According to the photographic record, the lot at 443 East 142nd Street in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx was once occupied by a quaint (if unremarkable) Queen Anne–style row house, indistinguishable in almost every detail from the ones on either side. So it appears in the tax archive from 1940; by the time of the 1980 edition, the building—and indeed the entire row—is gone, leaving nothing in its place except a garbage-strewn dumping ground. The two pictures constitute a sort of capsule history of the whole neighborhood—or at least of the received history of the South Bronx, the oft-told tale of a spirited working-class enclave that descended into urban mayhem after midcentury.

But there’s always more to the story. A filmmaking mecca in the 1910s; home to artisanal workshops in the 1930s; and, even following its decline in the 1970s, a key redoubt of the city’s immigrant community and the birthplace of contemporary street culture: The borough’s southern-most area has never been short of vitality. The trick now is preserving it. “Obviously the South Bronx has seen an influx of people and of investment lately,” Patrick Bonck, assistant vice president at affordable-housing provider Breaking Ground, told AN. “That’s a good thing. But not if it means displacement of the people who have always lived there.”

Breaking Ground’s latest project is an attempt to prevent that. Enter the Betances, the new senior-residence building that now stands on East 142nd Street, a 152-unit subsidized housing complex built as part of a collaborative effort between Bonck’s nonprofit organization, the New York City Housing Authority, and the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Just opened this month, the project provides older Bronxites with low-cost apartments as well as on-site care facilities and programming, all in a building with a surprising degree of design flair and a particular sensitivity to its historic surrounds. “We wanted something that would make the people living here feel like they were really part of the neighborhood,” said Jared Gilbert, associate partner at COOKFOX Architects.

The firm’s collaboration with Breaking Ground has arrived at a key moment. The travails of those seeking housing in New York City are well publicized; less so are the challenges faced by older residents, some 200,000 of whom were stuck on waiting lists for federally supported housing as recently as 2020; the number has likely risen during the pandemic. The problem is especially acute in the South Bronx, where pre-pandemic data shows not only that senior poverty rates are above the citywide average but also that they are growing year over year.

At the same time, Mott Haven and the adjacent Port Morris neighborhood are currently witnessing the most intense gentrification in the history of the borough, with the $1 billion Bankside luxury-apartment complex now wrapping up construction on the Harlem River waterfront. For older Bronxites, many of whom lived through the area’s roughest years, the influx of bars, restaurants, and shops could be a long-awaited boon—but not if there’s no place left for them to live. “If a neighborhood changes, people want to stay and enjoy it,” says Samuel Stein, a housing advocate with the Community Service Society of New York. “Unless you have affordable housing, people will be very skeptical of those kinds of improvements.”

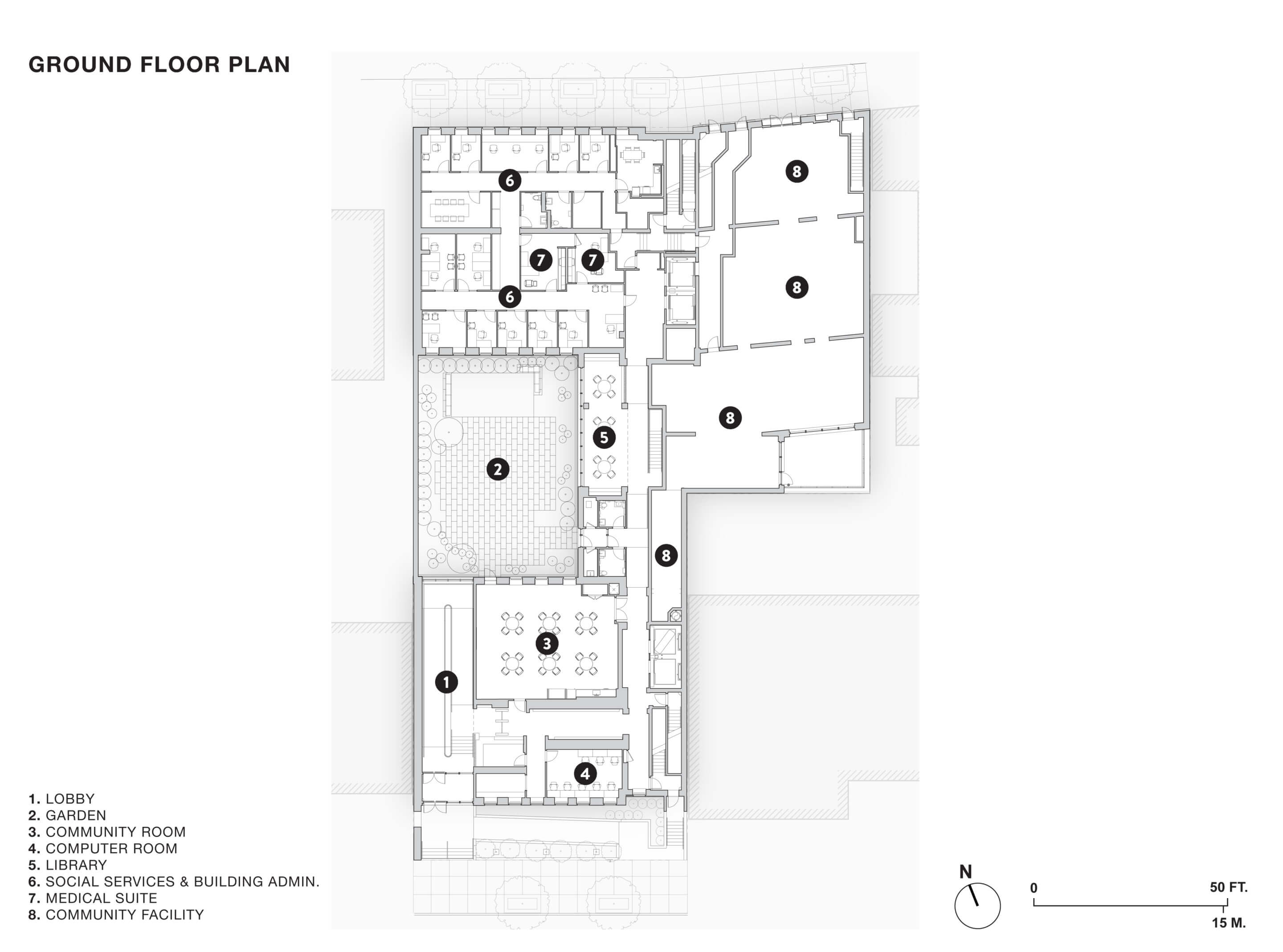

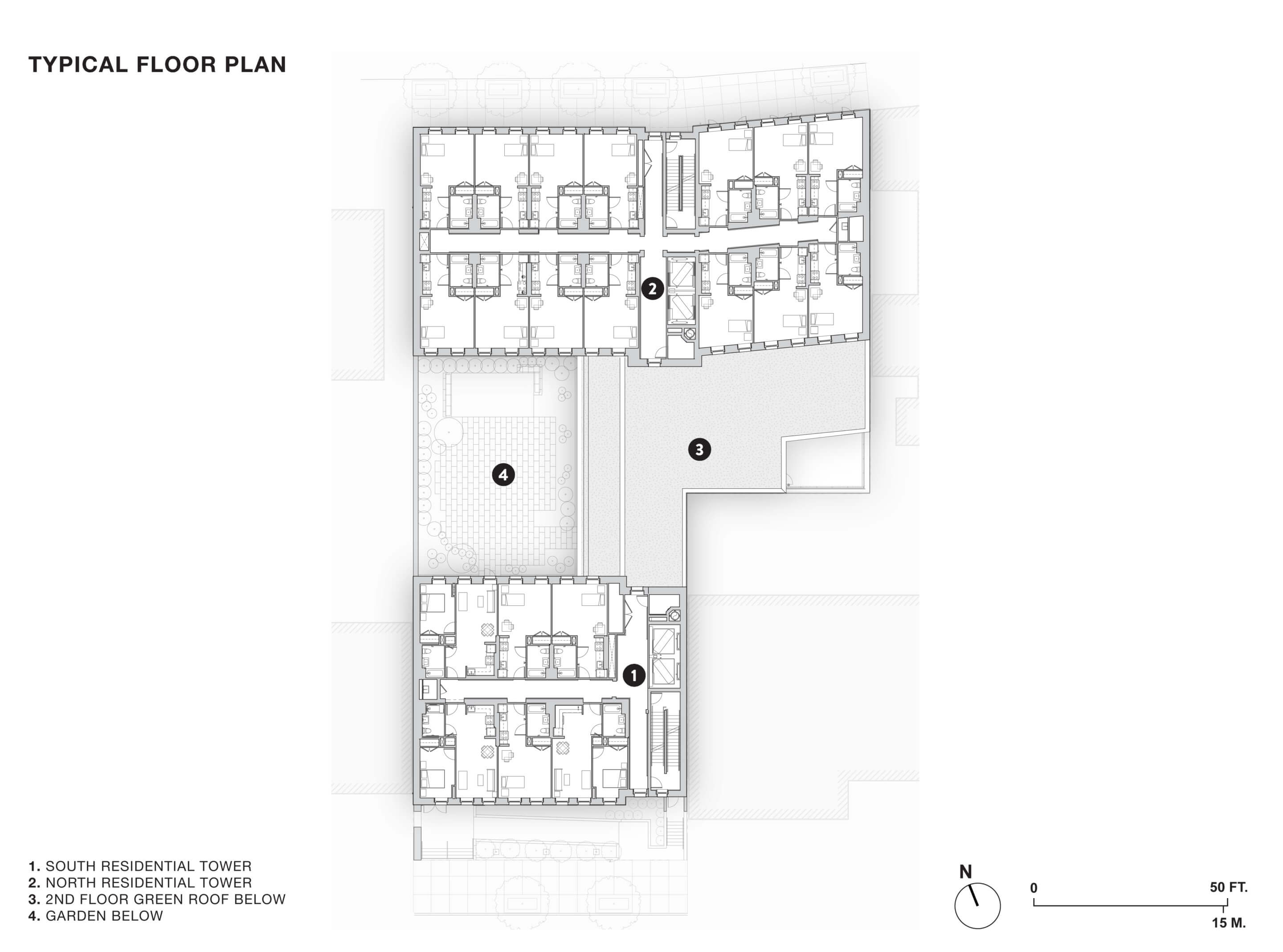

The Betances represents a concerted effort to keep the Bronx’s most-tenured residents in the borough. On the 20,126-square-foot site, which spans 142nd (also known as Piccirilli Place) to 143rd Street, the project follows a barbell plan, with two 8-story towers on either frontage, linked by a narrow cross-block connector. This gallery-like volume, containing a small reading room and topped by an accessible green roof, runs along the eastern perimeter of a courtyard garden, fronted to the south by a space for community events and to the north by an on-site healthcare facility. On the outer elevations, upper floors clad in dark metal paneling sit atop a brick base, while on the inner elevations, the banded brick covers the surface’s full height. The individual dwellings, mostly studios but also some one-bedroom units, are comfortable and smartly appointed, with sweeping views as far as Queens and the Midtown skyline on the southern side. More important is the feeling of connectedness to the Betances’s immediate urban environment: The backyards of the neighboring houses are visible from the garden, the welcoming landscaped entryway ramps up to the front door, and the mottled brick facade complements both the old-law tenements and the newer two-story infill buildings that surround it. Everything seems geared to keep seniors from feeling boxed in or sealed off. “Even the elevator vestibules are daylit,” notes Darin Reynolds, senior partner at COOKFOX, who led the project.

On a recent visit, residents had just begun to move into their new apartments, making their way slowly up and down the sloping interior walkway that leads to the 24-hour doorman and dedicated package room. “I wish my apartment building had that,” Gilbert said. Indeed, there’s a lot to envy at the Betances, which boasts a host of features one might expect from a far more upscale address. Topped by solar panels on the south tower and sporting serious insulation and all-electric appliances, the building has received the coveted passive-house seal of approval, landing it at the very cutting edge of energy efficiency; the rating is a point of pride for the project’s designers, but it provides a tangible benefit to its inhabitants as well: “We were able to provide residents with very high indoor air quality [and] to create very quiet living spaces,” says Reynolds, pointing to the sophisticated filtration and circulation systems as well as to the triple-glazed windows that keep out the street noise.

Perhaps COOKFOX’s greatest design accomplishment is how little this low-cost, nearly net-zero housing development looks like either of those things: The finishes and fixtures in the below-grade lobby wouldn’t be out of place in a boutique hotel, and even the acoustic paneling in the gallery is turned to aesthetic effect, setting up a pleasing rhythmic procession through the corridor. As the South Bronx undergoes yet another one of its serial transformations, the Betances is a welcome sign that this time, with any luck, the old neighborhood and the new one might be able to coexist.

Ian Volner has contributed articles on design and urbanism to The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic, among other publications, and is a contributing editor at Architect and Architecture Today (U.K.); he is the author or coauthor of numerous books and monographs, most recently Jorge Pardo: Public Projects and Commissions 1996–2018 (Petzel, 2021).