Like in years past, historic preservation played a starring role in many of AN’s top-trafficked stories of 2021, particularly stories that drew ire both online and in real life.

While those controversy magnets have been compiled by AN’s editors in a separate end-of-year roundup, below is a look at five additional preservation stories that proved popular in 2021. As for those not listed below, there are countless other preservation-related stories published over the past 12 months worth revisiting. It was a year in which Brutalism took a number of (sadly predictable) hits, an early Frank Lloyd Wright home dodged demolition, multiple historic structures were transformed into Apple Stores, and a Mies masterpiece in Berlin emerged from a top-to-bottom refurbishment that began in 2016. It was also a year that began with a violent insurgence within the United States Capitol complex that resulted in millions of dollars in estimated damages to the historic “People’s House.”

Illinois will sell the Thompson Center for $70 million

Perhaps the single largest preservation story of 2021 was one of triumph (but with a warranted side of caution): the saving of the Thompson Center, a postmodernist governmental office building in downtown Chicago that was feared as lost when the State of Illinois officially announced plans to offload the Helmut Jahn-designed landmark in May. The announcement of the long-time-coming sale was accompanied by a supertall tower-permitting zoning change for the highly coveted North Loop development site that effectively served as a death rattle. That death rattle, however, only increased the sense of urgency among preservationists from Chicago and beyond rallying for the adaptive reuse of the spaceship-esque 1985 building famed for its soaring, 17-story atrium. Seven months after the site first went up for sale (and after the tragic death of Jahn), Governor J. B. Pritzker announced its $70 million sale earlier this month to a developer keen on modernizing the building, not razing it. While the Thompson Center will indeed stay standing thanks in large part to preservationist groups who never removed their collective feet from the pressure-pedal, there is skepticism over the initial redevelopment plans, which appear to erase and/or tone down the most exuberant design elements of Chicago’s singular “Postmodern People’s Palace.”

The Farnsworth House is renamed to honor Edith Farnsworth

The National Trust for Historic Preservation’s October rededication of the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe-designed Farnsworth House involved the addition of only one single word to the iconic (and flood-prone) site’s name. However, that word, the name Edith, carries significant importance for the Trust-owned and -operated house museum situated along the Fox River in Plano, Illinois. “We hope this seemingly simple act of inserting her first name has the larger effect of inserting her into the ongoing history of modern architecture,” explained Scott Mehaffey, executive director of the Edith Farnsworth House. “Without Edith Farnsworth, Mies van der Rohe’s American career might have remained stalled and his stature usurped by his contemporaries. Edith was fully aware that she was both a client and a patron, and she played an active role in the design of her house, which has become a celebrated milestone in the evolution of modernism.”

Richmond’s Robert E. Lee statue has been taken down

Myriad Confederate monuments across the country were brought down this past year including perhaps the most notorious of them all: a 12-ton bronze equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee anchoring Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, that was detached from its soaring marble plinth via crane on September 8. The removal of the 60-foot-tall statue marked a new beginning for Monument Avenue, a storied strip within Richmond’s National Register of Historic Places-listed Monument Avenue Historic District that, not that long ago, was populated by a total of five Confederate statues. The Commonwealth-owned Lee monument was the last to go following a unanimous ruling by the Virginia Supreme Court that ended ongoing litigation and permitted Virginia Governor Ralph Northam to proceed with his removal plans. “After 133 years, the statue of Robert E. Lee has finally come down — the last Confederate statue on Monument Avenue, and the largest in the South,” said Northam in a statement. “The public monuments reflect the story we choose to tell about who we are as a people. It is time to display history as history, and use the public memorials to honor the full and inclusive truth of who we are today and in the future.”

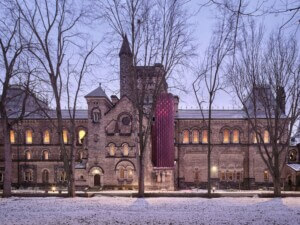

A Harry Weese-designed bank in Columbus, Indiana, begins second life as a coffee shop

While a considerable amount of conflict, controversy, and legal maneuvering accompanied many of AN’s top preservation-focused articles of 2021, one photo-driven story documenting the adaptive reuse of a 1961 bank building in Columbus, Indiana, was notably squabble-free and prompted positive reactions from readers. Earlier this year, Tyler and Alissa Hodge of the Columbus-based Lucabee Coffee Co. opened their second location within the landmark former Irwin Union and Trust Bank at the city’s Eastbrook Plaza just in time for the 2021 exhibition of Exhibit Columbus. Consulting with the Landmark Columbus Foundation and historic preservation experts, the Hodges carried out a reverent and light-touch conversion of the Harry Weese-designed bank locally referred to as “the dead horse” building. Per the Foundation, the interior revamp was “inspired by the modern design of that era, featuring black, wood, and grey elements and a nod to the original interior with an open view to the vault.” And, yes, the original drive-thru banking windows were restored and are serving a new generation of customers.

Liverpool loses its UNESCO World Heritage Site status

Although former Liverpool Mayor Joe Anderson officially put the kibosh on city council-approved plans for a high-flying zip line attraction that would have sent shrieking tourists sailing through the historic heart of the English port city in the summer of 2020, the damage, so to speak, in the view of UNESCO had already been done. Just weeks after publishing a formal report warning that Liverpool’s 300-plus-acre historic core was at grave risk of being stripped of its World Heritage Site status due to “serious deterioration and irreversible loss of attributes,” members of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization voted in late July to officially delist Liverpool. Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City is only the third World Heritage Site to be delisted by UNESCO since the prestigious program was first established in 1978. While UNESCO’s decision was shocking—and deeply embarrassing—to many Liverpudlians, Jason Sayer explained for AN that this heritage calamity on the banks of the River Mersey has been slowly unfolding for well over a decade due to unchecked waterfront development.