When Boston City Hall first opened in February 1969, replacing a confined Civil War–era facility just down the street, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable lauded the weighty Brutalist structure for conferring “an instant image of progressive excellence” on an aging, enervated city. She noted how the “rugged,” all-over concrete-and-brick construction was “meant to be impervious to the vicissitudes of changing tastes and administrations.”

In this aim, architects Gerhard Kallmann and Michael McKinnell can be said to have mostly succeeded. City Hall, a building generally unloved by Bostonians, has weathered attempts by multiple mayoral administrations to alter, disfigure, or demolish it. But the 7-acre plaza outside ultimately proved more vulnerable. At present, whole swaths of the plaza’s red bricks have been ripped out as part of a $75 million improvement project initiated by former mayor Marty Walsh. The paving will eventually be restored, but there will also be new additions, including seating, playscapes, platforms for public artwork, and rows of trees.

In 2015, Walsh’s office commissioned a report (led by design firm Utile and landscape firm Reed Hilderbrand) to transform the city’s “front yard” into “the thriving, healthy, innovative space that it should be.” The report resulted in a 30-year master plan for the site, the first phase of which is being executed by multidisciplinary design firm Sasaki and construction management company Shawmut.

For Sasaki principal Kate Tooke, the project presents a singular opportunity to reinvigorate Kallmann and McKinnell’s original design intentions, “to provide necessary upkeep to one of Boston’s most beloved civic spaces and to really focus on making it welcoming and accessible.”

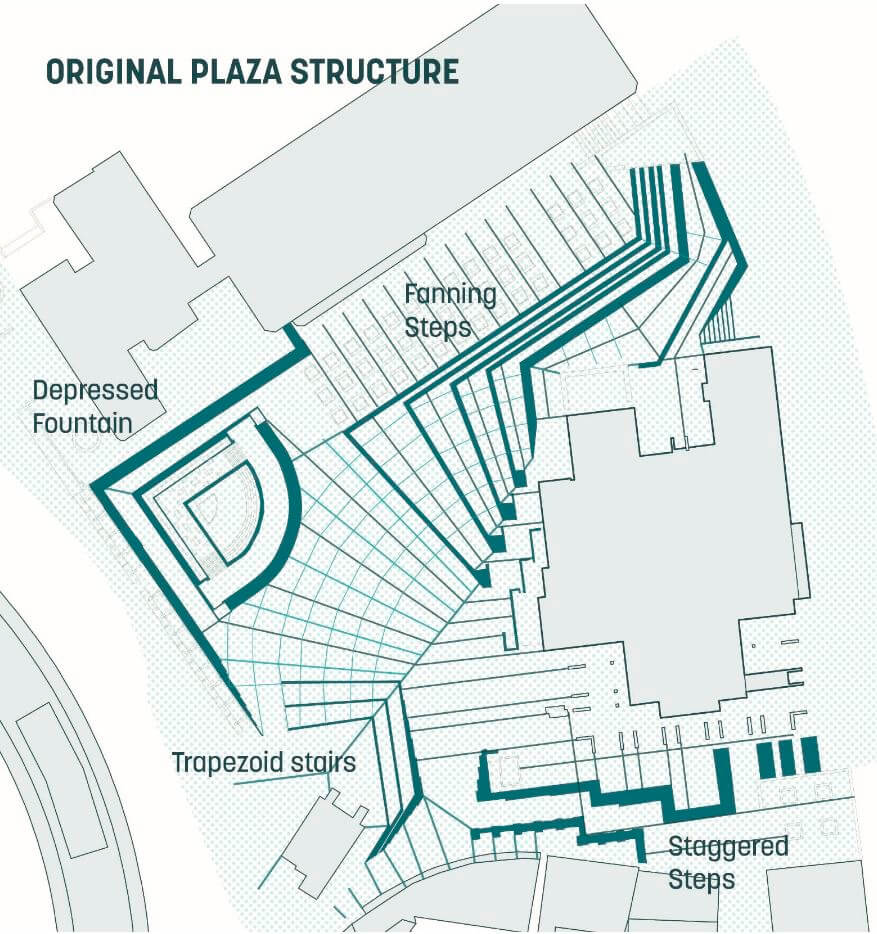

In its initial form, the competition entry submitted by Kallmann and McKinnell featured a sloping plaza that evoked the form and function of Piazza del Campo—the famous fan-shaped central square of Siena, Italy. Tooke describes the realized space, which used terraces to handle 26 feet of grade change, as “a carpet of brick that connects the sidewalks [on Cambridge Street] with the lower, public concourses of City Hall.” But while Siena’s piazza benefits from an active perimeter lined with museums, stores, cafés, and apartments, as well as a de facto amphitheater with regular impromptu street performances, Boston’s version provided few ground-level enticements and offered next-to-no protection from the summer sun or winter winds.

A large fountain across from City Hall, which provided seating space and mitigated seasonal heat, was permanently shut down in 1977 after inspectors discovered that water leaked into the train tunnels below, leaving passersby with little reason to linger in the plaza. The expanse grew increasingly desolate with the relocation of street vendors to nearby marketplaces. Few attempts to rectify the space’s dereliction ever came to fruition, except for Chan, Krieger and Associates’ 2001 designs for a new transit headhouse and wooden arcade along Cambridge Street, both outgrowths of a series of economic studies and design recommendations put forth by the now-defunct nonprofit Trust for City Hall Plaza.

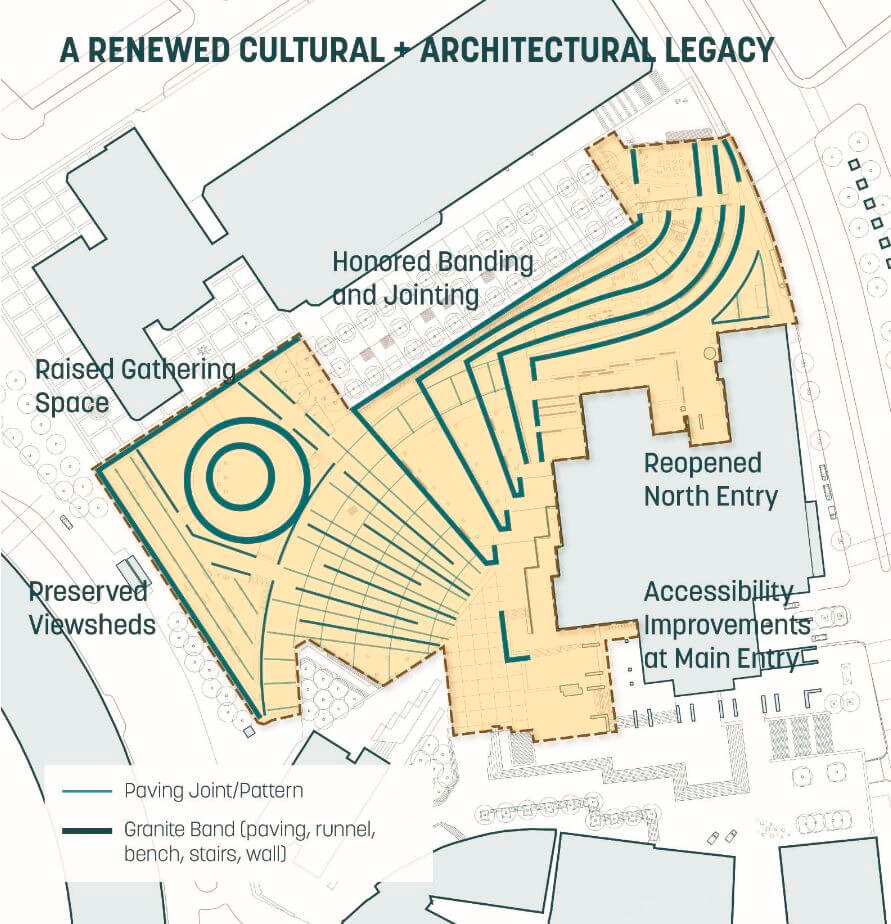

Responding to public input from an extensive community engagement process begun in 2015, Sasaki’s design team integrated amenities and spaces for a wide variety of dedicated and open-ended uses. The firm’s overarching aims to increase comfort and accessibility are addressed through 100 new trees and enlarged plantings, substantially more seating space, clearer wayfinding features, lighting solutions, and universally accessible ramps and entry points. Up to 12,000 square feet of the plaza will be dedicated to children’s playscapes, with 11,000 square feet for public art, and a central open space that can accommodate up to 12,000 people for large-scale events and gatherings.

On Congress Street, which abuts the eastern edge of the Government Center, a new pavilion will provide space for maintenance and mechanical facilities, restrooms, and a potential performance stage. Perhaps even more critically, Sasaki’s design scheme includes a glass vestibule that expands the north entrance of City Hall itself, which has been closed for security reasons since the 9/11 attacks. The newly operable, illuminated access point will reanimate both the streetscape and the building’s interior atria while restoring Kallmann and McKinnell’s original entry sequence.

For iconic civic spaces like Boston City Hall Plaza, maintenance and programming can be as central to the long-term vitality of a project as the design itself. According to Tooke, Sasaki collaborated extensively with the Boston Public Facilities Department and other agencies that will eventually take charge of the site’s upkeep and public programming: “We wanted to design spaces that can be easily cleaned up, reconfigured, and redeployed as something else, in a way that doesn’t cause any damage to the structure. That kind of thinking has been baked into all of the details.” Integrating that level of adaptability into a square that sits on top of some of the nation’s oldest operational train tunnels required several careful structural enhancements, all of which markedly improve the space’s capacity to host intensive events like concerts, political rallies, and protests, as well as ice skating and other recreational activities.

Given the historic and symbolic nature of Boston City Hall, though, the need for design sensitivity extended well beyond the site’s subterranean infrastructure. Sasaki’s team worked with the architect, professor, and conservation planner Mark Pasnik to develop a design that brought Kallmann and McKinnell’s scheme into the 21st century. “With projects like City Hall Plaza,” Pasnik told AN, “I don’t think we should be casting things in amber. It’s about stewarding our existing resources and managing change in a way that engages both original intent and new voices.”

Kallmann and McKinnell themselves regarded City Hall as a robust yet malleable composition, open to the additions and amendments of future generations—much like democracy itself. For Fiske Crowell, a former partner at Kallmann McKinnell & Wood Architects and now a principal at Sasaki, the ongoing work on Boston City Hall Plaza is a natural extension of that narrative, one that will continue to evolve after the first phase’s completion next year. “This project,” Crowell said, “does not complete the entire restoration and renovation of the plaza, but it gets it very far along.”