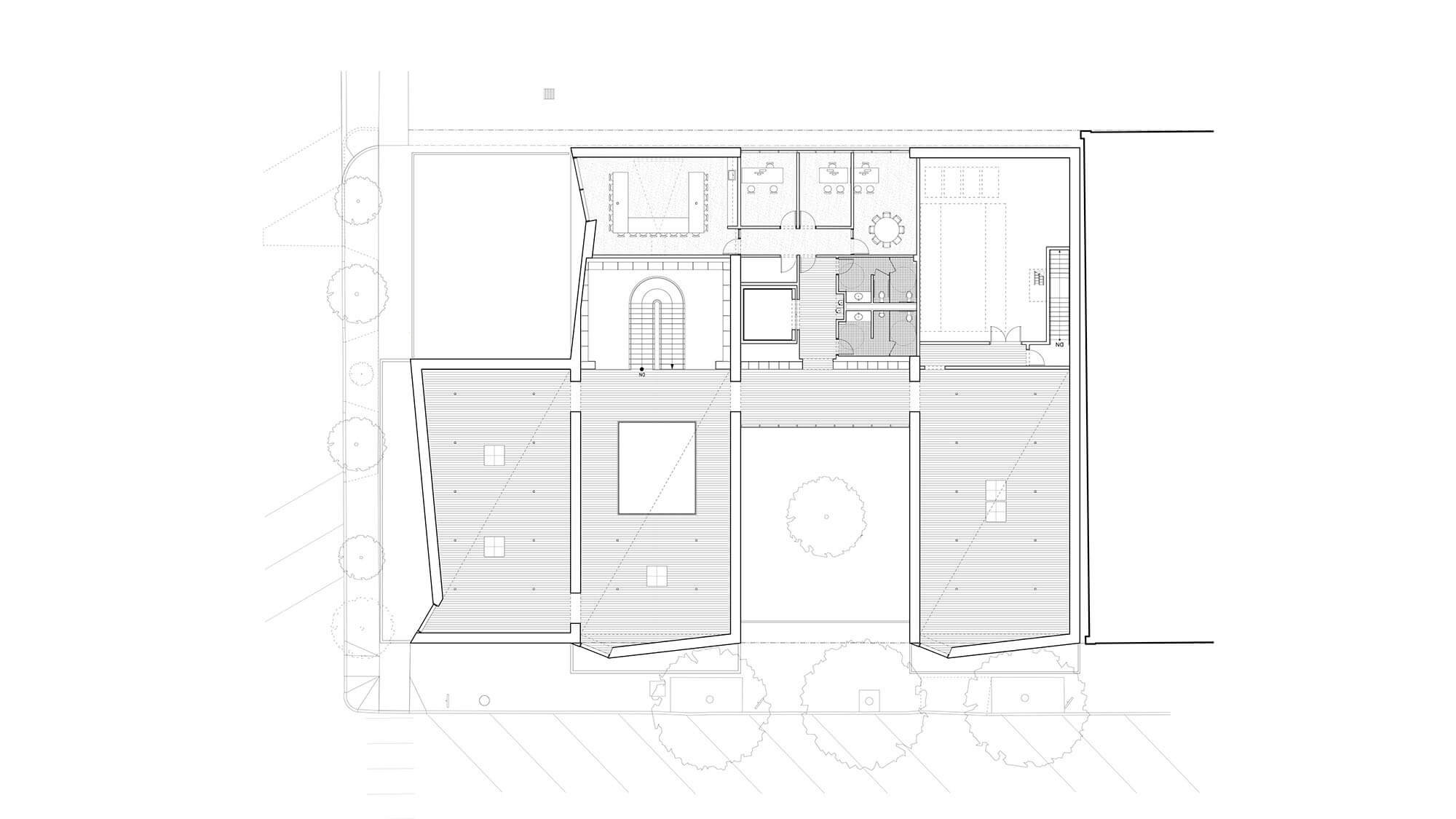

The 19,000-square-foot museum is wrapped in glazed ceramic tile, each piece hand-raked, which helps create varying arrays of reflection and shadow. Inside, the building is divided into four simple bays, with a small courtyard occupying the place of the third. The lobby and multipurpose event space, faced in glass, open onto the small but generous court, and from the event room the glass can slide away to create a hybrid indoor/outdoor space. Galleries are not sized for auras, but for people and objects, and full-size windows invite the street inside to a degree unthinkable for an art museum.

“I don’t think Allied Works could have done this ten years ago,” Cloepfil said. “The architecture [at Corvallis] was not compromised. It reflected a kind of discipline that we have now. We can conceive things that can be built economically but feel powerful.”

Perhaps the biggest surprise is how exhibit designer Renate brings the Benton County Historical Society’s collections alive yet also gives their eclecticism clarity. Historical photographs are mounted in frames that turn away from the walls on hinges, revealing text boxes behind them. Curators clearly had fun with juxtapositions, as in a “Hats and Chairs” room that is exactly that. Elsewhere, giant lumberjack saws sit beside vintage early computers, model train sets beside a human-goat suit used by an early nature photographer to clandestinely take pictures of mountain goats. The collection is presented with the simplicity and delight of a children’s museum, which only occasionally bumps up against the architecture.

“The demographic of Corvallis, while a college town, also has a large retired population and lots of families with children—that was top of mind as we did our design,” explained Renate principal Anne Bernard. “In this manner the museums we work on become multigenerational spaces and hence community spaces. We did this all within one material palette that complemented the Allied Works design so that the whole thing was fluid and had lots of interstitial moments.”

No wonder Bruce seems to be smiling. This could have been a strange union of world-class design and an overwhelming accretion of stuff, of urban museum and small town, interlopers and locals. That the Corvallis Museum largely avoids this outcome demonstrates that good architecture can take root anywhere. It just needs a little coaxing.

Brian Libby is an architecture and arts journalist, a podcast host, and a photographer-filmmaker based in Portland, Oregon.

Corvallis Museum

Architect: Allied Works Architecture

Exhibit designer: Renate

Location: Corvallis, Oregon

Builder: Gerding Builders

Civil and structural engineering: Devco

MEP/FP systems engineering: Glumac

Tile cladding: Design and Direct Source

Envelope consultant: Morrison Hershfield

Curtain wall system: Kawneer

Wall panel systems: Kingspan Insulated Panels

Acoustical wall paneling: Unika Vaev

Flooring: Castle Bespoke Uptown Collection – Mosaic

Gallery track lighting: LumeLEX