The fortunes of cities, ever in flux, took a nosedive in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. In New York it seemed everyone with the means absconded to country retreats with their entourage, leaving the less fortunate to get by in cramped quarters that had become terrifying in the context of a killer airborne virus. While now that picture has somewhat reversed, and cities, with their superior vaccination rates, are looking like safe havens from a countryside in decline, it is clear that some of the decentralizing trends of the pandemic, especially in the area of remote work, will have long-term consequences for urbanism.

It was thoughts like these that motivated the directors of the annual Utopian Hours International Festival of City Making, Luca Ballarini and Giacomo Biraghi, to dub this year’s event, which took place in Turin, Italy, from October 8 to 10, the 1,000-Minute City. The theme is a twist on the New Urbanist 15-minute city—an ideal urban environment in which all necessary services can be accessed within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. In the 1,000-minute city, such proximities are not the focus. Instead, Ballarini and Biraghi began by proposing that “the city is now everywhere” and asked an impressively diverse gathering of panelists and presenters—architects, landscape architects, artists, activists, entrepreneurs, municipal officials, journalists, and academics—to discuss their work in light of the Roman concept of civitas, or the social contract uniting citizens under laws that layout both rights and responsibilities. What was up for discussion, in other words, was not so much the making of cities, but the making of citizens.

(Courtesy Superuse Studios)

One precondition for civitas is agreeing on a view of reality upon which to base the law itself, and such a shared outlook has been especially elusive under the divisive politics that are currently roiling the world. Brion Oaks, the chief equity officer of Austin, Texas, spoke about the work his office is doing to establish a common understanding of where and why inequities exist within their city. They harness public data and mapping to reveal a clear dearth of services in historic Black and Brown neighborhoods, but in order to persuade everyone that this is because of structural racism, they rely on metaphor. Oaks uses the parable of the fish the lake and the groundwater, which goes like this: If you see one dead fish in a lake, you think there’s something wrong with the fish. But if you see half the fishes floating belly up, you wonder what’s wrong with the lake. And if all the ponds within a 5-mile radius have half-dead fish populations, you start to suspect that the groundwater itself might be the problem.

This very local example scaled up quite quickly to earth size. Peter Versterbacka, creator of the game Angry Birds, described his plan to link Helsinki, Finland, and Tallinn, Estonia, with a high-speed rail tunnel beneath the Baltic Sea, in quest of talent density and the creation of the “FinEst Bay Area.” This heady vision of tech consolidation and incubation of future billionaires (the proposal included an artificial island bristling with glass towers and yacht harbors) was brought into sobering relief by Kunlé Adeyemi of NLÉ Architects. His presentation focused on the floating architecture his firm has been developing for Makoko, an informal settlement of 80,000 people in Lagos, Nigeria, two-thirds of which is built on stilts over the lagoon. (The first iteration, lashed together by hand from local materials, famously collapsed in a storm after three years; current versions have more robust structures.) Waterfront property, Adeyemi pointed out, is the most expensive, but the water itself is quite affordable. Considering that 80 percent of the world’s major cities, and 50 percent of its population, are by the water and that climate change is elevating sea levels around the planet as well as increasing flooding, learning to live with and on the water seems like a reasonable common purpose.

Some of the most compelling presentations at Utopian Hours, however, did not so much draw attention to inequality, but proposed ways of stitching wounds to create a common ground where civitas could flourish. These were especially in the area of blending urbanity and nature. Robert Hammond, cofounder of Friends of the High Line, appeared remotely to tell the unlikely story of that project’s success, and spoke openly about its downsides, which include overcrowding (the park draws so many tourists that New Yorkers feel it’s not for them) and gentrification (while the public housing projects in West Chelsea remain, the rising commercial rents have pushed out the stores where the people who live there used to shop). Such cautionary evidence has not stopped cities around the world from attempting to make their own High Line, and Turin is no exception.

At the old Fiat factory in Lingotto—whose looping automobile ramp and rooftop test track were famously praised by Le Corbusier as “a guideline for town planning,” and Renzo Piano notably renovated in the 1990s, adding a helipad and high-tech glass globe conference room—local architect Benedetto Camerana has designed a park. Yes, it’s on the roof, floating above the asphalt of the iconic roadway, its plantings all perennials in Piet Oudolf fashion. It is hard to imagine this project, dubbed La Pista 500, attracting the same crush of tourists/international investment as the High Line, and that’s a good thing. It’s an ideal place to have some space around you, take in the stunning view of Turin and the Alps, and contemplate the environmental catastrophe modernity has created, while also seeing perhaps a hint of a path out of this mess in the beautiful plantings and the insects they attract.

(Marcos Ciavone/ Courtesy Benedetto Camerana)

The press flier for La Pista 500 references French landscape architect Giles Clément’s manifesto The Third Landscape, which looks for the future in the leftover places of human conurbation—disused industrial sites, the medians of roads and rails, stormwater ditches, even the crumbling fabric of derelict buildings—places where nature begins to regain a foothold and biodiversity mushrooms. Though Clément did not speak at Utopian Hours, Mette Skjold of Danish landscape architecture firm SLA walked the audience through an array of projects that show a more proactive approach to cultivating ecological systems within city limits. The work is remarkable in the ways that it improves the functioning of infrastructural systems while imbuing the urban environment with pleasantness and wonder. One particularly impactful example of this is Sankt Kjeld’s Square and Bryggervangen in Copenhagen, a cloudburst mitigation project in which SLA removed 30,000 square feet of asphalt from a traffic circle and replaced it with 586 trees of 48 local species, all capable of thriving in the salt-heavy environment of the Danish roadway. The plantings slow the movement of stormwater into drains, preventing flooding and creating a habitat for animals and a sort of healing garden for people.

One might think of nature as the great leveler, and thus an ideal medium for the cultivation of civitas. Yet, the comfortable distance that modern conveniences have put between humankind and the state of nature has created a condition in which experiences and opinions can differ considerably. More direct, immersive contact could be a way of coming to a consonant view—like, say, if we were all to disrobe and jump in the water together. Something like this is behind Flussbad Berlin by German public art practice realities:united. Co-founder Jan Edler showed off the project, which has been in the works for decades and aims to transform the Spree Canal into an amenity for public swimming in the heart of the German capital. The River Spree is a lot cleaner than it was in the bad old days of industry, but when there is a significant rain event the sewers overflow into the river, creating a potentially toxic environment. Flussbad proposed creating a natural wetland environment at the upstream end of the canal to filter and clean the river water while installing bathhouses and swimming platforms at the downstream end. The project is garnering more and more public support, but there is still opposition to it from conservative groups that, according to Edler, recoil at the idea of a public in bathing suits frolicking beneath Museum Island’s Neoclassical edifices. Perhaps they also object to the idea that diverse groups of people might find a common ground while flailing their arms and legs to keep from sinking.

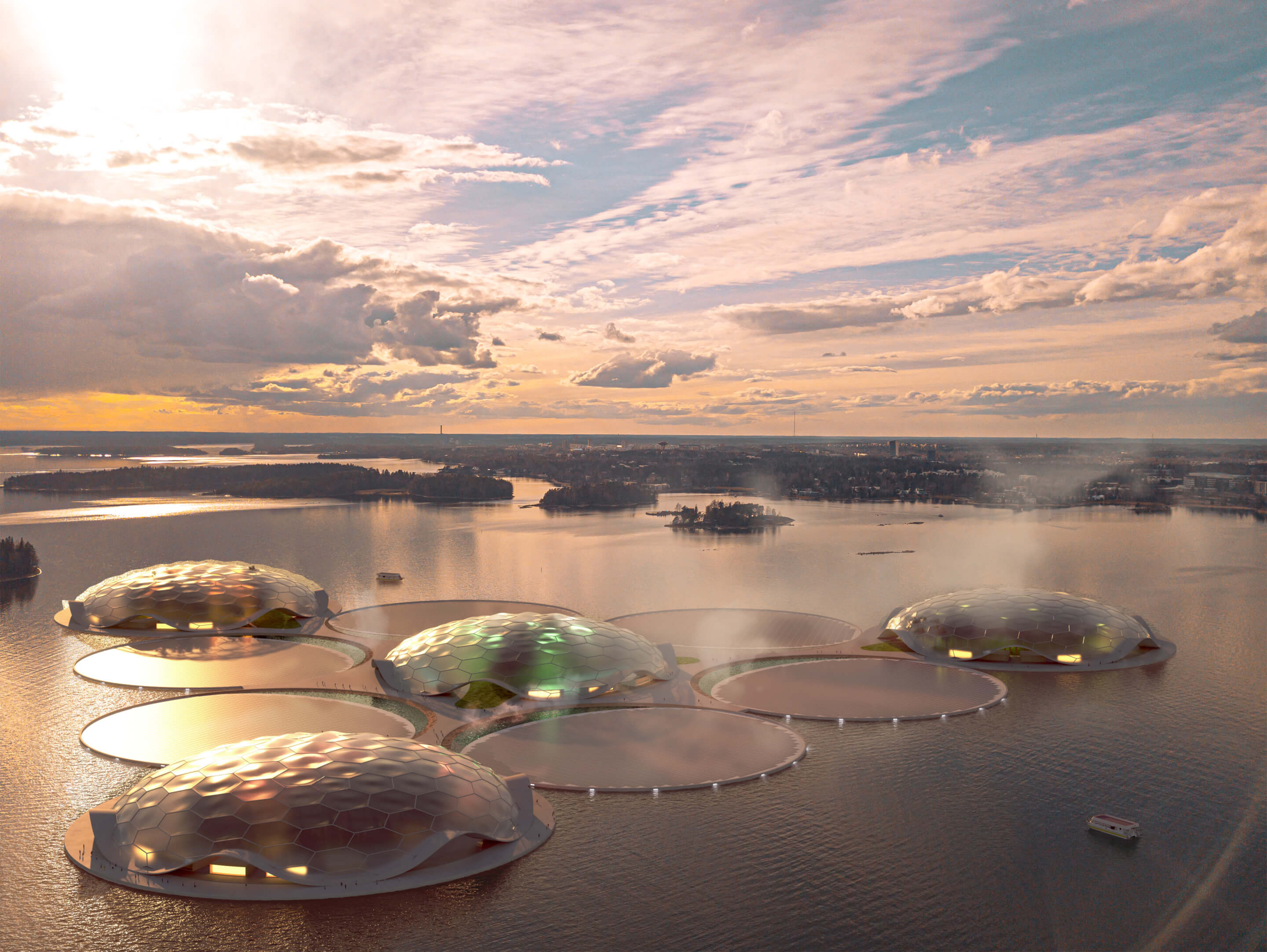

(Courtesy Carlo Ratti Associati)

The impulse to bring nature back to the center of the city was balanced by other efforts to make the human-built environment itself more environmentally sensitive. Césare Peeren of Rotterdam’s Superuse Studios presented his practice’s effort to, as their website states, “create urban ecosystems from valuable residual flows.” The projects Peeren showed mixed passive architectural strategies, recirculating systems, urban farming, and extreme material reuse to make habitations that deny any meaningful boundary between the city and the countryside. Most remarkably, Buitenplaats Brienenoord—a camp run by Foundation Grondvesten on an island in the Nieuwe Maas waterway—reuses 90 percent of a previously existing camp house structure, including the foundation.

The final presentation was delivered by Italian architect/entrepreneur Carlo Ratti, who paraphrased R. Buckminster Fuller’s line from Utopia or Oblivion: If design was applied to global problems, we’d have utopia. It’s a beautiful conceit. But looking at the projects that Ratti exhibited as possible examples of this principle in action—a competition-winning proposal for a thermal battery in the Baltic adorned with saunas and tropical gardens to power Helsinki, and a power-assist bike wheel designed for Copenhagen that failed to take off (Denmark is remarkably flat and not in need of power-assist bikes)—what became more apparent were the limitations of design done in a neo-liberal system that prioritizes private interests over the global good. Mariana Valverde, a professor in the Centre for Criminology and Sociological Studies at the University of Toronto, spoke about one of today’s most trending buzzwords: infrastructure, which she differentiated from public works.

The latter, exemplified by the grand projects of the New Deal, is characterized by large-scale thinking and the harnessing of national resources, while the former is done piecemeal, as money becomes available, often in the form of public-private partnerships, as in the construction of the 19th-century French railroad, from which we inherit the word infrastructure itself. The era of public works, of course, died long ago, withered and enervated by criticism from the right (congressional budget hawks) and the left (Jane Jacobs’s fight against Robert Moses’s heartless urban renewal procedures). But if we are to deal with the global crisis that is climate change, something tells me that a return to grand projets is in order. The notion of the 1,000-Minute City and the cultivation of a world citizenry seems to point in that direction, even as the diverse group of speakers assembled by the directors of Utopian Hours revealed a plethora of sympathetic efforts that seemed to beg for a larger framework of acceptance and support. To really get at Fuller’s prescription for utopia, bigger and systematic thinking will surely be required.