The City of New York has neared completion of its demolition of the southern portion of East River Park, a green space that has served the Lower East Side for over eighty years. Originally constructed during Robert Moses’ tenure as the city’s controversial master builder, the park sits on waterfront land that government officials deemed critical for ongoing resilience projects in Lower Manhattan.

When Hurricane Sandy devastated the New Jersey coast and much of New York City in October 2012, the Lower East Side was one neighborhood that faced significant flooding. Storm surges returned water to Manhattan’s coastline to its original form, effectively negating decades of land reclamation and expansion. In the years after the storm, federal and local government agencies launched ‘Rebuild by Design,’ a competition that tasked architects, planners, and engineers with developing systems that could protect New York’s low-lying coastal areas.

One of the winning designs, BIG and ONE Architecture’s “Big U” plan, proposed a comprehensive system of walls, berms, and landscaped knolls tracing the edge of Manhattan from the east side to the west. The Department of Design and Construction (DDC) whittled down the idea to a smaller impact area and rebranded the particular portion affecting the Lower East Side and the scheme is now known as the East Side Coastal Resiliency project.

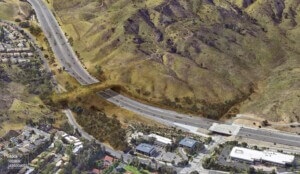

Years of community outreach and town hall meetings molded the idea into a plan that rested primarily on a sloped berm on the western edge of East River Park, abutting FDR Drive. Requiring an investment of around $760 million, the reinforced hill would be coated in grass, protecting the neighborhoods on the other side of the elevated highway from floodwaters. East River Park itself would be allowed to temporarily flood during major storm events–a strategy that reflects natural wetland landscapes and engineering techniques adopted in the low-lying Netherlands.

With city agencies preoccupied with fears that the plan’s construction would interfere with the flow of traffic on FDR Drive and subterranean electrical wires operated by Con Edison, though, the grassy berm was abandoned. In its place, former mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration opted to purse a scheme that would cost twice as much. Over the course of several years, the city planned to demolish the entire existing park, adding 8 to 10 vertical feet of landfill along a 1.2 mile-long flood wall.

Rather than allowing floodwaters to inundate parts of the park periodically, the city would essentially erect a levee to keep waters out permanently, or at least until 2050. A new park, similar to the decades-old East River Park, is slated for construction on top of the infill.

Last April, as the city prepared to execute the plan, disgruntled residents and park users organized large protests and took legal action against the municipal government. By November, the Appellate Division, First Department granted a restraining order that offered a glimmer of hope that the work would be paused, but the city went ahead and began to cut down 380 of the park’s 991 mature trees. Officials argued that the order did not require a pause, continuing work under the protection of a small army of police officers. On December 16, another court overturned the restraining order, leaving activists with few other options to oppose the project.

Specific concerns vary from resident to resident, but complaints tend to center on a construction process that will leave the neighborhood without a major green space for years until the new park is built. Many residents have also spoken out against the destruction of habitats for local wildlife and the air pollution that will likely accompany the heavy machinery needed to build the levee. And while 1,800 trees are planned for the new park, none of them will be as large and mature as the 80-year-old trees that have now been reduced to stumps.

More than anything, though, general discontent seems to frame the East Side Coastal Resiliency project as a top-down endeavor that reflects little care for the expressed opinions and needs of the people who use the park most. Only the coming years will reveal whether the park’s shiny replacement brings solace to those community members who challenged its destruction.