Noguchi: Useless Architecture

Noguchi Museum

Long Island City, Queens

Open through May 8, 2022

In 1962, Isamu Noguchi created Floor Frame, a minimalist bronze sculpture that appears to sink into the ground. It resurfaced in the public eye in late 2020, deep into the pandemic, when the Trump administration installed it in the White House Rose Garden. The piece is the first by an Asian-American artist in the White House Collection, and officials characterized its inclusion as a progressive achievement for the Asian American community. But many in the community were not swayed by the strained optics. Marci Kwon, codirector of the Cantor Arts Center’s Asian American Art Initiative, noted the “shameless hypocrisy” of using Noguchi, who died in 1988, to drum up good publicity for an administration widely criticized for stoking anti-Asian sentiment. Kwon didn’t mince words, calling out the act as “racist framing.”

In August, the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City, Queens, issued a call for the borough’s AAPI artists to design antiracism banners to adorn its exterior walls. The initiative mobilizes Noguchi’s Japanese heritage in a show of solidarity with those acting against “Asian hate.” For a figure known to break the boundaries of identity and artistic practice, it may seem that race is a frame he has not been able to escape.

Inside the Noguchi Museum, a new exhibition does not weigh in on these issues but instead aims to resituate the man in his own time. Noguchi: Useless Architecture opens on the second floor of the museum, whose tranquil interiors still hew closely to the artist’s original intentions for them. Spread across three galleries, the show has a relatively small footprint that can barely contain the ambition of curators Dakin Hart, Matthew Kirsch, and Kate Wiener. By narrowing their focus to Noguchi’s flirtations with architecture, they add a fresh dimension to a household name. Theirs is a different kind of framing.

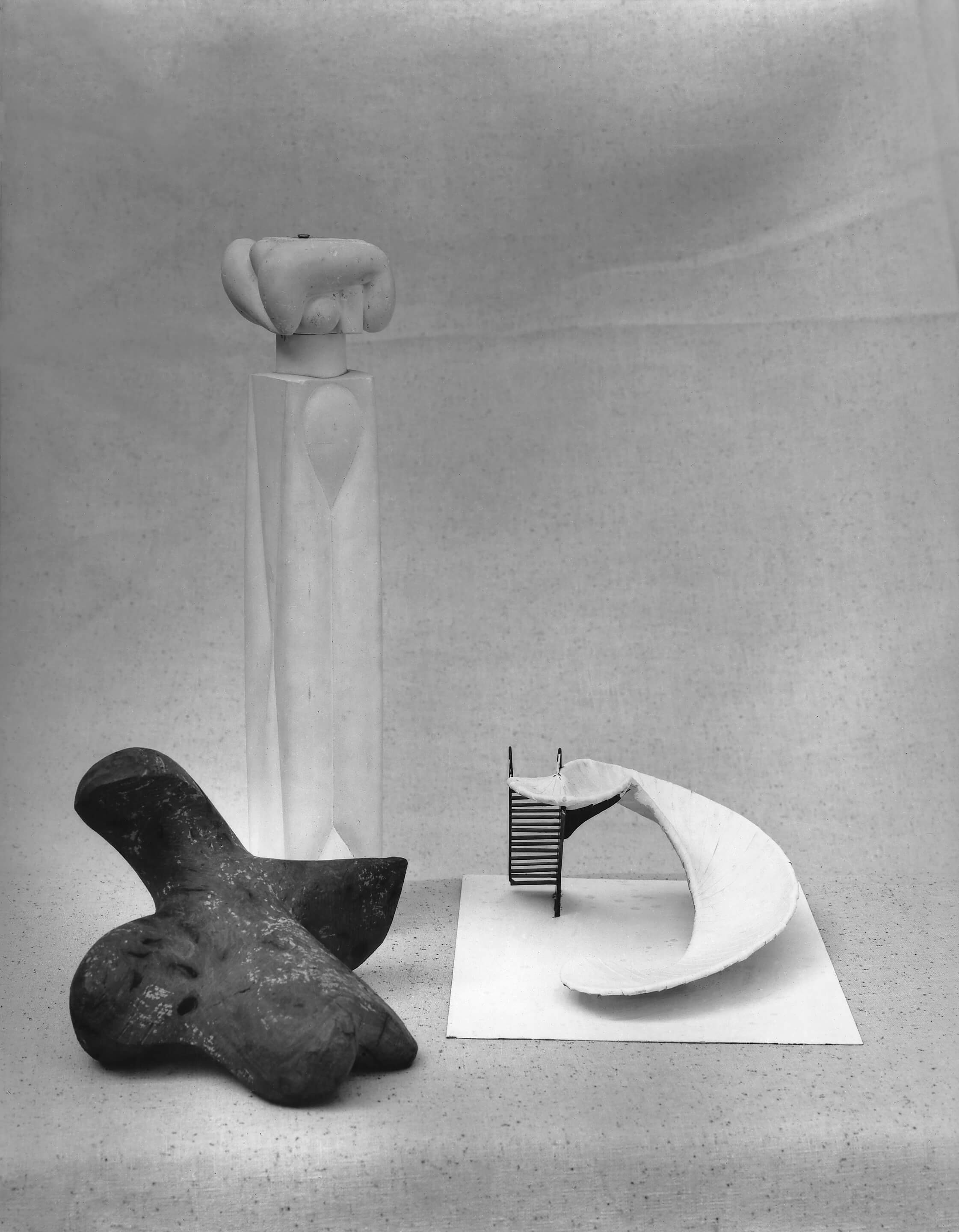

In the central gallery, tall columns instill something of the militant quiet of the classical Grecian orders. Swirling marble clouds mounted atop plain steel shafts replace the decorative capitals of yore. Noguchi completed Capital (1939) on the cusp of World War II, during a time suffused with anti-Japanese sentiment. Capital #2 followed in 1942, the same year he voluntarily entered an internment camp for Japanese Americans. Both the pseudo-architectural work and the racial prejudices that gave rise to it have survived, with the former memorializing endurance against repeated history.

Sculptures such as these bear all the sophistication of Noguchi’s idol and mentor Constantin Brancusi, only they emanate a more inviting glow. This affectionate warmth permeates the museum galleries, thanks to strategically placed Akari lanterns, which Noguchi designed in the early 1950s. In a restaging of Space of Akari and Stone, a 1985 display designed by the artist’s architect friend Arata Isozaki, the paper lamps appear like alien life-forms crash-landed onto foreign soil. Their bulbous bodies stand on little metal “feet” so that they seem to sit and squat, dither and dawdle—strangers navigating a strange land. Some wayfarers are jailed in steel cages.

By contrast, a gallery devoted to Noguchi’s playscapes promises freedom. Children carefully scaled a full-size replica of a terrace intended for the “Riverside Playground” (c. 1961, fabricated 2020), an unrealized collaboration with architect Louis Kahn for Riverside Park on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. A bronze model miniature is laid adjacently and offers a birds-eye perspective of the choreographed movement imbued in the composition’s layered triangular forms. (Noguchi drew inspiration for architectural terracing from Machu Picchu, the 15th-century Inca citadel located in present-day Peru.) Although the park project took years to plan, residents eventually called for its halt owing to failures to involve them in the process.

Noguchi most likely did not see these efforts as wasted, as impracticality appealed to him. The exhibition takes its title from his description of the Jantar Mantar, five royal astronomical observatories constructed in Jaipur, India, in the 18th century. Built to measure the movements of the moon, stars, and other cosmic bodies, these stone instruments have since deteriorated into obsolescence but still exude a sense of poetic mystery. From them, Noguchi derived the conclusion that “useless architecture” made for “useful sculpture.”

Shorn of its use, and separated from its social context by hundreds, if not thousands, of years, architecture could finally come into its own, as line and form. In this, antiquity offered the greatest lesson. Noguchi first began visiting Greece in the 1950s, having found a reliable marble dealer there, and soon “started a custom of stopping in Greece on my various trips to and from Japan,” he later wrote. His photographs of sacred temples and hillside amphitheaters in Athens and Delphi, in which eroding columns rise like totems and dilapidated marble appears whiter than white, reveal an optimism for what can be salvaged from social ruin.

One photograph shows his wife at the time, Yoshiko Yamaguchi, standing in front of the Erechtheion. Always attentive to performative staging, Noguchi frames her just below its famed caryatids; perhaps attempting to further the likeness to the stone women, outfitted in Phidian drapery, Yamaguchi wears a striped skirt and a loose shawl. The real-life muse is misidentified with an object and vice versa. It’s a theme that carries into midcareer pieces like Small Torso (1958–1962) and unfinished marble studies, whose dimpled and jagged edges betray a deep appreciation of human form. Although Noguchi found early commercial success in his realistic portrait busts, he preferred to dwell on the ambiguities of stone becoming flesh.

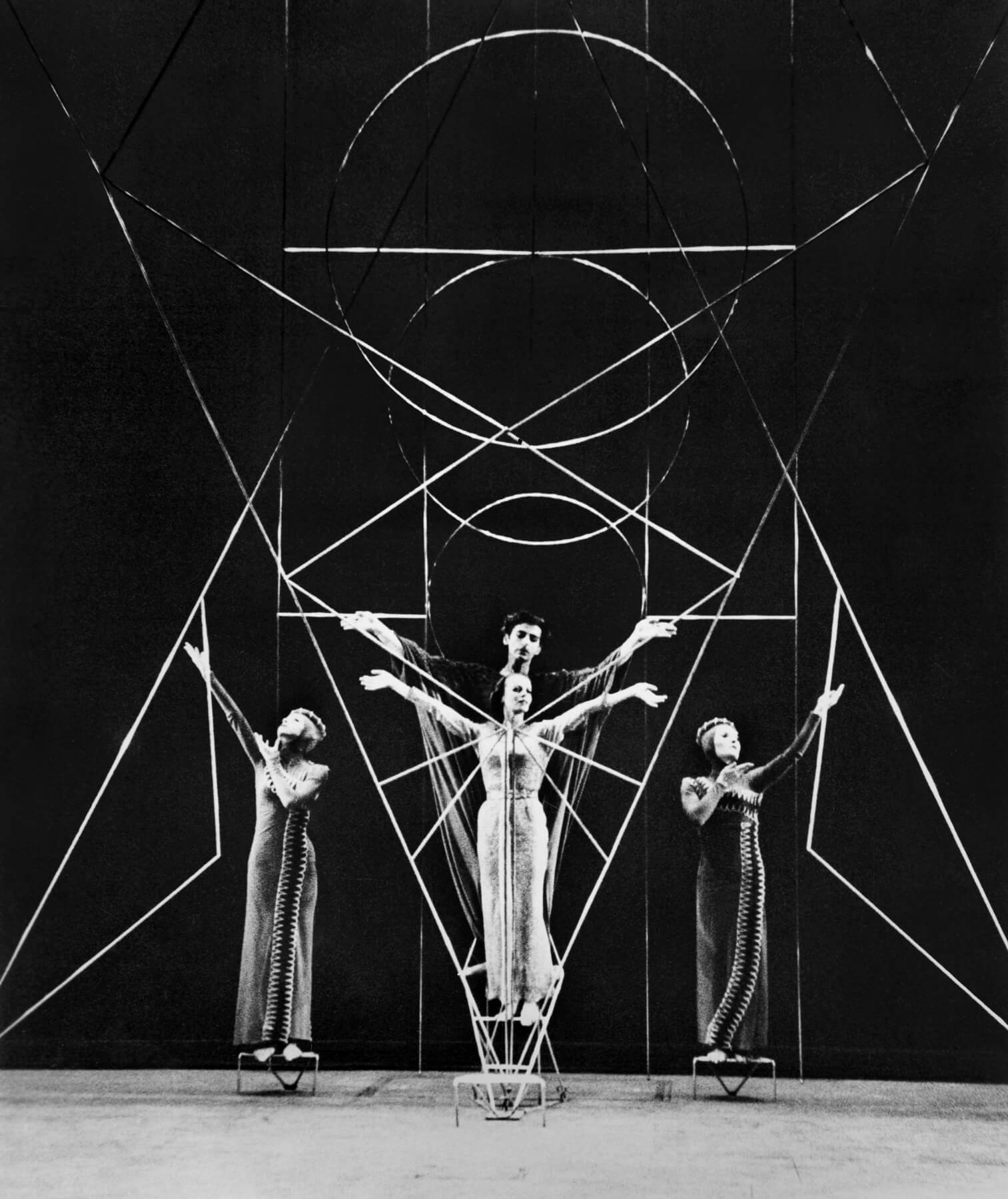

For Noguchi, sculpture was “useful” not in any purposeful sense, but rather as a means to stimulate thought. Whether it was stairs that led nowhere (Model for Slide Mantra, 1966) or heraldic scaffolding (set design for Seraphic Dialogue, 1955), a work was left for the viewer to complete. Nowhere is this more the case than in Noguchi’s ethereal theater set pieces. Though emptied of performers and deceptively simple in their construction, they retain their operatic aura. In his set design for Martha Graham’s ballet Frontier (1935), Noguchi placed a lone section of log fencing at stage center. Behind it, he attached a taut length of rope from stage to ceiling in the form of a V. In its original edition, this perspectival vector pointed behind and above audiences, effectively extending the stage past the limits of the theater.

Useless architecture, Noguchi observed, “contain[s] an appreciation of measured time and the shortness of life and the vastness of the universe”—to which can be added “the impermanence of empire.” In one of the exhibition’s more inspired gestures, the curators counterpose Noguchi’s photographs and studies of ancient ruins with small marble maquettes whose orderly, orthogonal geometries evoke metropolitan skylines. These, too, shall pass. What useful sculpture might they leave in their wake?

Danielle Wu is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, New York.