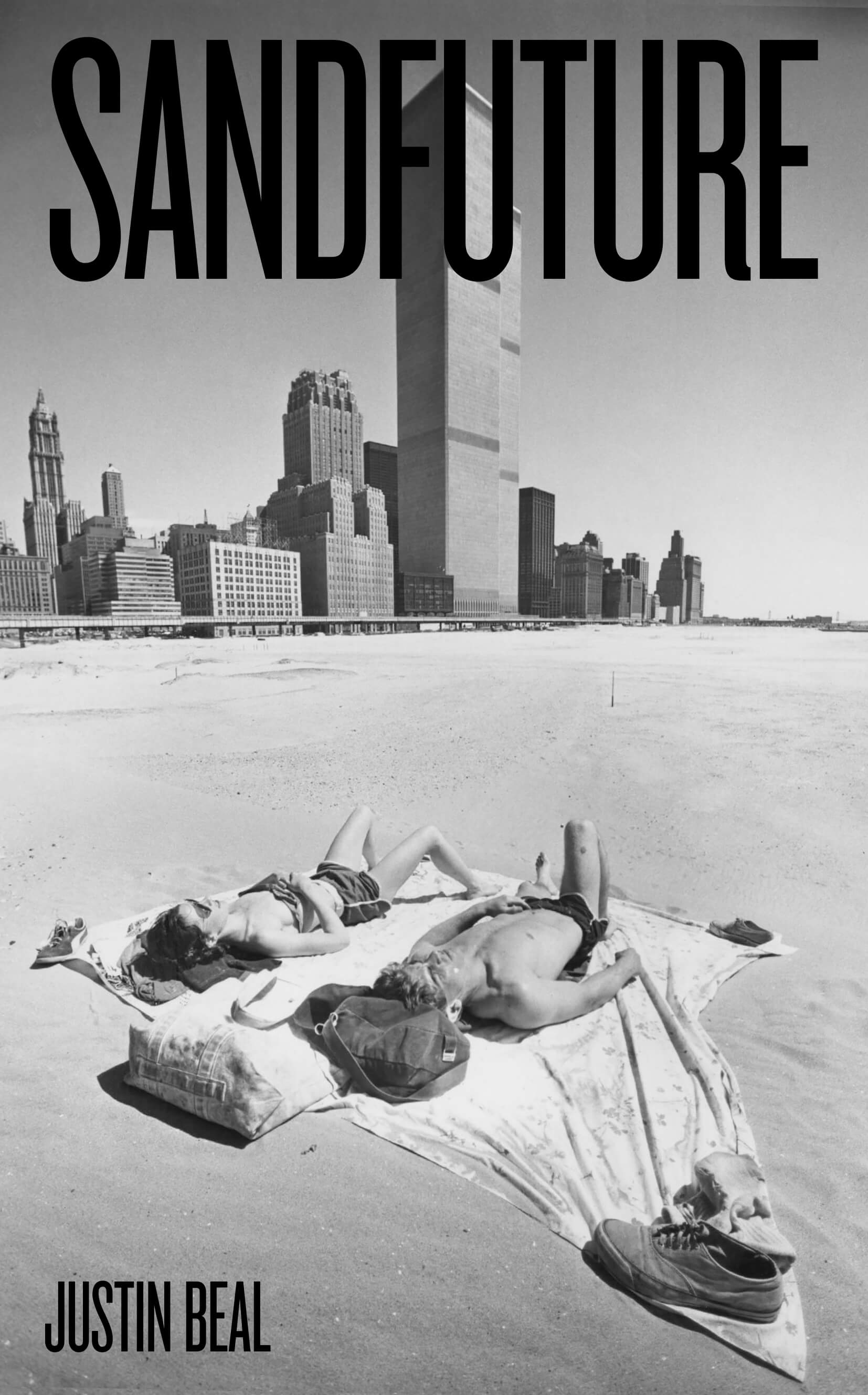

Sandfuture is ostensibly a book about the World Trade Center. This is what we can glean from the cover, which features Fred R. Conrad’s ravishing 1977 picture of sunbathers lying on a beach in front of the recently completed Twin Towers. The irony is deeply felt as this picture captures a moment of pristine elegance at odds with a city on the brink of financial ruin. The beach that became the setting for the image was a contrivance, a cenote of dredged sand that paused development on the site that would soon become Battery Park City. And yet the book’s title takes on a mysterious and elegiac aspect, as if that sandy spit on the western edge of the World Trade Center site were a vision of a future that never came to be, frozen in the amber of a bewitching photograph. There are no subtitles, no indicators of a higher agenda. In a field of architecture books that range from coffee-table doorstops to specialized scholarly monographs and obscurantist histories, Sandfuture appears mysterious, even fully formed. What is it? Why did Justin Beal, an artist, write this book?

With tousled hair and of rumpled sartorial bent, Beal appears affable and confident. His kilowatt smile is Dickie Greenleaf–vintage, right up there with the Doug Aitken and Tom Sachses of the world. And yet his work sits uneasily at the intersections of sculpture, industrial design, and architecture. Even the most cursory of glances at his wide-ranging works demonstrate a kind of frenzied connectivity among the design disciplines that would turn Rosalind Krauss’s famous 1979 diagram of “The Expanded Field” of sculpture into a pile of pickup sticks or I Ching reeds. His writing, especially the catalog essays for exhibitions such as SOFTMATTER (2015) and TOUCHPIECE (2017) is knowing. Still, Sandfuture is the first work of Beal’s that tackles architectural history’s canon directly. And it does so with the kind of brio and panache that seems absent from architectural writing these days.

Articulate and searching, Beal modulates between autobiography and architectural history fluidly and with authority. He begins with an epigram from Filarete’s Treatise on Architecture (1464). It is customary, ritualistic, an opportunity for Beal to shed his artistic mantle and announce his intention to be historical. And yet we learn how his interest in architecture was formed preternaturally as a seven-year-old. Travels with his grandfather in and out of Logan Airport in Boston helped him see Yamasaki’s Eastern Airlines Terminal in a different light, not as a building, but as something grander. It “was the first building I remember recognizing as architecture,” Beal writes. “It looked new in a way that buildings in Boston seldom did.” Like his grandfather, the terminal “seemed out of place in such a taciturn city.”

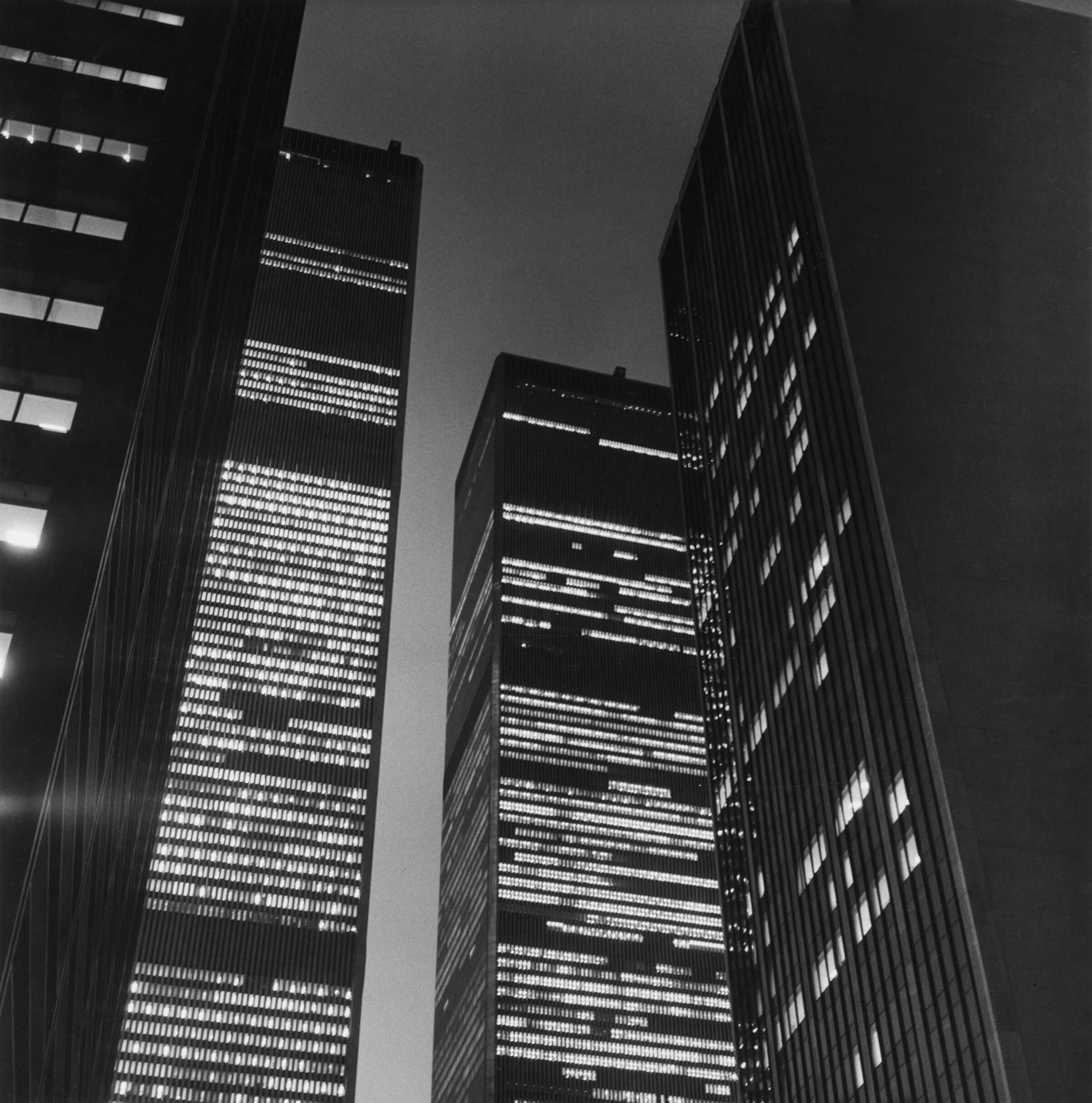

These are the kinds of moments that show how Sandfuture is a personal book. Beal takes criticism of Yamasaki’s work to heart, and his own examinations of the architect’s output, from the Reynolds Metals Regional Sales Office (1955–59) and onward, are not just deeply felt but solipsistic. In the book’s opening pages, he takes us to the base of the World Trade Center, and we are there with him looking upward and seeing the endless aluminum shafts reaching into the sky. “They were alpine—a pair of aluminum mountains,” Beal writes of the Twin Towers. “They induced vertigo. They exceeded haptic experience. They failed as buildings, but they were brilliant as objects.” He repeats this technique throughout Sandfuture. He leans on personal accounts of his career and encounters with architectural history to construct a version of Minoru Yamasaki that runs counter to the more familiar—and tragic—appraisals of his long and productive career.

Yamasaki had the dubious distinction of having two of his signature works destroyed on live television. The images of the (second) demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex on April 17, 1972, have been the source of continual debate about architectural modernism’s failures. The footage of the 9/11 attacks and the destruction of the World Trade Center is nothing short of collective trauma. Beal revisits familiar terrain about these buildings, from the acrimonious debates about interior circulation at Pruitt-Igoe to the eleventh-hour deals and legal peccadilloes that preceded the construction of the World Trade Center. Beal does not question their significance. Instead, he writes around detractors such as Ada Louise Huxtable, Vincent Scully, Martin Filler, and others, whose negative assessments of Yamasaki’s work typically focus on his flair for designing ornamental motifs or overscale buildings and lump him with the likes of Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, and Edward Durell Stone.

Beal wants to expand the narrative of Yamasaki’s life and work to account for the absence of an architect who once appeared on the cover of Time, had more AIA commendations than Eero Saarinen or Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and built 79 buildings during his career. And to do this, he becomes a kind of George Smiley, an artist hunkered down among piles of boxes at Cambridge Circus, looking for that paper trail that will confirm his gut instinct that Yamasaki was an architect who wanted his buildings to do good for everyone. In short, Beal becomes a historian of sorts. He surveys literature and visits archives—a necessary task that augments what little we know about Yamasaki’s work from the handful of articles he penned for various magazines and his overlooked self-critical autobiography, A Life in Architecture (first published in Japan in 1979 and edited to exclude Pruitt-Igoe and other works). Sandfuture is also a diligent biography as it builds on the material from A Life.

We come to know about the trials and tribulations of Yamasaki’s career, from his encounters with racism growing up in Seattle to his early stints working in the offices of Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and Harrison & Abramovitz; then Hellmuth, Yamasaki & Leinweber, a firm that eventually split in two to form Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum (later HOK); and finally, of course, Yamasaki & Associates. Unlike Dale Allen Gyure’s 2017 monograph Minoru Yamasaki: Humanist Architecture for a Modernist World, Sandfuture intentionally veers away from being comprehensive.

Instead, Beal accomplishes one of the greatest sleights of hand in recent architectural writing. He does more than just give a firsthand account of his own experiences with Yamasaki’s work. He places himself in the middle of this historical reckoning and exists as someone who is more than a witness or narrator. Perhaps he is like Ishmael, the narrator from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), who ends the novel with a testamentary act, quoting the book of Job (“And I only am escaped alone to tell thee”) and escaping the foundering remains of the whaleship Pequod, observes, “I was then, but slowly, drawn towards the closing vortex.” It is a description that will resonate with readers who remember the early morning of October 29, 2012, when Hurricane Sandy arrived in New York. We are with Beal as he shows us stormwaters flooding basements and art storage areas, a force majeure event that turns the chain of galleries below 27th Street into archipelagoes of detritus, small vortices of flotsam and jetsam that persist as everything else is washed away and scuttled along the surging undertow. These images locate Beal’s narrative within recent memory, and they are beguiling, even familiar. (Besides Melville, Robert Musil’s description of a “barometric low” that moves across Europe and settles over Vienna in The Man Without Qualities also springs to mind.)

The images of storms, eyes, vortices, and hurricanes central to Sandfuture are captivating. Moreover, they give the book its narrative structure. Like a Spirograph toy weaving curves and lines only to leave a shaped, defined void in the middle, or cyclonic winds giving the eye of a hurricane its familiar form, Beal churns his own encounters with Yamasaki’s work with autobiographical ruminations on topics large and small. The result is a book that trades in voids, from Beal’s own experience with loss and Yamasaki’s absence from canonical accounts of modern architectural history to the broken and smoldering remains of his former buildings.

Architectural autobiographies are not new. I suppose that Sandfuture is born under the sign of texts such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s An Autobiography (1932), Sigfried Giedion’s Architecture, You, and Me: The Diary of a Development (1958), Le Corbusier’s Journey to the East (1966), Aldo Rossi’s A Scientific Autobiography (1981), and even Yamasaki’s own A Life. By my reckoning, however, Sandfuture is autofiction in the guise of architectural criticism. Like Rachel Cusk or Karl Ove Knausgård, Beal weaves autobiographical elements into his storytelling. Sandfuture is indebted to Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), 10:04 (2014), and The Topeka School (2019), each notable for a central narrator who is a (very) thinly disguised version of the author. 10:04 seems especially important, not only for the ways in which the formation of hurricanes and their subsequent aftermath shape the narrator’s own purviews but also for the way Lerner confronts death and sickness. Anticipating the title of Beal’s book, Lerner’s narrator writes: “I’ll project myself into several futures simultaneously…. I’ll work my way from irony to sincerity in the sinking city, a would-be Whitman of the vulnerable grid.” In works like these, there is never a question about the author’s literary intent. We can read works of autofiction without mistaking them for biographies or autobiographies.

Sandfuture is different. By inserting himself into the narrative, Beal situates himself against Minoru Yamasaki. And in doing so, he creates a version of the architect that is not historical, but biographical. In other words, Yamasaki is not a historical actor, but an actor in a world constructed by Beal. In this sense, Sandfuture joins a long and broad current of literature that elides the distinction between history, biography, and fiction, works that range from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives to Jorge Luis Borges’s A Universal History of Infamy, Alfonso Reyes’s Real and Imagined Portraits, and Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas. Each of these works uses the biographical format to explore different narrative possibilities.

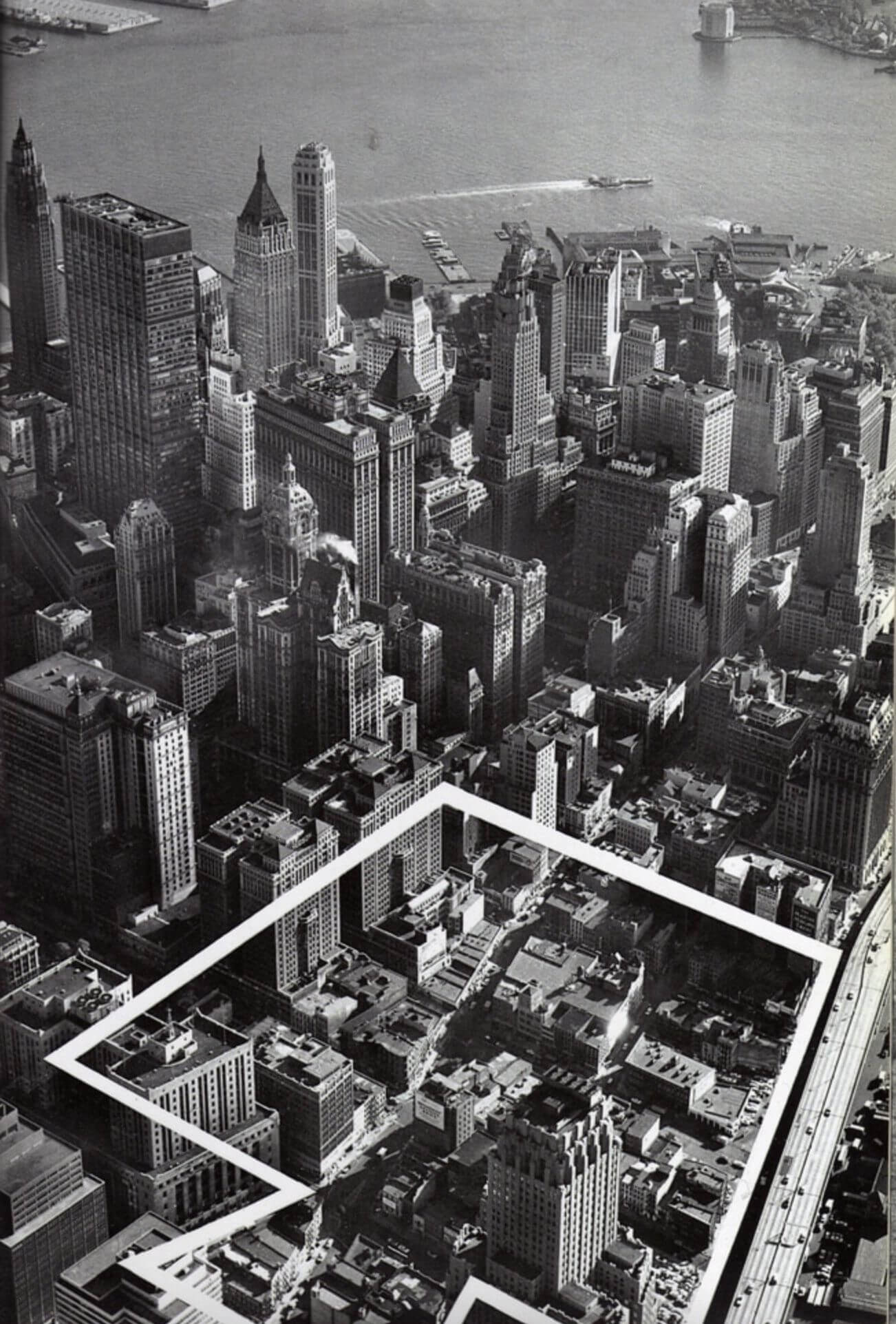

(Found in 1963/64 special Issue of Via Port of New York)

While reading Sandfuture, I thought about Marcel Schwob, the French symbolist writer experiencing a bit of a resurgence thanks to a brand-new translation of his compilation of fictional biographies, Imaginary Lives (1896). In his introduction, Schwob writes: “The book that describes a man in all his irregularities will be a work of art…. The history books remain silent on these things.” Schwob writes as if he were addressing a need that was somehow ignored by literature, longing for writing that focused on lives otherwise forgotten and, by doing so, elevated them to something higher.

Sandfuture may be aiming for something of this magnitude. Beal writes, “Humble as it may have been, A Life in Architecture was Yamasaki’s final attempt to regain control of the narrative of his career and profess his steadfast belief in architecture’s ability to do good.” Beal is also controlling the narrative in such a way as to show that Yamasaki’s beliefs were well-founded. As a writer and reader, I found Beal’s writing absorbing, often electrifying. I cannot think of an architectural monograph that weaves the physiology and etiology of migraines, stories about the art scene in New York, and Minoru Yamasaki’s archives, all while rightly vilifying Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park Avenue—within the span of a few pages, no less. I imagine that architectural scholars and historians may find Sandfuture’s literary ambitions somewhat off-putting. Let them! Writing about architecture can be scholarly and erudite, even as it exists in multiple spheres and is available to as many audiences as possible.

Returning to the issue of historical ontologies and autofiction, Sandfuture is satisfying because it is entirely human and relatable. I learned the importance of this kind of writing early in my academic training, when I realized that the only way to move forward with writing was to do so from my own point of view, to be unabashedly and confidently personal. This is why September 3, 2001, is a day I always go back to. On that morning, I was in the middle of the World Trade Center plaza. Like Beal, I stared up at the twin aluminum shafts that reached into the sky, noticing the cloudy whorls that collected in the air between. Many memories of that morning are lost to time, occluded by the shock of what would happen in a week’s time.

But there are some things I hold on to. I remember that it was a humid morning, the kind that sticks to you like a vaporous shroud. My transit geography was horrible—still is—but I must have taken the 1 or 9 train to Cortlandt Street Station. I went aboveground, bought a coffee, and walked into the Borders bookstore at 5 World Trade Center. I took the escalator to the second floor and hovered in the music section, where I bought a copy of Hot Shots II, the latest album by Scotland’s the Beta Band. In my undercaffeinated haze, I noticed the cover art. The words “The Beta Band” and “Hot Shots II,” drawn as pieces of studded, gilded jewelry, floated in a field of stars. They bent and spun into a vortex-like shape surrounding an explosion. I stared and stared at this hurricane, not knowing that the very place where I stood would become hallowed ground.

Enrique Ramirez is a writer and historian of art and architecture. He teaches at the Yale School of Art.

AN uses affiliate links. If you purchase something through these links, AN may receive a commission.