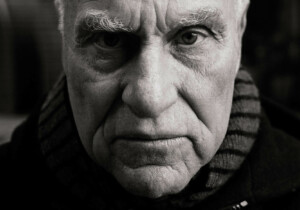

Dan Graham was inexplicable, and I often felt that he wanted it that way. He possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of many subjects (art, architecture, rock music, arcane details about the lifestyles of ex-presidents) but parsed the information with such unrelenting idiosyncrasy that conventional histories were usually shredded in favor of his telling. Once it was dispensed with, the comfort taken in the common notions of the past and present was replaced by the appeal of Dan’s fractured brilliance, flashes of convincing insight followed by assertions so ludicrous that you were sure he was fucking with you.

And I think he often was. His intellectual curiosity was enormous. A side effect of this insatiable appetite for engaging with not only art ideas but also the possible significance of a pop icon’s astrological sign was that the world around him probably seemed to move too slowly—and he needed to speed it up. Sometimes that meant direct challenges to accepted opinion with something so out of left field that it would both keep you guessing while maintaining your focus on Dan rather than the intellectual status quo that he loved to attack.

I had come to know Dan Graham the artist several years before I met Dan the person. I still remember my first encounter with his work, reading his “Corporate Arcadias” article in Artforum at the art school library, with clarity reserved only for those events that leave lasting impressions. If I returned there I could probably identify the spot I was sitting in when I read the piece. Taking what in most people’s hands would be dry subject matter (corporate architecture and gardens), Dan’s article was perhaps my first encounter with writing that was both playful and sharply critical, representing the possibility of an intellectualism unburdened by academic constraints or art world trends.

I eventually met Dan after moving to New York. Although it shouldn’t have surprised me, his outsize reputation within the field of contemporary art did not prepare me for his deep love of the absurd in everyday life (and commitment to highlighting it whenever possible) or the most convincing indifference to societal constraints I’ve ever encountered. While I had not been in New York for that long, there were aspects to its competitiveness that seemed to foster a kind of conformity, as though you had to calculate just how “far out” you could be as an artist but go no further lest you alienate those from whom you sought support. Dan would always go further, dispensing entirely with what most would consider appropriate behavior.

But he was neither antisocial nor asocial. The truth was that Dan was an incredibly social person, and his art was about creating space both for and about social engagement. While public art in America is often reliant on spectacle or aesthetically limited by “good intentions” (the former designed to seduce its audience and the latter to distract it from the decades-long neoliberal assault on the public sphere), at its best the experience of Dan’s pavilions embodies what he referred to as European socialism, an engagement with the public evident in a work by one of his favorite artists, Seurat’s Bathers at Asnieres, a space allowing for leisure in everyday life that might exist outside its relentless commodification.

One of the most poignant memories I have of Dan, a close friend of many years, is, perhaps oddly, from a Dutch architecture documentary he appeared in that had something to do with Rem Koolhaas being the next Philip Johnson. The main conceit of the film was to show famous architects a deck of cards one at a time and, in a solicitation into the machinations of power in the industry, ask who was the king, the queen, etc. When Dan was shown the deck he dismissed it with a wave of his hand, claiming that this exercise, like the quest for power in architecture, was a “stupid game.”

At another point in the film he’s shown entering perhaps his most impressive work in New York, The Rooftop Urban Park Project at Dia Chelsea. As he’s opening the rather cumbersome door that defines part of the cylinder at the center of the piece, he pauses to let a small child enter. While it could be seen as a somewhat innocuous moment and wasn’t at all central to the goal of the film, there was something striking about this engagement on the part of a person who’d just laid to waste the will to power in the architecture profession, shown within the site of one of his greatest achievements, pausing to yield to a little boy who seemed disoriented but thrilled at the place he found himself in. But that was Dan. He hated power but also had it. He would create controlled environments where much of what happened was out of his control. But most of all he was a very intense, brilliant guy who loved child’s play, and he went out of his way to do everything possible to facilitate it.

Peter Scott is an artist and the director of Carriage Trade Gallery in New York City.