BITS, an exhibition on view at a83 in SoHo, offers a confetti of prints and projects to welcome us back into the shared material world of architectural discourse. The show highlights the magic that can happen when the materiality of representation is taken as an impetus for experimentation. It’s in the little things. Light glinting off gold ink. Collages composed with care. The visceral hue of a blueprint. Prints on paper, on acetate, on porcelain enamel-coated steel. Drawings worth framing.

The exhibition is comprised of 44 works by ten architects and artists. Some are well known, like a multi-layered drawing of the molded plastic and sheet metal Dymaxion Bathroom by R. Buckminster Fuller. The prints of Villa dall’Ava, Parc de la Villette, and Boompjes Tower Slab by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA are standouts. The villa prints, incidentally, depict an early version of the project with a rooftop canopy and tilted, rainbow-colored piloti, which serves to highlight the overarching ethos of the show: The discipline of architecture is better when drawings are allowed to take on a life of their own.

The timing of the show is perfect, following months spent online that have probably reinforced deleterious habits of digital production, including the tendency to equate “output” with a click of the Print button. As the pandemic recedes and climate change fills the vacancies left in the news cycle, we are reminded that ignoring the material world around us can be perilous. I suspect that the return of the real that’s underway will play out in a variety of forms, and I hope that architectural representation will be one of the areas to be brought to light and reimagined. Computer software has reinvigorated architectural image-making, but the labor, the techniques, and the craft of representation remain as subterranean as ever. As a result, drawings are imagined to be immaterial and ephemeral—no sooner created than disposed of. What would a more sustainable ecology of practice look like?

BITS shows how it pays to consider the craft of media. Many of the works on display come from the archive of John Nichols Printmakers, whose SoHo space played an important role in connecting architects, artists, and gallerists throughout the 1980s; at a83, the drawings of buildings certainly count as works of art. This elevation of architectural drawings seems to happen naturally when architects focus their attention on materials and methods of representation. The Mistake Prints series by Takefumi Aida, for instance, comprises what appear to be torn and misprinted blueprints, with the gaps and misalignments becoming moments for design. The spirit of cross-media experimentation is also evident in an unusual work by RUR/Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto; called The Shadow Theater, it is a steel screen of the type used for printmaking, with lines and text in emulsion. It looks like something along the lines of Daniel Libeskind’s Micromegas and remediating the printmaking technology as the artwork itself doubles down on the spirit of deconstruction.

Seen as a whole, however, BITS is less about self-involved worlds than the more expansive constellations of objects with which we share space. Several of the most compelling pieces are by figures who are not common points of reference in architectural circles, though they fit contemporary sensibilities nicely. There are paintings of birds, insects, a dog, an exit sign, and squash (by Samuel Oak Tippett), a collage of paper, string, and plastic toys (Stephanie Brody-Lederman), and prints of tools, chairs, and suit jackets (Charles Luce). The show shares a penchant for lists with prominent figures in the recent turn to objects—the likes of Graham Harman in philosophy, Kathleen Stewart in anthropology, and Mark Foster Gage in architecture. There is also a similar emphasis on interesting or unusual “qualities,” a code-word for heightened aesthetic experience favored by proponents of object-oriented ontology. This seems like a fruitful direction for architects to take, and it has historical precedents. The work in BITS spans more than four decades, with much of it arriving from the era of “paper architecture,” a period of economic doldrums that left architects with plenty of time to speculate elaborately through images without the burden of building. Sound familiar?

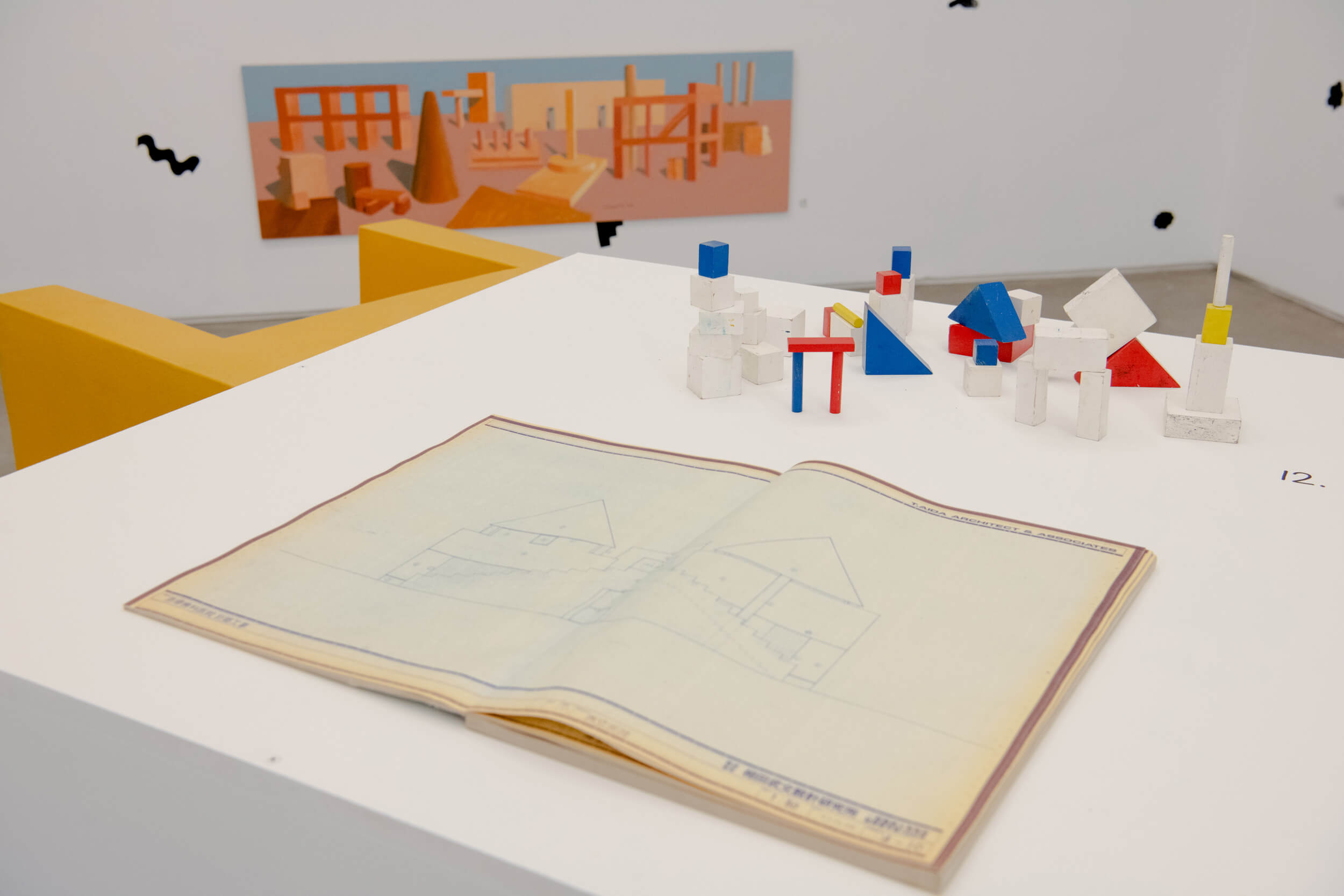

For all its echoes of a bygone era, the recent return of drawing, as Sam Jacob has called it, has been oddly immaterial. The focus has been on the content of drawings, not the physical manifestation of drawings themselves. This has left architecture doubly removed: the discipline is no longer about built buildings, but representations of buildings; not about actual objects or media of representation, but the ideas represented therein. BITS turns in another direction, allowing space to emerge in the resonance between things. A beautiful book of drawings by Aida of his Toy Block House project sits alongside painted wooden blocks waiting to be played with; these lead you across the room to paintings of quasi-Platonic architectural fragments by Charles Moore, to various colors and shapes scattered here and there, and finally up to the ceiling with a bit of plumbing painted bright red. Space is not created within drawings, but among things.

BITS prompts us to rethink the recent return of drawing as a turn to printing that was never finished. It seems like just the dose of physical reality architecture needs. I, for one, am ready to take discussions of architecture into the public realm after months spent more virtually and more domestically than I’d been accustomed. a83 is an ideal type of semi-public space—a space where architectural shop talk can combine with discussion of the world we want to inhabit together. And BITS shows how architects can help furnish the real world of the discipline of architecture with compelling things.