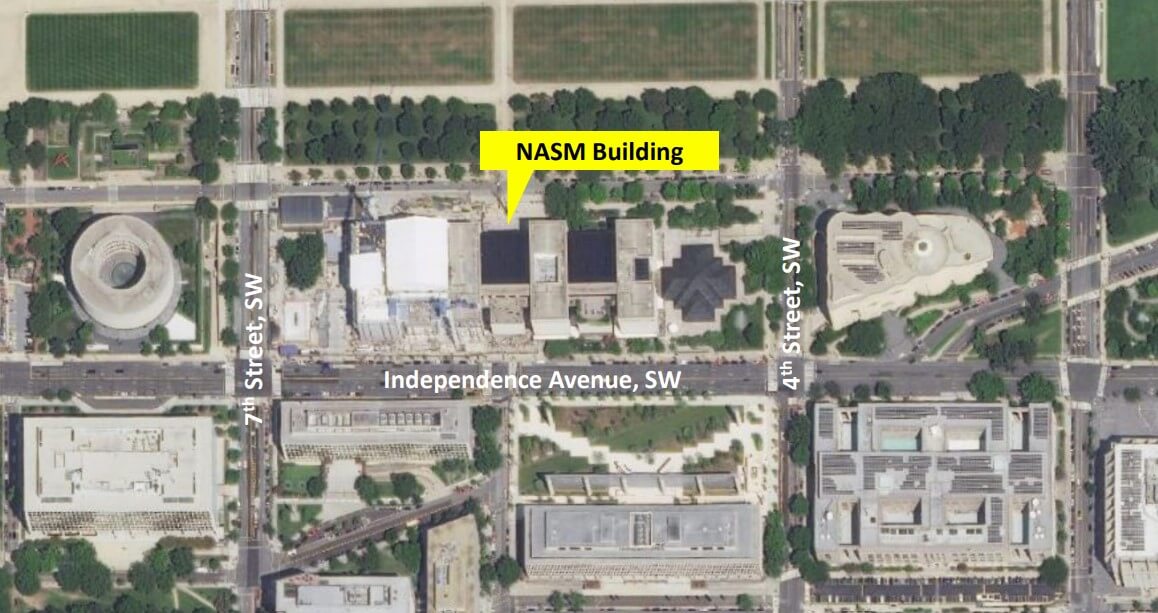

The Smithsonian Institution is preparing to tear down one of two buildings designed for the National Mall by the late architect Gyo Obata to make way for a new educational facility called the Bezos Learning Center.

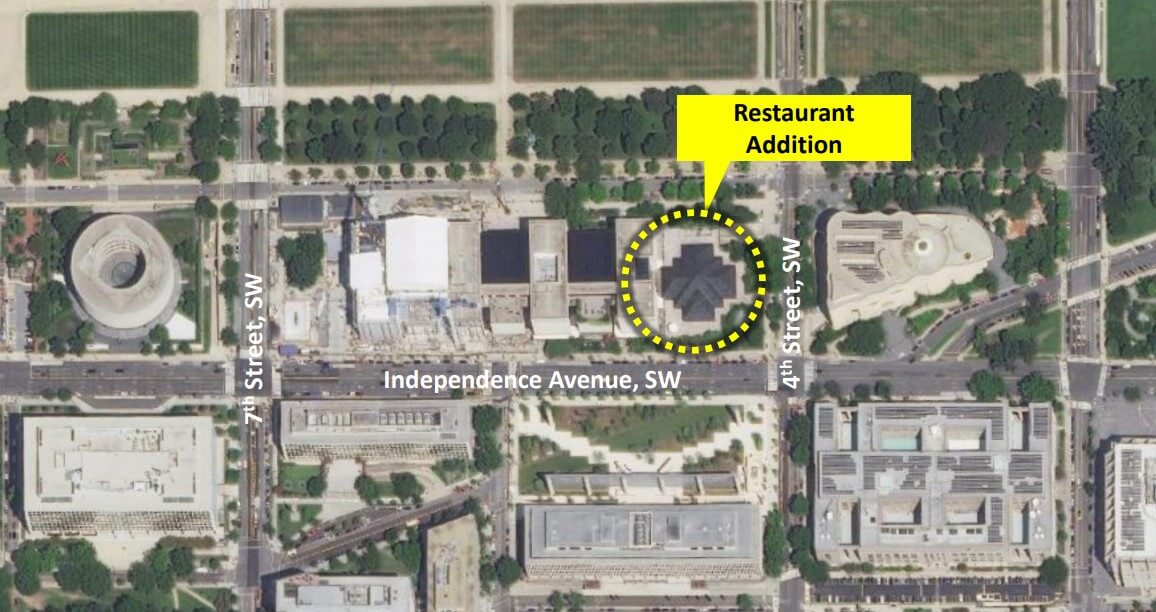

Smithsonian representatives recently told members of the National Capital Planning Commission and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) that demolition will begin this spring on the glass-clad restaurant pavilion that opened in 1988 as an annex to the 1976 National Air and Space Museum.

The pyramid-shaped pavilion was constructed largely to serve school groups and others attending the museum, one of the most visited in the United States, but it has been closed since 2017 and is not protected by any sort of landmark designation. Obata and his firm, Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum (HOK), designed both. The museum is currently closed for renovations.

The Bezos Learning Center is a three-story, 50,000-square-foot project made possible by a $200 million gift from billionaire Jeff Bezos, founder and executive chairman of Amazon and founder of the space flight company Blue Origin.

The Bezos building will occupy roughly the same footprint as the restaurant pavilion on the east side of the Air and Space Museum. The Smithsonian describes it as a world-class educational center featuring programs and activities related to innovation and careers in science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics. It will be connected to all Smithsonian museums, coordinating collections and experts across the Institution and promoting inquiry-based learning for visitors of all ages, with a focus on under-resourced communities.

According to Rick Flansburg, associate director of collections, archives and logistics for the Air and Space Museum, the Bezos building will contain a ground floor restaurant, two floors above for programs, and a rooftop terrace with views of the National Mall and the U.S. Capitol. The main entrance to the learning center will be from the museum’s second level.

The southeast corner of the site is likely to become the permanent home of the Phoebe Waterman Haas Public Observatory, now located on the museum’s southeast terrace, and the eastern edge of the site may become an outdoor astronomy park, planners say.

An architect has not been selected, and the Learning Center is a highly sought-after commission. The Smithsonian issued a solicitation for architects on January 18 and set a submission deadline of February 17. The Smithsonian is aiming to name an architect by the end of this year.

When Bezos’s donation was announced in July of 2021, leaders of the Smithsonian said it was the largest gift the Institution has received since James Smithson’s founding contribution in 1846, and that the building would be named after Bezos in honor of his donation.

According to the Smithsonian, $130 million of Bezos’s $200 million gift will be used to create the learning center—$80 million for design and construction and $50 million for programming. The remaining $70 million is going toward renovation of the nearly 604,000-square-foot Air and Space Museum, a project that started in 2018 and is expected to cost more than $360 million.

Marked by its four marble-clad pavilions separated by three glass and steel atriums, the Air and Space Museum spans four city blocks and cost $40 million to construct. Planners say it needed revitalization because certain building components were downgraded to keep construction costs low and have worn out. The renovation is being led by Quinn Evans Architects. The Smithsonian intends to supplement the gift from Bezos to demolish the existing restaurant, improve the museum’s loading dock, and build a new restaurant, observatory, and astronomy park.

In the 1980s, Obata, who died on March 8 at 99, was chosen to design the Air and Space Museum—a scope of work that included the restaurant in question—over other leading Modernist architects who sought the commission, including Kevin Roche and Gordon Bunshaft. Other key buildings designed by Obata include the Priory Chapel at Saint Louis Abbey in Creve Coeur, Missouri; the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport; the Bristol Myers Squibb campus in Princeton, New Jersey, and King Khalid International Airport and King Saud University in Saudi Arabia.

Carly Bond, a historic preservation specialist for the Smithsonian, said the Air and Space Museum is considered a contributing resource to the National Mall Historic District and is eligible for individual listing on the National Register, but the glass-enclosed restaurant pavilion is not.

She said the Air and Space Museum contributes to the historic district because it is a “significant historic building designed without precedent for housing a nationally important collection of artifacts documenting the history of flight and space travel” and represents the work of a “recognized master” in architecture, among other factors.

But “after careful evaluation,” she told the National Capital Planning Commission, “the restaurant addition was determined to be non-contributing to the historic significance” of the Air and Space Museum.

One group that has raised questions about the restaurant pavilion is modern architecture preservation advocacy group Docomomo US. Executive director Liz Waytkus told AN that her organization stopped short of taking a position on the Smithsonian’s demolition plan for Obata’s restaurant pavilion because it was hoping first to see the evaluation process revised and more information provided.

“Our organization’s position is that the Determination of Eligibility [for National Register listing] for the restaurant addition of the National Air and Space Museum is incomplete and has findings that are not in keeping with our understanding of the Secretary of the Interior standards for the Rehabilitation of Historic Places, and that additional energy should have been put towards understanding the restaurant and its significance,” she said.

Waytkus and Docomomo US vice president for advocacy Todd Grover said they believe the museum and the restaurant pavilion should have been evaluated as one project, not separately, because they both have the same owner, are physically connected, are on the same property, have the same entrance, and serve the same overall purpose. Docomomo US didn’t take a stand on the demolition itself because members thought it would be premature, she said.

“You can’t make a determination on demolition until you’ve done all your research. So we’re not weighing in on whether the building should be demolished or not, [or] whether it should be replaced, because they haven’t done enough research on its significance…It should have been much more in-depth about [Obata’s] career and this entire project and not just the restaurant alone.”

Docomomo also disagreed with certain findings in the Smithsonian’s report, Waytkus said.

“We didn’t feel the Smithsonian had done their due diligence on the significance of the restaurant addition,” she said. “They were arguing the restaurant is not functionally related to the museum…and that it was somewhat of an afterthought [but] the restaurant was always planned for that site and its construction was delayed due to the lack of funding. The restaurant addition is functionally related to the museum building and should not have to stand on its own in terms of determining its eligibility for the National Register.”

“We at Docomomo are often faced with a double standard for Modernism. We hear all the time that ‘we can only preserve one example of either some design or some designer. We can only preserve one of them. ’“You would never say of an earlier period or earlier designer: ‘McKim, Mead and White, oh, we have already preserved a McKim, Mead and While building. We don’t need any more.’ Or Frank Lloyd Wright. Honestly, we hear this all the time.

Waytkus also lamented the demolition from the standpoint of sustainability. “It’s not an environmentally-friendly thing to do anymore, putting buildings in dumpsters,” she said. “We need to be reusing the fabric we already have.”

Bond told the two commissions that the Smithsonian’s planners explored the idea of retaining and repurposing the restaurant building before and after the Bezos gift was announced, but concluded the existing building would not be able to accommodate the program envisioned for the Bezos Learning Center without substantial changes to create more square footage and address “building deficiencies.” Bond said the building is not energy-efficient and would be difficult to add onto or retrofit.

In terms of eligibility for National Register listing, she said, the restaurant building’s later completion date affects whether it’s considered to be a contributing element to the Air and Space Museum.

Bond said Smithsonian directors and others have drafted an agreement that governs how the project will move ahead. She said the agreement, among other points, calls for the Obata building to be documented for historical purposes.

She also noted Docomomo US was the one consulting party that raised questions about the preservation process. “They didn’t agree with our interpretation of the restaurant addition being separate” from the main museum and asked “how Air and Space is eligible for the National Register” and not the restaurant addition, Bond said.

One CFA member, Duncan Stroik, had recommendations for the design of the replacement structure.

Stroik said he believes there are two possible approaches to the design of the Bezos center: “One is to simply extend the fabric of the existing building, not unlike what was recently done at Dulles International Airport to Eero Saarinen’s work. Or to step forward and do something that’s really tremendously figural. This was done very successfully I think at the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art. It’s not one of my favorite buildings at all, but I think it’s a very successful example of what I’m suggesting to the Smithsonian Institution here.

The Smithsonian’s timetable calls for demolition work to take place this year; for 2023 to be devoted largely to design, and for construction of the Bezos project to start in 2024 and be completed in 2026, the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the 50th anniversary of the Air and Space Museum.