On paper, the Focal Point Community Campus project in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood seems like a boon for the predominantly poor and multigenerational Latinx residents who live there. Spearheaded by Guy Medaglia, the project would build a new facility for Saint Anthony Hospital, which Medaglia heads as president and CEO. It would create acres of green space in a place where parks are scarce and build affordable housing where many now live on the margins. It would prioritize issues of public health in a neighborhood with tragically high rates of respiratory disease, resulting from proximity to an industrial and logistics corridor. Finally, it would put Saint Anthony, a safety-net hospital that has been a community fixture since 1898, on more sustainable financial footing.

But not everyone sees the development’s value as clearly as Medaglia does. Within Little Village, a painful eviction struggle and generalized fears of gentrification and displacement have made some wary of the project. Focal Point hasn’t fared much better at the municipal level. Although it was recently approved by the city council (groundbreaking is set for next year), it has attracted little meaningful support among local Chicago leaders.

Medaglia said that a better-equipped Saint Anthony and a larger campus through the Focal Point project can be a vital first step in carving out spaces for people’s mental and physical health. “Where there are residents, it doesn’t make sense for [the area] to be all an industrial corridor,” he said. “One hospital alone is not going to make the impact—neither is one campus. Focal Point is just the beginning of an overall plan.”

In 2012, Medaglia set up the Southwest Development Corporation (CSDC) nonprofit. He needed to replace Saint Anthony’s aging facilities but knew that financing a new safety-net hospital would be hard going. “We needed to get a little bit creative and come up with a different concept,” he told AN.

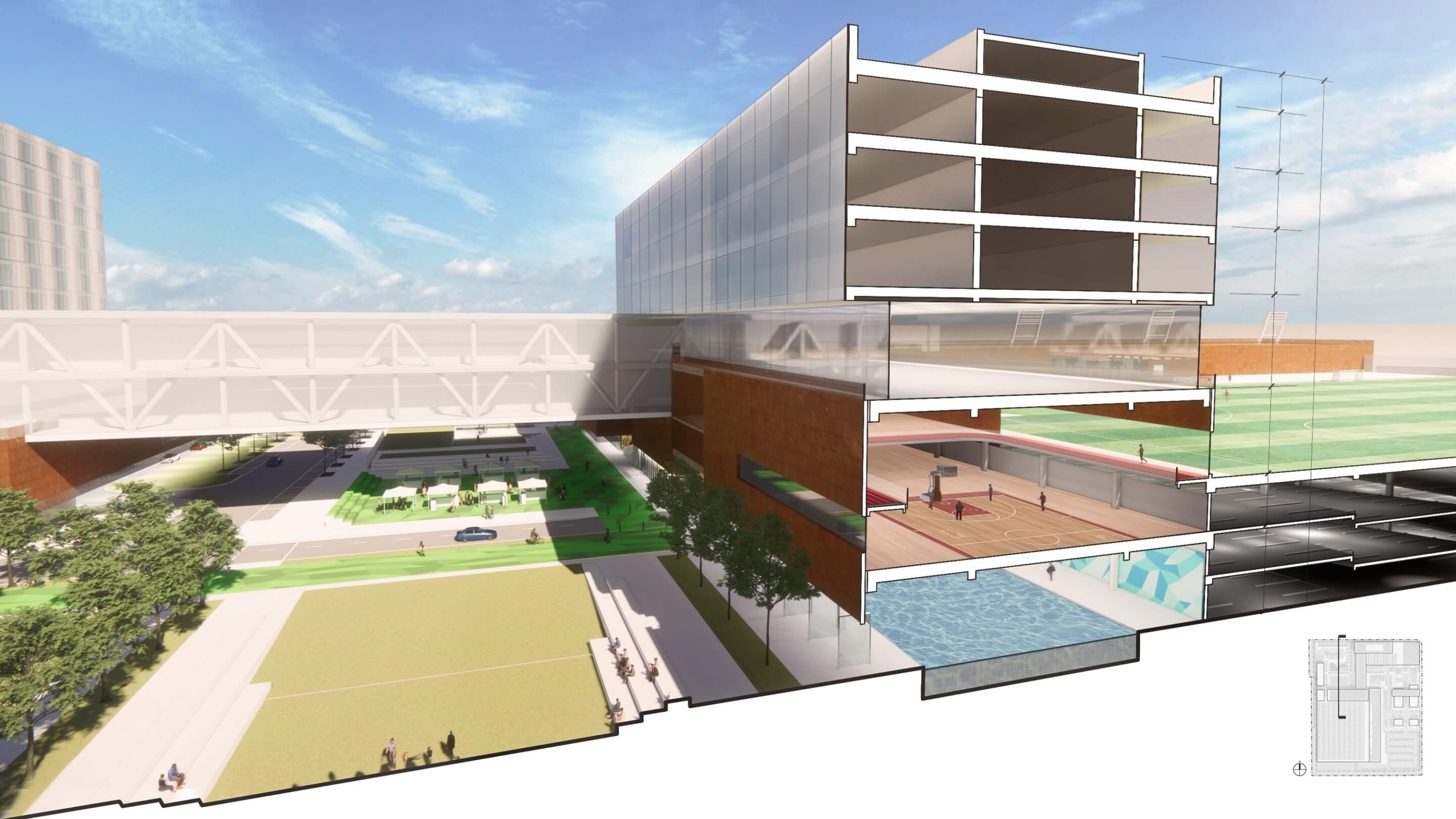

He tapped HDR to prepare a scheme for 32 acres of public land at West 31st and South Kedzie Avenue. The resultant plan divided the area into four quadrants. The northeast quadrant is given over to a new facility that would replace the existing Saint Anthony Hospital, set amid abundant park space and gardens. The northwest quadrant contains child-care facilities and 150 housing units, 30 percent of which, Medaglia said, will be tax credit–financed affordable units. To the southwest, the architects have imagined multipurpose sports fields atop a parking structure, while the southeast has been designated for mixed use (retail, offices, education).

Because job training is a key element of the Focal Point initiative, there will be an on-site trade school focused on the healthcare industry. Tom Trenolone, a design director at HDR, wryly summed up the programming as “half healthcare campus, half university campus, half city park.”

The stacked rectilinear buildings that he and his team designed attempt to blend in with the existing building stock. This would be achieved primarily through materials that change as the towers make their way skyward. Brick and Corten steel, which reference the neighborhood’s industrial heritage, appear closer to the ground, while glass takes over on the upper floors. A skywalk connecting the hospital’s acute-care and outpatient wings doubles as community meeting and event space. Its brawny truss supports nod to nearby canal bridges.

For Trenolone, the way Focal Point mixes programs within a consistent health and wellness rubric is unprecedented. “I don’t think there’s much out there,” he said. That is exactly what Medaglia was going for, but he admitted that the development’s experimental and nonprofit nature has put it at a disadvantage with investors. “I would have been better off as a for-profit corporation worth billions saying, ‘I want to put up a manufacturing facility.’ That would have been a lot easier. It’s so much easier to [get others to] believe in a for-profit organization.” (He is collecting corporate donations and borrowing money to finance the project.)

For a decade, Focal Point has lurched through site acquisition hurdles and municipal approvals. Despite its siting on the Southwest Side, it isn’t listed on the high-profile, $750 million INVEST South/West docket of projects looking to develop housing, transit, commercial corridors, and public services in some of the city’s most disinvested neighborhoods. The public funding that has been afforded to Focal Point—around $900,000 from the federal government—does little to chip away at its $700 million price tag. Other large-scale real estate developments with much more affluent people as their intended user groups have cruised through approvals and fundraising stages. For example, Sterling Bay’s luxury Lincoln Yards project on the wealthy North Side was handed $900 million of public funding. By comparison, Focal Point looks like an underdog, grassroots effort.

It isn’t, said Howard Ehrman, founder of Mi Villita Neighbors, a grassroots organization that focuses on community, political, and economic development as well as environmental quality. His family has lived in Little Village for more than 100 years. Ehrman believes Focal Point will usher in the type of gentrification and displacement experienced by the Pilsen neighborhood immediately to the east. He’s also leery of how much market-rate housing the project will deliver. “It’s a huge part of the project,” he said, adding that he’d like to know more details on how the housing subsidies will be tied to the area median income.

Ehrman called the potential redevelopment of a nearby discount mall and the El Paseo Trail (a rails-to-trails greenway project that’s planned to run by Focal Point) a coordinated effort to push out his neighbors. “That’s really the whole plan, to gentrify not just that part of the neighborhood but the whole neighborhood,” he said. “You’re not just only going to have the El Paseo Trail; you’re going to have this huge new project from Saint Anthony’s. People are going to move out in droves.”

Medaglia doesn’t think a development centered on a safety-net hospital will ever be a driver of gentrification, and he told AN he’d support a property tax freeze to mitigate risk to homeowners. “Saint Anthony’s will always take in the poor,” he said. “That’s the anchor.”

To that end, Medaglia devised a unique funding structure designed to reinvest in the neighborhood. Individual entities on site—including Saint Anthony—will pay rent to CSDC, through which a community board will disburse a certain amount of these funds (Medaglia estimates $7 million annually) to local nonprofits and institutions. It’s a better deal than most developers offer, he said: “Developers don’t do that. They don’t give away their money.”

Democratic alderman Mike Rodriguez is a supporter of the Focal Point plan and has endorsed a community benefits agreement for it. “Saint Anthony’s Hospital has been around longer than Little Village has been Little Village,” he said. “The Saint Anthony’s development project will help stabilize the community in many ways. It is very complimentary of our vision of preserving the Little Village community as the Mexican capital of the Midwest.”

When asked how Focal Point reflects the community’s needs and desires, Medaglia discussed a robust public engagement initiative going back years. CSDC set up meetings in high schools, churches, and supermarkets to solicit feedback. He said he relied on public health research from partners at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s College of Public Health, which assisted with the public engagement process.

But Ehrman said he’s seen people from outside Little Village bused in to community meetings by CSDC to forward its agenda. Medaglia clarified that Focal Point will serve people beyond Little Village and that he brought in people from adjacent neighborhoods who supported the project but did not have their own means of transport.

Carefully managing a public engagement process on controversial projects is familiar turf for HDR. An August 2021 Vice report revealed that the firm had taken on several jail and prison commissions and used surveillance techniques to keep an eye on its critics. The article details how HDR monitored public and private Facebook groups, analyzed public sentiment on social media platforms, used geospatial analysis, and created its own social media accounts at the behest of its clients. HDR later told AN, “Awareness of public sentiment helps us amplify all voices that need better access to public processes.”

The Focal Point site was the stage of a heated eviction struggle that ended last fall when a small group of Mexican American artists and musicians were removed on court order from one of the buildings in the area. CSDC filed eviction notices in February 2021 against Juan Herrera and Marcos Hernandez, and the artists vacated the premises in September. The HDR website touts a “center for creativity,” but Medaglia said they couldn’t find a way to fit these resident artists into future plans for Focal Point. “We tried every way to work with them in terms of moving forward with the project and helping them continue their artistry,” he said. (Multiple requests for comment from legal representatives of the evicted artists were not returned.)

Ehrman questioned CSDC’s and HDR’s commitment to local culture. He sent AN a slide deck presentation assembled by HDR and Saint Anthony Hospital for a medical industry event. One slide labeled “The Culture” depicted tattooed Black and Brown men throwing up gang signs overlaid on a photo of an abandoned building. “That’s what they think of the culture,” he said.

Trenolone, who says he didn’t assemble the presentation or take part in it, said that the purpose of the slide was to illustrate negative perceptions of Little Village’s culture outside the neighborhood, not to authentically characterize it. He called it a “lead-in slide for shock value” that segues into positive elements of the neighborhood. (The next slide is labeled “Success and Independence” and features a picture of Saint Anthony Hospital.) Trenolone also said that presenting these negative perceptions “might have been treated a different way if [the presentation] were given today.”

CSDC recently acquired an adjacent 11-acre plot that was once the site of the Washburne Trade School. Operated by the Chicago Public Schools from 1958 till the mid-’90s, the facility was demolished a decade ago. What Ehrman wants to see is a continuation of this legacy of public ownership—for the site at 31st and Kedzie to be controlled by a public entity with some level of democratic accountability, whether that’s a public trade school like Washburne, a library, or public housing. What’s important, he said, is that “every public space stays public.”

Zach Mortice is a design journalist and critic based in Chicago.