In early February, workers at SHoP Architects in New York City dropped their petition to unionize the firm’s 135 employees. The decision, which ended a high-profile organizing drive, was gutting to many. Had the SHoP staffers succeeded, they would have established the first private-sector architects’ union in the United States since 1947. Still, their attempt gave real-world shape and stakes to what some in the architecture world, myself included, have been talking about for years: Architects are quickly proletarianizing. That is to say, they are starting to see that hitching their wagons to the idea of professional exceptionalism, to the hope that they might one day be firm owners, to the dream that someone with enough money will like their work enough to build it, is a dead end. They are instead betting on solidarity with the working class, first and foremost by recognizing their own status as workers.

Marisa Cortright’s short new book makes this same case, only within the European context. The pamphlet follows the thrust of her 2019 article “Death to the Calling: A Job in Architecture Is Still a Job,” published in the web publication Failed Architecture. Cortright’s irritation at the field’s self-perception shows in her studied avoidance of the term “architect”; she opts, instead, for “architectural worker.” While I found other terminological choices less clarifying—particularly her use of the sociologically spurious “professional-managerial class”—her messaging is admirably consistent across the book’s three essays (“Architecture,” “Europe,” and “Organizing”).

Drawing on interviews with designers living in and outside the European Union, Cortright paints a picture of what it’s like to work as an architect today and what possibilities for organizing already exist. Some snapshots appear rosier than others: One Spanish architect, for example, works with her husband “primarily on single-family homes” and seems to be comfortably self-employed. Others are bleaker, such as when an architectural curator describes her boss’s dismissive attitude toward equal pay. They are all inflected with the lonely sentiment expressed by the quote, taken from the Yugoslav writer Ivo Andrić’s novel The Bridge on the Drina, from which the book’s title is derived: “No one recognizes your efforts and there is no one to help or advise you how to keep what you have earned and saved. Can this be? Surely this cannot be?”

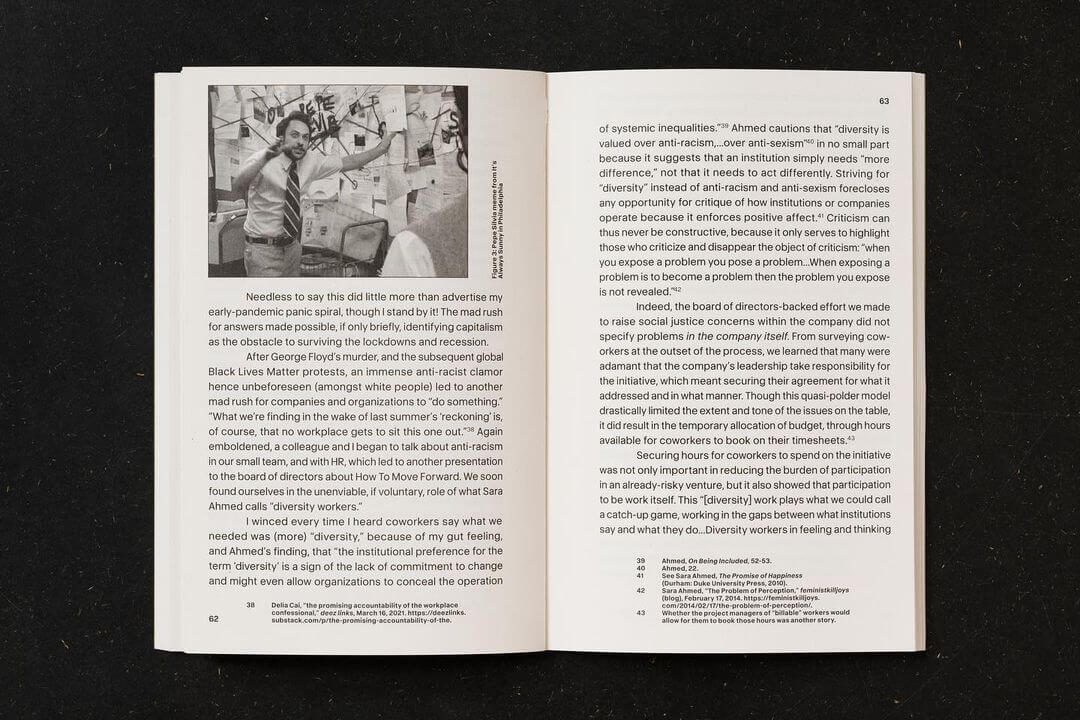

From these vignettes, it becomes clear how organizing could lead to an identity crisis for architectural workers. The “calling” being what it is—per Cortright, an imperative “not to complete some task or travel somewhere,” but to “become something”—many might find it difficult to accept the full implications of a union, i.e., that it is inherently antagonistic to their bosses, even well-liked ones. Cortright notes that architectural workers are inculcated with certain beliefs from the very beginning of their education—for example, that designers work either solo or as part of a nonhierarchical team—and that those beliefs have created within the architecture profession cultural obstacles that stand in the way of collective solidarity.

But these obstacles aren’t merely cultural. By all indications, SHoP bosses perceived the union drive as a threat to the firm’s bottom line. (After declining to recognize the union, SHoP retained the services of a top New York law firm specializing in union-busting.) At the same time, its staffers weren’t moved in sufficient numbers by a message that closely resembles Cort-right’s. Perhaps they still hold to the upward-mobility wager, which leads ineluctably to self-employment. In that case, it’s not surprising that they would chafe at the idea of identifying as members of a class with a different set of interests.

Change is possible, however, and those in the design professions are increasingly becoming conscious of their class positions. A Swedish interviewee tells Cortright that the country’s architects’ union “is also an employers’ association, [which] means I’m not organized. I stayed far away from that association.” From this, Cortright draws the pragmatic conclusion that “there is no ‘us versus them’ when both are under the same roof.” An interview with a member of the Section of Architectural Workers of the London-based independent union United Voices of the World (UVW-SAW) deserves to be quoted at length:

I feel like I’m at a really interesting point in terms of how I see political action, because I’ve gone from very much, ‘oh, we don’t need the union’ in the space of [three to four months] to, ‘we really do need the union.’ I’m still trying to get my head around the fact that stuff won’t change unless someone’s pushing for it. Ultimately I think none of us really want to get into a fight, but all of us want stuff to change. And I still need to go through that process of realizing stuff isn’t going to change without putting up a fight.

UVW-SAW, along with the Future Architects Front and Foreign Architects Switzerland, which also feature in the book, represent a rising left wing in the architectural field seeking to improve material conditions of workers within it. Addressing these and other organizations, Cortright’s short volume is a good exploration of what the possibilities in organizing are, even as it also stresses that organizing efforts will necessarily vary by context and might even extend into the online realm. At the book’s conclusion, she cites an Instagram poll conducted by the architecture meme account @dank.lloyd.wright, whose purpose, evidently, was to demonstrate architectural workers’ desire to unionize. (Asked whether they would join a “dank lloyd wright union,” 94 percent of respondents answered “yes.”) But while there is certainly a labor-friendly attitude among architectural workers, especially those who spend time on social media, the existence of the poll itself shows that there is still perhaps a fuzzy understanding of where unions get their power. Unless all of the respondents worked in the same workplace (remember, this is a meme account), unionizing would give them little leverage, if it was possible at all.+

Still, Cortright’s willingness to take @dank.lloyd.wright and put its work in conversation with IRL organizing efforts gestures toward a level of growth—and growing political differentiation—within this broadly construed left wing of architecture.

But perhaps the most useful part of the book is the breakdown of how Europe was politically and legally constructed, spelled out in the middle essay, wherein Cortright distinguishes between the working conditions of EU nationals and non-EU nationals. While the former experience a certain level of mobility—still always tethered to the whims of the market—the latter don’t enjoy such freedom and are hamstrung by tough competition with their EU counterparts for jobs that end up driving down wages for both groups. Architectural workers in the U.S. would benefit from a similar analysis, specifically as it pertains to divisions within their profession, so that they can better understand the conditions under which they organize. Overall, “Can this be?” poses more questions than it answers, which might be indicative of Cortright’s attitude toward the topic but also of this nebulous political moment, in which everything seems like a possibility, in which the old order is clearly not working, but a new order is not yet in sight—nor is it clear exactly how it’ll come about.

Marianela D’Aprile is a writer living in Brooklyn.