Cairo Modern. Center for Architecture, 536 LaGuardia Place, New York City. Through January 22, 2022.

Two urgent and tragically conflicting arguments emerge from Cairo Modern, a new exhibition at the Center for Architecture. One is that 20th-century modern architecture in Cairo, too often dismissed as inauthentically modern or inauthentically Egyptian, deserves more recognition and respect. The second argument is that it’s becoming ever more difficult to research Cairo’s modernist heritage in the absence of preservation institutions and accessible archives. “In many cases, the published images of the now-demolished buildings used in this exhibition,” the introductory text says, “are the only surviving evidence such buildings ever existed.”

In Cairo Modern, curator Mohamed Elshahed gathers and presents source material for critical debate about Cairo’s modern legacy. (He also makes the argument in his book, Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, released last year.) The exhibition highlights twenty demolished, extant, and proposed works of architecture from the Egyptian capital designed between the 1930s and 1970s. Designed mostly for an emerging middle class, these villas, apartment buildings, civic buildings, leisure spaces, and master plans dispel any illusions of Cairo as a primarily ancient or medieval city. The case studies are supplemented by vignettes on specific building types, architects, urban districts, and historic episodes. Seconded by a team of 15 student volunteers in Cairo, Elshahed conducted his research in the shadow of a repressive state. “I’ve been taken to police stations many times just for taking pictures of buildings,” he told me.

Elshahed, who was born in Alexandria and earned graduate degrees from MIT and NYU, is not trying to prove that Cairo’s modernist architecture was or is all superlative. He insists, however, that it merits serious analysis—contemporary architects need to know the recent, and not just the distant, past—and he protests the erasure of Cairo’s modern fabric because it perpetuates the myth that 20th-century modernism was exclusively northern or essentially European. Cairo became a metropolis in the years after the First World War, when regional and international migration coupled with the rise of the middle class spurred rapid development. Experiments in architecture and urban planning abounded. Somehow these modern and homegrown but not explicitly “Egyptian” projects have been overshadowed by the mud-brick architecture of Hassan Fathy, whose “vernacular” forms aptly criticized international modernism but also provided intellectual cover for denying Egyptian modernity.

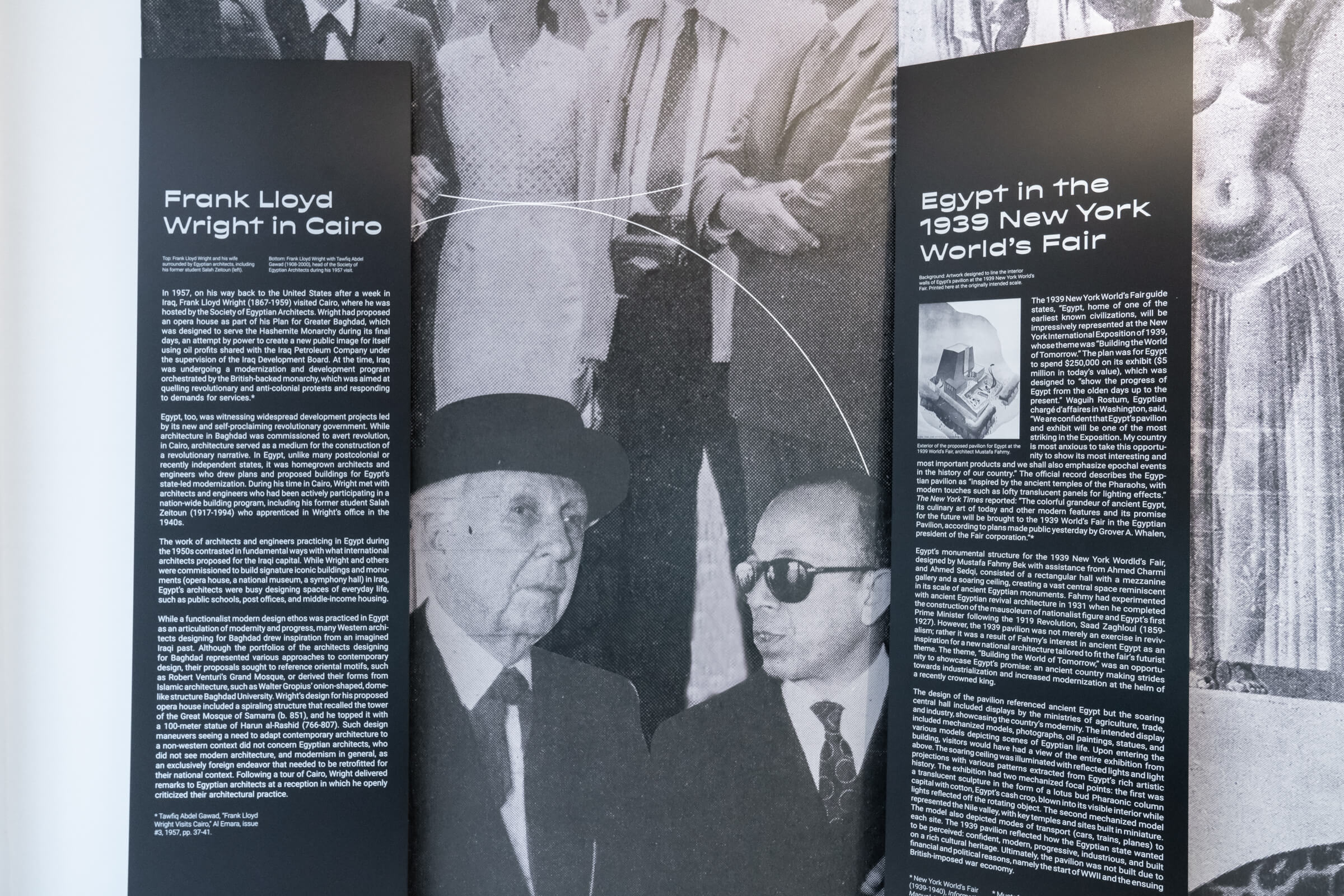

Occupying the ground floor galleries of the Center for Architecture, the show’s Mediterranean pink walls contrast with funereal black casework. Thematic interludes like “5 Points Toward Decolonizing the History of Architecture” and “Frank Lloyd Wright in Cairo” help contextualize the selected works. Wright visited the Egyptian capital in 1957, on his way home from Baghdad, where he was designing an orientalist dreamscape of grandiose monuments, never realized, to evoke a fabled past. Cairo architects were busy hammering out practical spaces like apartments and schools, following what Elshahed calls a “functionalist modern design ethos.” Wright was disappointed. He denounced Cairo’s runaway growth in terms that recall his perennial critique of Manhattan: “cheap and pedestrian… architecture for profit.” Modernity can be mundane. But Cairo’s modern urban fabric also reflected a society striving to free itself from colonial servitude. There was hope in the streets and perhaps in the curves of cantilevered balconies. Social and political promises were draped across concrete structures. Those promises, as much as the buildings that once expressed them, are under attack in the city today.

When I visited the show, another visitor asked me, seemingly at random, “So, who was the Oscar Niemeyer of Egypt?” I looked up from a lightbox panel with image and text describing a relatively banal 1950s housing development. I declined to suggest a Niemeyer analog, not just because the names and projects here were new to me, but also because the question missed the point. Just as Wright had missed the point. Cairo Modern is not primarily a celebration of master form-givers or the art of giving form. Instead, Elshahed aims to survey an overlooked body of work and to reveal its social and political foundations. He’s less interested in stylistic features than in the way architects navigate changing regimes and economic systems, and how local and global currents intersect. That’s why he covered a wall with a timeline that mixes architecture-related events in Egypt with architecture abroad and cultural and political milestones in Egypt and abroad. In 1932, the year of MoMA’s exhibition on the so-called International Style, the Egyptian-born, French-educated architect Charles Ayrout completed a sleek modernist villa in Cairo; in 1952, the year Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation was completed in Marseille, a coup d’état in Cairo launched an era of state-sponsored construction.

Though Cairo Modern highlights the contributions of numerous architects to the midcentury milieu, one figure soars above the others: Sayed Karim, a prolific architect, planner, and writer who was professionally active from the 1930s to 1965, his career cut short when politicians, wary of his influence, placed him on house arrest. Painfully aware that his European contemporaries (including his colleagues at ETH Zurich, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1938) doubted whether architects from the Arab world understood the significance of concrete and steel, he founded the architectural journal Al-Emara in 1939 to promote and publicize modernist projects in Egypt and beyond. Karim rejected essentializing views of architectural form and espoused a kind of technological determinism, at least in a 1940 quotation emblazoned across a gallery wall: “The shapes of arches, the dimensions of columns and the thickness of walls are determined by the physics of materiality and the methods of construction.” It’s not clear whether Karim designed any excellent buildings, but the examples gathered here, suggesting discipline tempered by imagination, convinced me that his work mattered.

National identities appear fluid in Cairo Modern, where the high-rise architect Naoum Shebib, who was born in Cairo and died in Canada, is described as “an Egyptian architect of Jewish Syrio-Lebanese origins.” Architect Mario Rossi, born in Rome, moved to Egypt in 1921 and died there in 1961 after an illustrious career. I asked Elshahed whether the artists who designed the murals for Egypt’s unbuilt 1939 World’s Fair pavilion were Egyptian. “It’s hard for me to answer that question,” he said, adding that he takes a critical view of national categories in a cosmopolitan context. I got it. Nationality is a social construction that can obscure more than it reveals. The architecture in Cairo Modern is not essentially Egyptian. It’s an essential part of the story of modern architecture, centered in a hub of colonial and postcolonial development.

And the modernity that Cairo Modern seeks to recover is more than the record of lost buildings. It’s also the lost modernity of an open metropolis where architecture belongs to everyone.

Gideon Fink Shapiro is a Brooklyn-based critic, historian, and curator.