The office of John Friedman Alice Kimm Architects (JFAK), situated in an old brick warehouse just off the 4th Street Viaduct on the east side of the Los Angeles River, is a bright space with a baby grand piano in one corner. The instrument, which Kimm and one of her employees who happens to be classically trained occasionally play, would seem to be a symbol of the firm’s professed architectural philosophy. Friedman told AN: “Alice and I both carry a deep love of pure design, but with a desire that our architecture make the city better and [people’s] lives better. That intersection has really been important to us from the beginning. It’s an intersection of playfulness and seriousness.”

This conceptual pairing is evident in the firm’s houses, which, broadly, construct functional yet expressive space and appear carefully attuned to natural light. The duality of playful and serious is also an ethos the two feel they share with L.A. culture, especially show business. Friedman continued: “The movie business, for one thing, is storytelling and playful and ad-lib, but it’s highly technical, highly structured, and organized.”

Friedman and Kimm started their practice shortly after arriving in L.A. in the early 1990s. At the time, they felt like outsiders. Both had studied at the Harvard Graduate School of Design under then chair Rafael Moneo, and Friedman had worked for Álvaro Siza. Like all good transplants, they talk about their adopted city with an infectious boosterism: Kimm remarked that the can-do culture fosters a mindset that declares, “Innovation is accessible.” This pride of place has steered the firm’s trajectory. “Right now, a lot of our work is focused on the civic realm,” noted Kimm, “and that’s really important for us, because of our belief in the power of architecture to change people’s lives and strengthen community.” In L.A., making civic architecture today means making space for social services, most notably to address the needs of the city’s large population of unhoused and housing-insecure residents. This critical work constitutes much of JFAK’s portfolio lately.

Casa Namorada, 2018

One great thing about L.A., Friedman said, “is you’ve got ranch style next to modern next to Tudor next to Mediterranean. That’s part of the charm.” To wit, this private home in Santa Monica sidles between its neighbors with confident verve. A protruding light-box window and quarter-round volume cantilevered above a bright yellow garage door all gesture to the street yet reveal very little. This swooping public face of privacy befits the plan, in which the entrance is through a side court concealed behind the front gate. That “front” door opens to a double-height formal living room with calibrated natural lighting from skylights and the aforementioned window. At the back, the kitchen and family living room spill out into the yard, and the home, transformed into a picturesque indoor-outdoor dwelling with an abundance of filleted surfaces, becomes something else entirely.

Navig8, 2021

This publicly funded navigation center in South L.A. provides services to unhoused neighbors. Constructed using prefab modules, the center comprises restrooms, showers, personal storage, a laundry, job training classrooms, and offices. Set back from a broad avenue, the building owes its presence to its second story—significant in these low-slung plains—and a pergola that extends to the sidewalk. Visitors queue beneath its undulating canopy, which matches the colorful stripes that adorn the boxy building in a pattern of interlocking gables, an icon of home upright and inverted. “Like poetry or film,” explained Friedman, the shape can be “interpreted in multiple ways.” Kimm added: “I think it’s an important marker of how cities can treat these types of service buildings. They could really help change the public perception of homelessness by giving a little bit more love to these types of projects.”

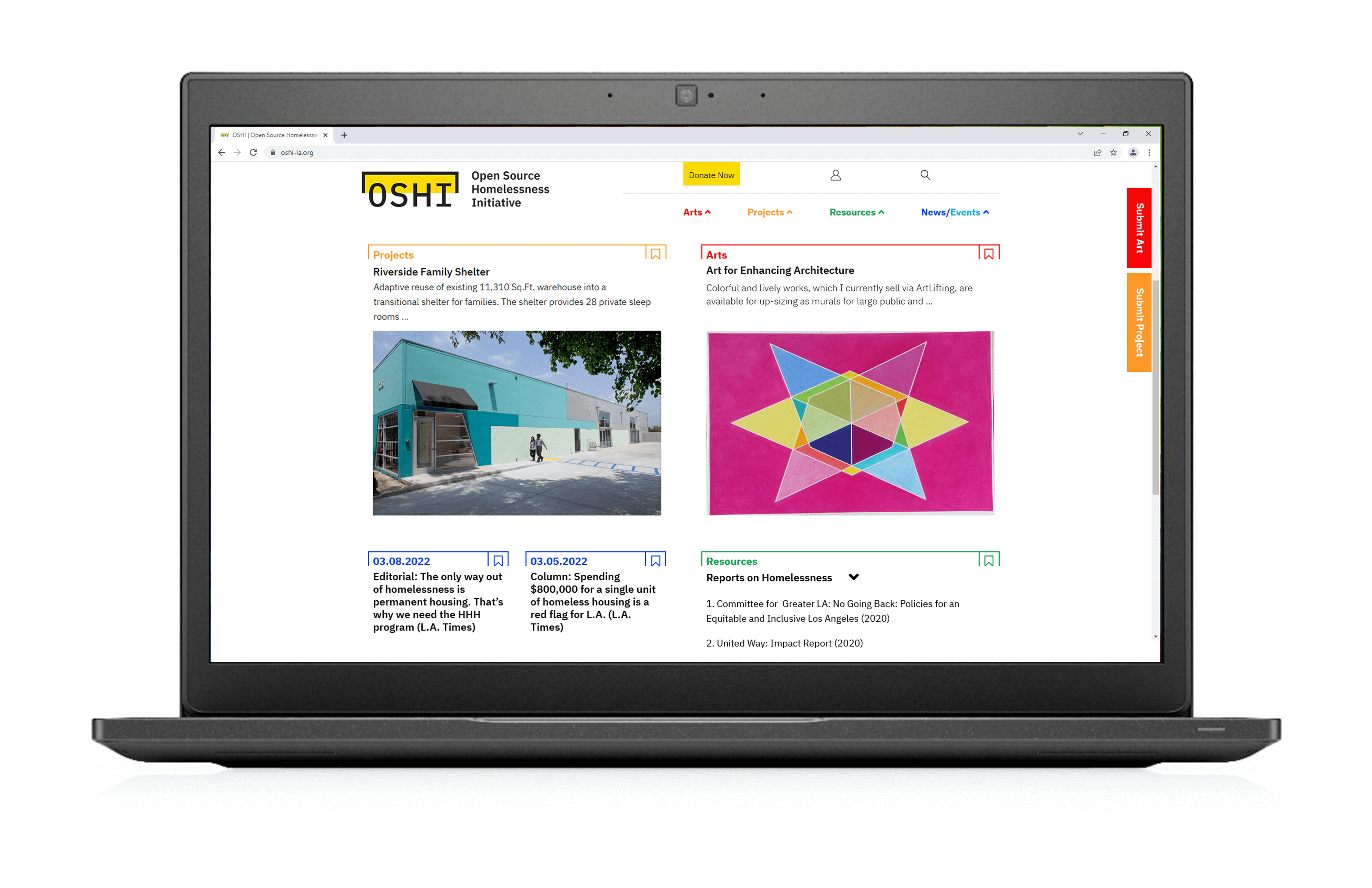

Open Source Homelessness Initiative, 2021–

During their work on the Navig8 project, Friedman and Kimm were struck by a dearth of connection and knowledge sharing among the many entities working on the issue of homelessness. Launched last year, OSHI aims to offer a database of news, resources about organizations and funding, and project case studies, including buildings as well as art produced for and by unhoused people. True to its open-source nature, the site is a pragmatic, nonpolemical resource. “Ultimately, our goal is to accelerate solutions,” said Kimm. She continued: “The boundaries of architecture are not fixed, and to me, all the architectural thinking that goes into making something like this work is just as valuable as another project.”

Westbrook Academy and Community Center, 2022–

This South Gate campus is a project for the LA Promise Fund and NBA star Russell Westbrook’s Why Not? Foundation. Anchored by a new 80,000-to-100,000-square-foot community center, it also includes a middle and high school in an existing warehouse and a third building with a daycare, a community kitchen, and a cafe. These programs are tightly packed into a site bounded by a boulevard and a freight railway. “There’s very little pedestrian access,” Friedman noted, “but you take advantage of that, and you say, ‘Well, now we can build up to [the street] and use it for frontage.’” Above ground-level parking, the trapezoidal floor plates of the community center are stacked askew, making the most out of their cantilevers. In classic L.A. style, these shifted boxes are skinned in vertical louvers that form screens of text readable from passing cars.

Luke Studebaker is a writer and architect living in Los Angeles.