Difficult as it is to choose, I do have a favorite episode of Frasier. Season 10, episode 11, titled “Door Jam,” revolves around La Porte d’Argent, a new Seattle day spa frequented by high-profile socialites that Frasier and Niles are dying to get into. They eventually scheme their way into the club and have the most pleasing experience of their lives—until they find out about an even more elite level of membership locked behind a golden door. So off they go again plotting to unlock further access, spending gobs of money along the way. During a post-treatment scene in a room dubbed the “relaxation grotto,” the Crane boys eye a platinum door at the very back of the spa. By now out of patience, they simply barge in—only to emerge in a grimy alleyway, locked out of the establishment, naked and covered in various powders, wraps, and sliced fruit. In her infinite wisdom, Frasier’s producer Roz Doyle sums up the episode’s arc: “The only reason why you want to go there is because you can’t.”

For me, “Door Jam” is a fitting allegory for the emergence of metaverses and NFTs, which seem prone to the same sorts of status and exclusivity-based upselling, as well as the fraud and emptiness that lie beneath the surface or, rather, just outside the door. And yet, even within architecture, views on the subject are mixed. Everyone I speak to is either hell-bent on telling me that virtual worlds are the future of space-making as we know it or the most dishonest manifestation of manufactured scarcity to date. A sweeping judgment of metaverse space seems impossible.

A metaverse is any interactive online space that allows for open participation and shared stewardship. An NFT (non-fungible token) is a blockchain-secured digital asset existing in the metaverse; it can take the form of an artwork, currency, or just a cool hat that your online avatar can wear wherever “you” go. While it remains unclear what its exact parameters are, the metaverse isn’t a “new” invention per se. Backed by a relentless marketing campaign, it rebrands older, existing platforms such as Second Life, a free and open source metaverse that has been around since 2003. It would even be wrong to speak of the metaverse in the singular. In the past year, bolstered by the hubbub surrounding Facebook’s switch to Meta, a legion of metaverses have arisen to serve an audience geared toward expansion, capitalization, and the nonstop intrusion of big tech into the social lives of human beings.

Each self-designated metaverse contains a “spawn space” where every individual avatar entering that environment always starts. These spaces are clearly important areas of architectural inquiry, as they offer valuable insight into the underlying value systems that constitute them. They may or may not be designed by an architect (Zaha Hadid Architects recently designed a gallery for NFTs), but they are nonetheless “built” by open participatory communities. Their architectures, like everything else in the game environment, are designed to elicit the favor of or advance the aims of these communities. And so, in the spirit of inquiry, I decided to take the challenge head(set)-on. I bought a Quest 2 virtual reality system, hopped onto Twitch, and set off into today’s most popular metaverses. Here’s what I found.

Meta-Core

The spawn space for Meta’s Horizon Worlds (Facebook’s metaverse) looks like northern Arizona, complete with steep mesa walls surrounding an outstretched valley lined with palm trees and cacti. My perch is situated halfway up one of these mesa cliffs, in typical Frank Lloyd Wright fashion. Yet the surrounding structure is vaulted and curvy, more akin to the desert oasis Arcosanti, which Wright protégé Paolo Soleri conceived “as a deliberate critique of the rampant culture of consumerism.” But to my horror, the space seems to have been outfitted by the likes of Crate & Barrel: dome lights, throw pillows, tweed couches, yoga carpets, a gas fireplace, and otherwise extraneous “stuff” of contemporary life—exactly the opposite of DIY desert modernist ideal. Nothing about the interiors elicit joy in me, nor does any of it fit my vibe. This is all fine by Meta, which allows users to purchase, download, and upgrade their home environments to their liking. Hooray.

Cursed in the Afterlife

My visit to Horizon Worlds started off picturesque and wholesome: I dropped into a fun little shooting game and met a friendly someone who sounded like a child. After the game concluded, we were sent to yet another “lobby,” which is an actual space where avatars can socialize between matches. My friend giggled when I said I liked the low-poly trees—since for them the chunky conifer shape seemed obvious and unimportant. As we waited, my friend showed me how to complete routine tasks in the game, such as checking the leaderboard or tossing around a football.

But as soon as I stepped away to explore other areas and met some adults, everything became completely cursed. I was immediately catcalled. I reluctantly went to The Afterlife Club, a space oozing with lazy sci-fi tropes like illuminated hexagons and glowing node lights. I dashed toward the female-presenting robot bartenders, hoping for a glowing orange libation that looked like something from The Jetsons. A voice behind me offered to buy me a drink. I turned around to see four or five male-presenting avatars with masculine voices and was instantly bombarded with transphobic slurs. You see, I am a guy with long hair, and so is my Horizon Worlds avatar, but I’m shocked that that’s enough for some folks to judge me in the metaverse. I spent the next few minutes feeling powerless while watching this pack of ignorant bros harass any female avatar who came through the door. Last time I saw a seedy pack of men treat others like this, I was at a real-life club in Vienna and my raucous disapproval of their behavior landed me a night in the ER. This time, shock had frozen me in a way that filled me with embarrassment for not saying more—what were they going to do, kick my ass? This whole space must suck for marginalized people. Harassment of this kind is a well-documented issue within the metaverse and is at the same time extremely concerning and sadly predictable.

Less than ten minutes into the experience my adrenaline was pumping and I started feeling nauseated. I hit the metaverse ski slopes, thinking some fresh air might lift my spirits. As I rode the chairlift up a cartoonish hill with pop-up-book–like dimensions, I saw someone tumble off in front of me. I watched them intently, concerned for their incorporeal safety. Against all odds they found a high point in the slope and readied themselves to climb back onto the lift, their eyes focused on the empty spot next to me. As my chair neared, I tried to help them up, but the mechanics of the game were poor and unfamiliar to me. I accidentally took their poles from them and one by one threw them off the lift while shoving the person to the ground. How’s that for a pick-me-up? Feeling glum and fully sick to my stomach, I peeled off my goggles, had a big swig of (actual) beer, and ate a double ginger tummy drop. “What have I done?” I said out loud to myself, swirling in emotion.

Punk’s Graveyard

After recovering my sea legs and a shred of emotional confidence, I made my way to another metaverse called Decentraland, the “first fully decentralized world” of its kind. It is not owned by a corporation, but rather by its users: a group of similarly interested individuals who operate a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO)—basically a blockchain-based company. I began by hitting the Random button on the avatar generator, which spawned me as an unfortunate creature whose sock-and-trouser geometry collision wasn’t quite worked out, resulting in an unnerving glitch texture near my shins. It felt like wearing a shirt that needed ironing. Nevertheless, I and a handful of similarly costumed visitors found ourselves on a hilltop overrun with clouds in all directions, safely perched on a small patch of ground fenced in by three billboards resting aloft goofy Ionic columns. The billboards, which differed in height, advertised current events happening on the ground down below. In the center, a circular pool of water poured in on itself, similar to the aesthetic swirl of Anish Kapoor’s 2014 installation Descension except highly triangulated. A cheeky diving board dropped users directly into the center of the vortex—a strange choice, seeing as we did not expect to make a splash as much as get sucked in.

This could be a contemporary acropolis. We could have instant access to unlimited information instead of stone-faced structural columns. One needs only a browser and an internet connection instead of executing an arduous climb to the top of a hill. Yet rather than seeking wisdom, culture, or philosophy, here in Decentraland the quest is for coin and clout. This was reinforced by what I saw after jumping into the watery vortex: another piece of civic infrastructure designed after a bar (this one simply called Genesis Plaza Bar) filled with gaudy decorations of “line go up” meme culture—HODL, Musk, Doge, etc. Unlike the off-putting Afterlife Club, with its obnoxious slack-jawed chuds, this locale was empty and soulless.

I exited the communal space and made my way into the rest of the game world, which comprises multiple properties upon which any landowner can build whatever they want. And, yes, I mean landowner. You see, private property is taken to an extreme in this purportedly “free” space, which to me felt like walking through Europe in the Dark Ages: Accessing these fiefs requires specific types of NFT currency. Everyone is using a different currency and competing for your attention, trying to make ever more desirable experiences to sell to you, or simply to become the next viral meme. Even though property rights are already enforced through strict and impassable computer code, the presence of cop cars circling the map was a telling sight. How does one square calls for decentralization with the rampant valorization of existing power structures? How can something claim to be countercultural if it presents us with a laughably conventional, or just downright dreadful, version of the current world? Not exactly punk, is it?

Art in the Age of the Metaverse

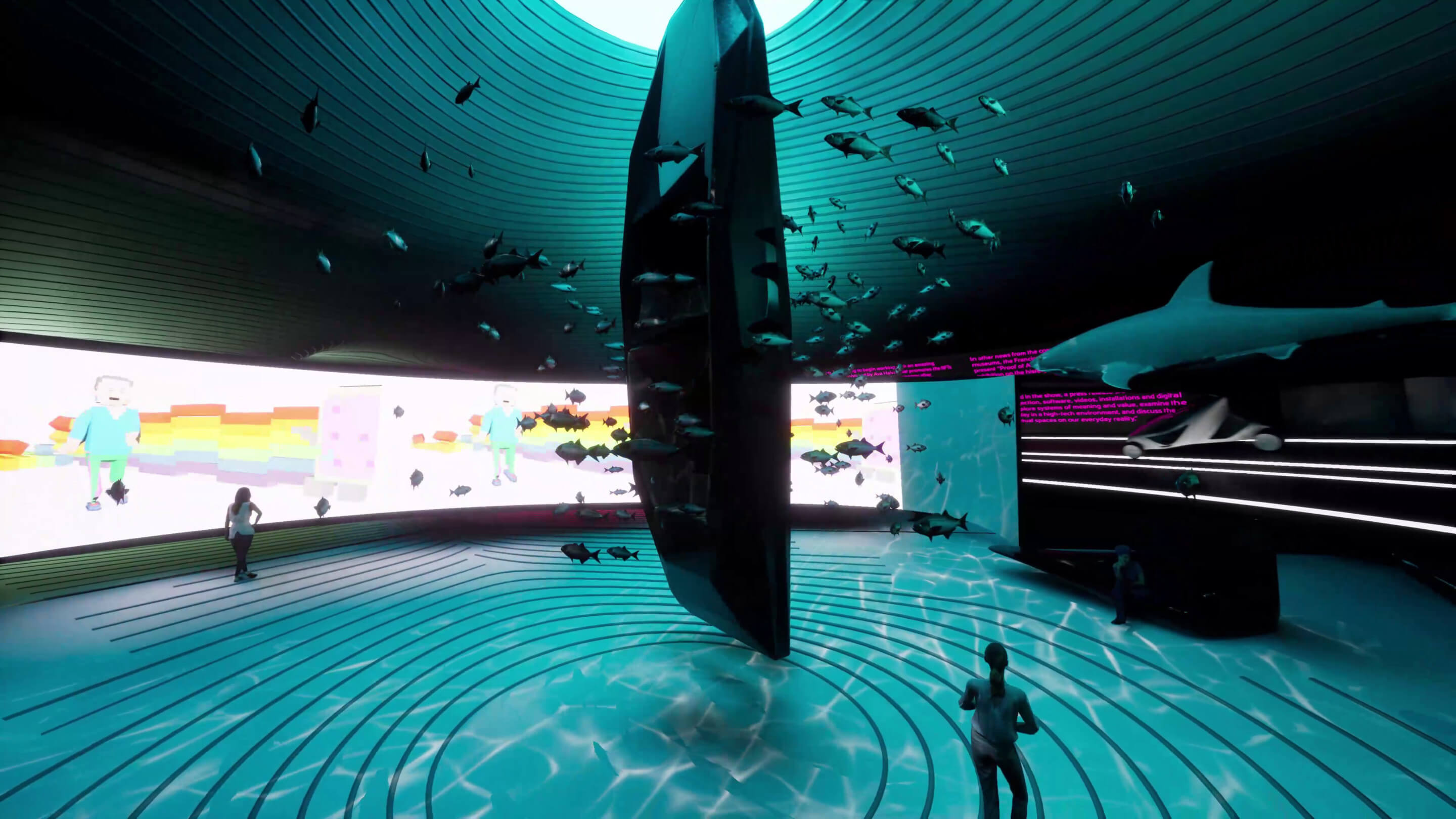

To close out my journey, I paid a visit to the Museum of Other Realities (MOR), a Vancouver-based virtual reality start-up designed with the help of VR artist Samuel Arsenault-Brassard. It was a welcome change of pace from the gamified social life I had just endured. While MOR doesn’t constitute the full ownership model of other metaverse spaces, it isn’t designed to take over your social life. It is a simple virtual reality art showcase—and it got me excited for the potential of 3D space in VR.

The forms of the structure were careening all around me. The artwork—made by artists with years of experience in the medium—was beautiful and vibrant. The scalar shifts filled me with joy, and the ability to edit my avatar by drinking different potions (à la Alice in Wonderland) put a monster smile on my face. This is what virtual space, art, and interaction could feel like if it weren’t designed to monetize every single interaction. Even in the metaverse, an art museum has real civic purpose, while the risks and spatial implications explored are a healthy balance of experimental spatial games with familiar spatial navigation. There are no exit signs, fire pulls, or even overhead light fixtures to get in the way of seeing this artwork. Even in the metaverse, what constitutes art is the same as it ever was: something called a museum and a wall label.

What are the right questions to ask as design professionals tackle future metaverse spaces? What is, and how do we define, a world? Of all the metaverses I visited, only MOR showed any hints of an answer. But generally, I suggest we remain skeptical of the next hyped NFT just waiting to be unlocked. Let’s be more like Frasier, who at the conclusion of “Door Jam” inveighs against the human compulsion for more. “Why,” he asks his brother, “must we allow the thought of something that to this point could only be incrementally better ruin what is here and now?” (To which Niles quips, with foolish yearning, “I don’t know. Let’s figure it out on the other side.”) At almost every step in the metaverse someone is trying to take advantage of our desire to be included. What lies beyond the next Porte d’Argent could be the next big thing, but it is way more likely to be hot garbage.

Ryan Scavnicky is the founder of Extra Office, a design studio that investigates architecture’s relationship to contemporary culture, aesthetics, memes, and media to seek new agencies for critical practice. He teaches theory, criticism, and architecture at Kent State University.