The slow deconstruction of Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo began on April 12 and will continue through the end of the year. A curious public has been able to watch this process in near real time: Local crowds gather to pay their respects, and visitors from around the world snap farewell shots, with everyone sharing images on social media. Kurokawa was the youngest founding member of the Metabolists, a group of postwar architects in Japan who championed biological megastructures. Their “frantic futurism,” as described by Kenneth Frampton in Modern Architecture: A Critical History, resulted in only a handful of built works. The tower’s demolition is no surprise, as its problems were well known from the start. That it survived half a century is a feat in and of itself. Kurokawa showed us a version of a possible pod world that proved to be immensely influential, for better and worse. While we shouldn’t repeat the tower’s mistakes, its optimism about alternative futures is a legacy worth noting. To mark this moment, AN gathered remembrances in text and image from those whose trajectories brought them in close contact with the building.

Presented as a feature in the June 2022 print edition of The Architect’s Newspaper, these remembrances will run online as a five-part series, beginning with “Metabolic Memories” from Ken Tadashi Oshima, accompanied with photography by Filipe Magalhães and Ana Luisa Soares of Porto, Portugal-based studio fala atelier.

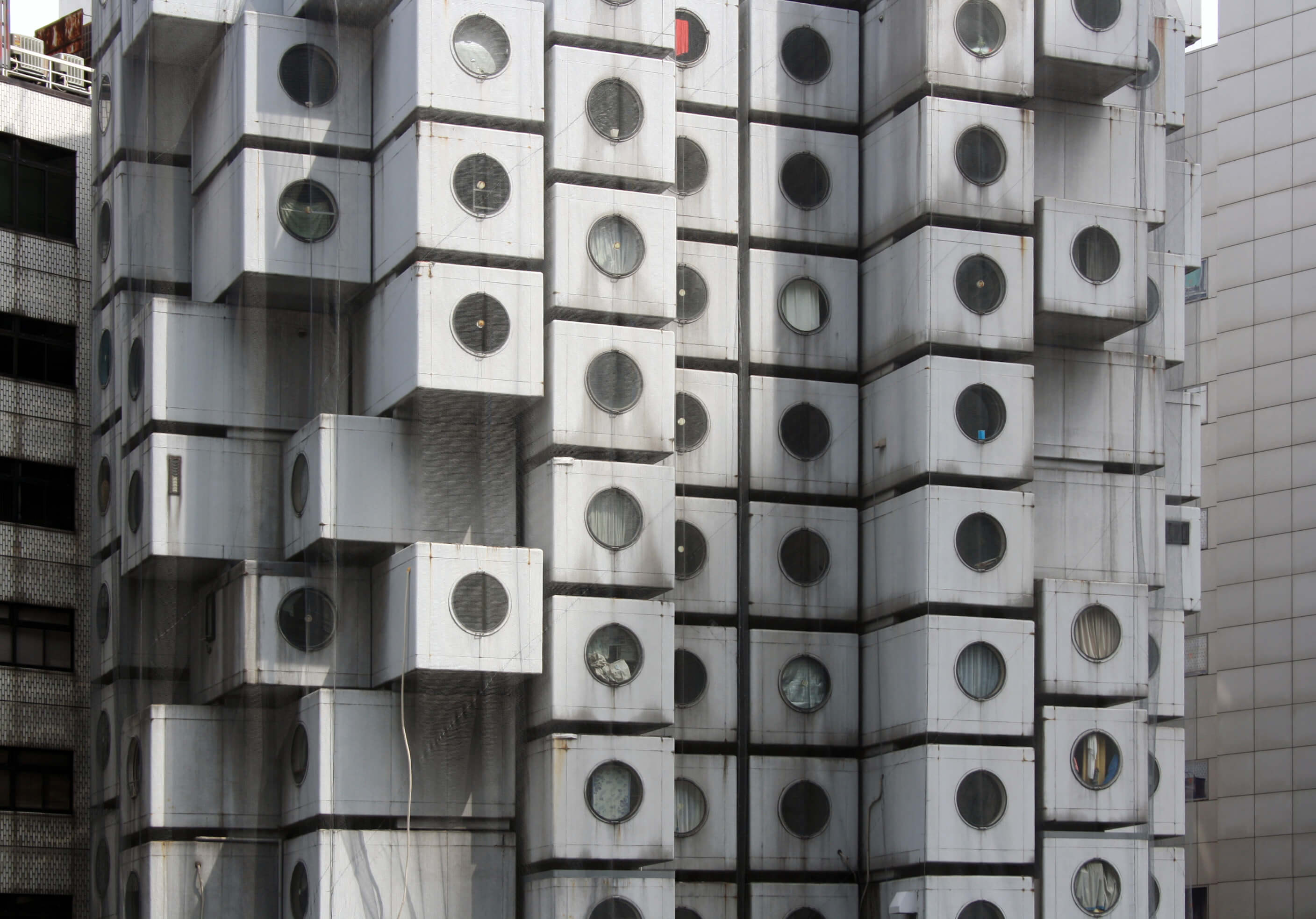

I first saw the Nakagin Capsule Tower during the summer of 1992, when I would pass by the iconic Metabolist work by Kisho Kurokawa (1934–2007) on my daily commute as an architectural intern in the Tokyo offices of the Takenaka Corporation. Twenty years had passed since the completion of the twin, 177-foot-tall towers, which comprised 140 prefabricated capsules, yet I looked with excited wonder into the large circular window of the model unit on the ground level; the interiors were furnished with super-graphic bedcovers, a Sony reel-to-reel tape player, and a Trinitron TV. I found it astounding that Kurokawa had helped found the Metabolist movement at just 26 years of age—just a few years older than I was at the time. The group boldly used the biological word metabolism, in the belief that “design and technology should be a denotation of human vitality,” as Kurokawa wrote in 1960. Here in front of me, I experienced the physical manifestation of his “future designs of (the) coming world” in this “concrete design” that he built at 38, which would become arguably the most notable design of his entire career.

From the outset, the Nakagin Tower stood within a “metabolically” transforming bayside urban district. The site was adjacent to the terminus of Tokyo’s first railway station, the former Shimbashi Freight Terminal, and elevated highways completed after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. With the onset of bubble-period development in the mid-1980s, the adjacent rail yards became the site of the massive Shiodome urban redevelopment. In the summer of 1992, it was still an open site used as an event space, covered by a massive circus tent, though this scene would radically change over the subsequent decade.

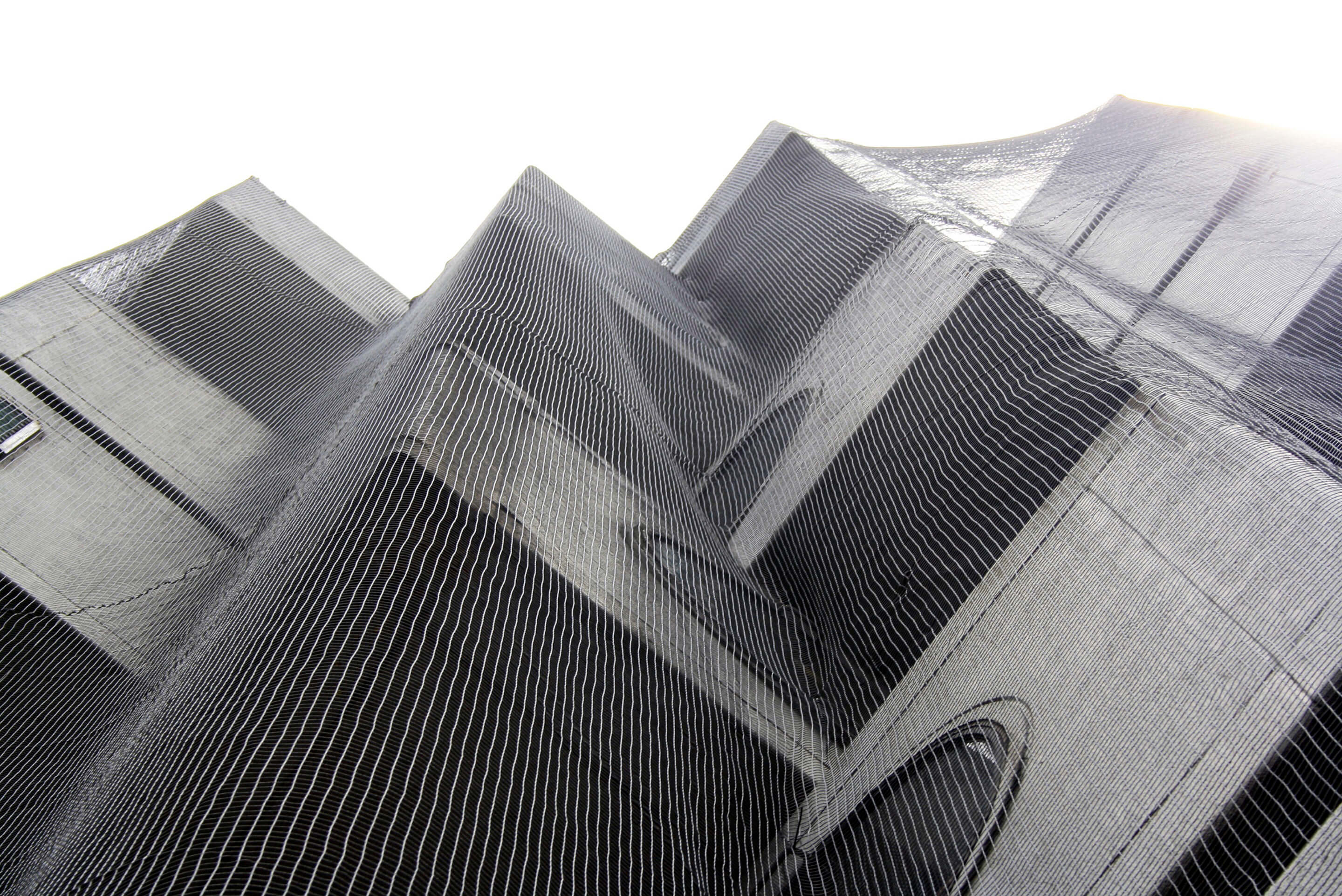

Kurokawa had envisioned the capsules to have a life span of 25 to 35 years and the tower some 60 years. Many of the surrounding buildings would end up having much shorter life spans or become radically transformed sites. In 2004, Takenaka moved its offices farther out toward Tokyo Bay, and its former tower was demolished to make way for a taller one, as building code limits evolved. The 48-story Dentsu Building Tower, designed by Jean Nouvel and Jon Jerde, was completed in 2002 on the open site in front of the tower; at 700 feet in height, it was four times taller than the Nakagin. Kurokawa’s Sony Tower building, which featured capsules the same size as those of the Nakagin Capsule Tower and was built between 1972 and ’76, was demolished in 2006, followed by Kurokawa’s own passing at 73.

Despite the constant changes in urban Japan between the 20th and 21st centuries, the original vision of the Nakagin Capsule Tower maintained its allure. A film capturing the factory fabrication of its capsules, crane assembly on-site, and a day in the life of one of its residents was featured in the 2008 MoMA exhibition Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling.

The continued maintenance of the units proved to be challenging and led to its eventual demise. In a 2009 New York Times article, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote that the building was:

a rare built example of Japanese Metabolism, a movement whose fantastic urban visions became emblems of the country’s postwar cultural resurgence, the 1972 Capsule Tower is in a decrepit state. Its residents, tired of living in squalid, cramped conditions, voted two years ago to demolish it and are now searching for a developer to replace it with a bigger, more modern tower. That the building is still standing has more to do with the current financial malaise than with an understanding of its historical worth.

In proving the longevity of Kurokawa’s vision, the capsule tower subsequently took on new life. While some units would simply become storage units, they captured the imagination of a new generation, including Tatsuyuki Maeda, who acquired 15 capsules starting in 2010, the year that hot water was shut off from the building. Nonetheless, those desiring a firsthand experience of capsule living could rent units through Airbnb, beginning in 2015, and the interiors of other units were transformed to accommodate uses varying from minimal home offices to tea ceremony rooms. Kurokawa himself translated the capsule ideal for his own teahouse villa, Capsule House K, completed in 1973 in the Karuizawa resort outside Tokyo, underscoring the broader historical trajectory of the capsule ideal. From 2018, the Nakagin Capsule Tower operated as a monthly capsules facility and offered some 200 occupants the opportunity to stay at the tower for weeks at a time.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic proved to be the final blow for the Nakagin. The owners collectively agreed to sell their units in 2021, and disassembly began on April 12 and will continue through the end of this year. From the outset, the Nakagin’s temporality may have been fated in its naive optimism through the use of materials like asbestos, originally thought to be a lightweight, fireproof material. Its use resulted in the enormous cost of some 2 billion to 3 billion yen ($16 million to $24 million) required for the tower’s renovation. While the original Sony Trinitron televisions and reel-to-reel tape players were emblematic of their conception as products inevitably to be replaced, the architecture also expressed its impermanence structurally: Each capsule was attached to the infrastructural towers using four bolts. While Kurokawa originally intended them to be replaced, they never were, owing to the complex realities of ownership and maintenance. Nonetheless, the original units may live on in new museum sites dispersed around the world and, perhaps most importantly, as manifestations of the constantly evolving ideals of Metabolism in which Kurokawa, writing in Japan Architect about the Nakagin Capsule Tower upon its completion, reconceived “the house as a community of individuals living in new innovative ways.”

Ken Tadashi Oshima is a professor of architecture at the University of Washington, where he teaches transnational architectural history, theory, and design. He is the author of many books, including International Architecture in Interwar Japan.