There are periods when, rather than forcing the gates of the future open, our technical and cultural productions tend to mirror the present. This year, 2021, seems willing to join this category, and so does its big worldwide gamble, Expo 2020 Dubai (the pandemic delayed the opening by a year, but brands are meant to endure), which has recorded over 5 million visitors since opening on October 1.

As I was covering the Expo preview for Italian architecture and design magazine Domus, I enjoyed my personal share of global history: seeing the carbon fiber Expo Gates welcome the first visitors, seeing the machine start to get its cogs going—almost unpredictably, because of the fierce climate that boiled everyone’s nerves by teatime—and seeing its attractions and contradictions, both material and immaterial, start to emerge.

In an Expo that is meant to be more business-oriented than public-engaging, much of 2021 is represented, although most of its built shapes date back to pre-pandemic 2019. This is perhaps further confirmation that the post-pandemic (if the coronavirus’s endless variations ever allow us to get there) has only sharpened processes that were already underway. Italian journalist Vincenzo Nigro, for instance, hot off the Expo’s opening, highlighted in Repubblica some rather eloquent visual clues in political terms, such as the emptiness of the Afghan pavilion, India and the United States’ muscular expressions of global power, and the tensions between some participants written clearly in their well-marked distancing.

The more we get into the architectural realm, the clearer such indices of the newborn 2020s appear. First, bigness: as non-stop growth and land consumption make alarms ring all around the globe, the Expo 2020 site is 4 times larger than Expo 2015 (which took place in Milan). The three subthemes—Opportunity, Mobility, Sustainability—create a tripartite site symmetry that fortunately mitigates both the heaviness of the monumental axis connecting the metro to the central Al Wasl dome, and the feeling of accessing a desert motor city wrapped by parking lots. Still, once inside, it is all about long-distance walks, punctuated by unsuccessful attempts to seep in through the pavilions’ open areas. Despite the “landscaped selfishness” of these buildings, their visual juxtaposition creates once again that theme-park polyphony that we are accustomed to seeing at Expo.

Second, style: in such mirror-like phases in the history of World’s Fairs, some “Expo Style” architecture is easier to detect, as an amplified echo of all those contemporary design themes that have crystallized. We can come across “awe-bjects,” such as the interactive light-beam-shaped sculpture of Es Devlin’s UK Pavilion; monumental expressions like Calatrava’s gigantic steel falcon for the UAE; the persistence of some international high-tech represented, for example, by the entirely recyclable structure of LAVA’s German Pavilion, or the large canopy of the Opportunity Pavilion, designed by the Spanish-Kuwaiti firm AGi Architects. And although the focus on natural materials is strong, with wood from the Swedish forest and rammed earth in the Moroccan pavilion (by O+C), it’s all once again about facades, be they media interfaces like the UK’s interactive digital poem and Kuwait’s video wall, or true mirrors, like the powerful welcome piece of the Switzerland pavilion by OOS.

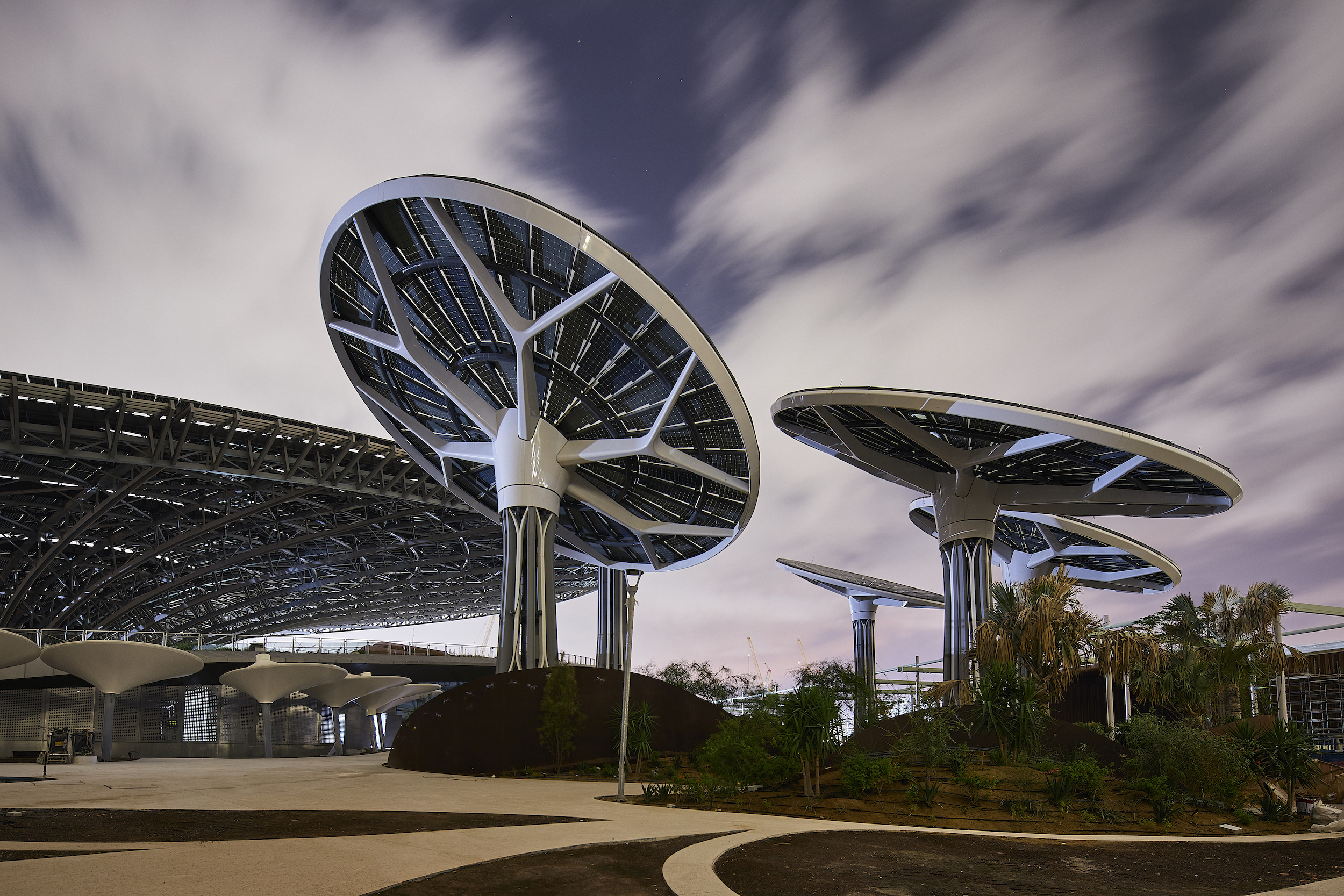

When it comes to sustainability, contradictory tensions peak. The entire sector that the Expo dedicates to this theme (one-third of its surface area and the majority of the narratives structuring its design and operation) borders on augmented reality. The very pinnacles of this experience are where the visual dissonance is at its greatest. There is an almost complete circle of waterfalls raining their precious liquid down onto the desert floor from 43 feet in the air. The Sustainability Pavilion itself—a 426-foot diameter steel flying saucer by Grimshaw & partners surrounded by steel solar mushrooms, encrusted with 4,912 solar panels, emblazoned with the highest LEED ranking achievable, trumpeting concepts such as the ecological footprint—is undercut by the fact that its built footprint is anything but minimal.

The organization of the Expo also gave an easy out for countries who wished to leave the question of sustainability unanswered. Frontline opponents of the coal reduction agreements at the recent COP26, for instance, could elude the environmental debate by finding their spot in the Opportunity district, or other less challenging areas. It must be said that not all environmental issues at Expo 2020 are magnified by narratives only to be immediately disavowed by facts, several participants address them in more-or-less radical ways. In some pavilions, for example, the Dubai heat seemed to take over the exhibition space. This was the case for Germany, where only a few boxes are air-conditioned within a much larger envelope, and Italy, which enveloped its pavilion in a recycled-plastic-rope curtain. Spain harnessed the stack effect with towering conical voids that alleged to create a comfortable environment but buried the majority of its exhibition spaces under the ground.

Others worked on recreating specific biotopes (as Austria did in 2015, bringing the air of its forests to the outskirts of Milan). At the Dutch pavilion water extracted from the desert air is turned to rain, and conceptual and real forests appear at Sweden’s and Singapore’s pavilions respectively.

Some of Expo 2020 Dubai’s exhibits are undoubtedly unique interactive design projects, but most of the content shared with the public could easily be conveyed or experienced online, or in VR, as happened with the expo construction site visits during the pandemic lockdown. Why visit, then? Because, once again, Expo has done its magic. Whether its designers have been smart or not so smart, it provides the densest global picture of the contemporary, which would be very hard to grasp anywhere else. More specifically, it is the physicality of its spaces that makes this Expo worth visiting—especially those minor ones hosting our endless sweaty walks, our dignified queueing, perhaps the residual temptation of some Lost in Translation fantasy. This physicality, actually being there, allows us to grasp that sometimes diffident, sometimes enthusiastic intersection of different proxemics; the different ways in which labor, salability, consumption, and power occupy space; the way the things of the world are, mostly unconsciously, staged and practiced in a scale model of the world itself.

2021 has been the year of the metaverse. We have seen that our lives, including all hopes, claims, even injustices we feel the urge to fight, are as real in the different metaverses we join as they are in physical space. Still, the way such dynamics are performed and practiced in the physical realm of what we could still call the Expo’s public space (despite the ticket one must purchase) should not be forgotten. Claiming for at least a Henri-Lefebvre-ish interpretation of space as a social product, of public space as the product of contrast, of conflict sometimes, this Expo can still be a worthy and unique chance for a synthetic and clear perception of the contemporary, including its sweat, but hopefully not its sandstorms.