Through close observation and construction prowess, Stephanie Davidson and Georg Rafailidis elevate renovations into something special. “We’re interested in investigating spatial types not defined by use,” Davidson told AN—meaning not through program. For Rafailidis, that translates into championing values of “spatial character, definition, and specificity.”

The couple met while studying at the Architectural Association in London. Both were influenced by their time in Berlin, where they lived subsequently. Rafailidis studied the socialist-classical facades of Karl-Marx-Allee for a thesis completed under the late Mark Cousins, while Davidson worked under Judith Haase at the boutique studio Gonzalez Haase. In 2010, the couple decamped to Buffalo, New York, for academic appointments; Davidson now teaches at Toronto Metropolitan University, while Rafailidis is at SUNY Buffalo. They formalized their working partnership in 2012 after winning a design competition organized by the Storefront for Art and Architecture.

Once in the Bison City, they befriended a local microdeveloper, precipitating several commissions. Faced with the predicament of Rust Belt America, they began thinking of creative ways to use the scrap heap of available building stock around them. (A similar pileup of imaginative documentation is seen on their website, designed by Berlin-based graphic design studio Fuchs Borst.) “The buildings we’ve ended up working with have gone through crazy chapters,” Davidson said. “We’ve latched onto that history and, rather than try to suppress it, we learn from it and let it inform how we work. We want our interventions to allow for further unpredictability.”

Adaptive reuse interests the pair because “there’s a building that talks back to you,” Rafailidis said. “When we look at the built environment, it’s often used in different ways than anticipated. Buildings develop their own life, and it gives them a robustness to stand the test of time.”

He, She & It, 2016

A spiky addition behind an existing Buffalo home exaggerates mundane requirements to great effect. Three simple volumes, each with its own function (a greenhouse and studios for a painter and a ceramicist), intersect and create an intricate section. On the ground floor, folding walls reinforce connectivity—or separation—between the spaces. According to Davidson, she and Rafailidis wanted to avoid a too-tidy solution. “Rather than merging and negotiating the different spatial requirements in one volume, we ‘personified’ three mono-pitch sheds of similar sizes and collaged them together,” she said.

Big Space Little Space, 2018

This 1920 masonry back building once housed a taxicab repair shop. Davidson Rafailidis repurposed it as a residence for a downsizing couple who want a live-work space. Counterintuitively, the designers kept an existing partition and compressed the essential pieces of residential life into a small zone. They retained the exposed concrete floor, punctuated with drainage grates, and stained wood rafters. They also cut round skylights into the ceiling and perforated a weathered security shutter at the entrance with little circles; at night, the fixture is “a glowing moon,” Rafailidis offered. “The goal,” added Davidson, “was to respond to the idiosyncrasy of [our clients], without making it too imposing for the next owner.”

Together Apart, 2020

The name of this Buffalo cat cafe alludes to the spatial division of its plan. Building code requires spaces for food preparation and cats to be fully separate, but rather than erect a clear binary, Davidson Rafailidis installed a zig-zagging brick-and-glass partition. The solution created a compelling middle ground filled with details that blur zones, such as when terrazzo flooring masses into plinths that turn up into countertops. Even more curious is the backyard court, which “reads as an unfinished building,” Davidson said. “It’s structurally overdesigned so that it invites a roof, but that’s not part of the current design. It’s a very abstract trigger for what we hope will be continued construction on that deep lot.

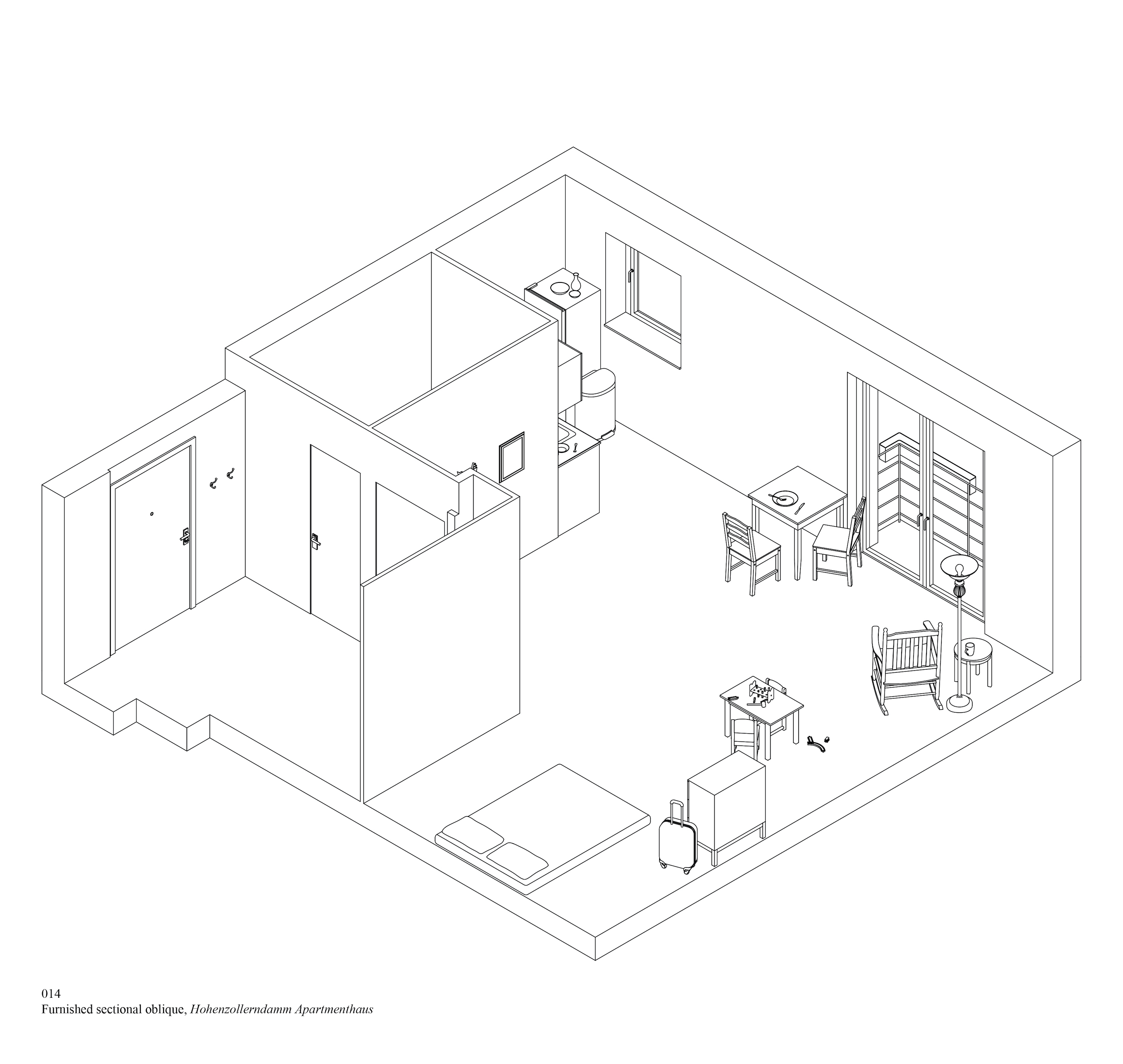

Drawing as Advocacy, 2022–

An ongoing research project with Mary Vaccaro, a PhD candidate in the School of Social Work at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Drawing as Advocacy focuses on the long-term needs of homeless women and gender-diverse individuals. Working from existing buildings, the renderings and drawings (made with Roxana Cordon-Ibanez) depict simple interiors furnished with household objects. Davidson said the initiative explores the idea of “space matchmaking.” “We wanted to pair these persons’ narratives with spaces that exist and draw them furnished with the objects and the appliances that they are wishing for, which are incredibly modest: a hot plate, a bed with a phone, or a door with a good lock,” she said.