Edward Hopper’s New York

Curated by Kim Conaty with Melinda Lang

Whitney Museum of American Art

New York

Through March 5

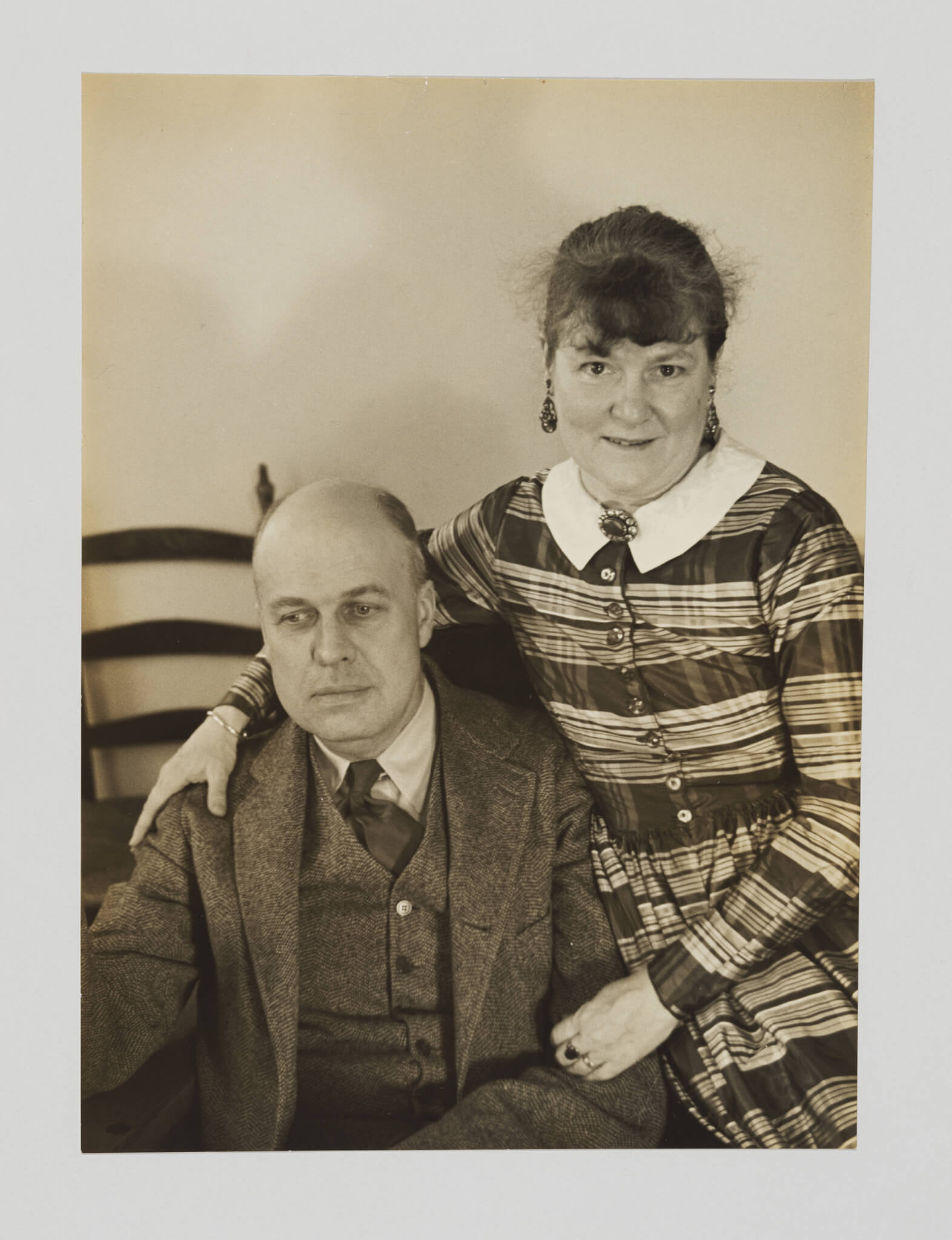

Urban flaneurs will enjoy roaming Edward (and Jo) Hopper’s New York at the Whitney, an exhibition staged by curator Kim Conaty to “emulate that exploratory experience of moving around the city on your own.” The spacious, spare installation features over 200 city-focused works, drawn largely from the museum’s authoritative collection and organized by theme in rough chronology. Well-known paintings (with unfortunate omissions, such as Nighthawks [1942]) are complemented by numerous studies and contextualized through compelling documentary material from the Whitney Archives and Library (including the controversial Sanborn Hopper Archive) and other sources. Aficionados can even follow in the artist’s footsteps using a Google map seeded with paintings and a few documentary images.

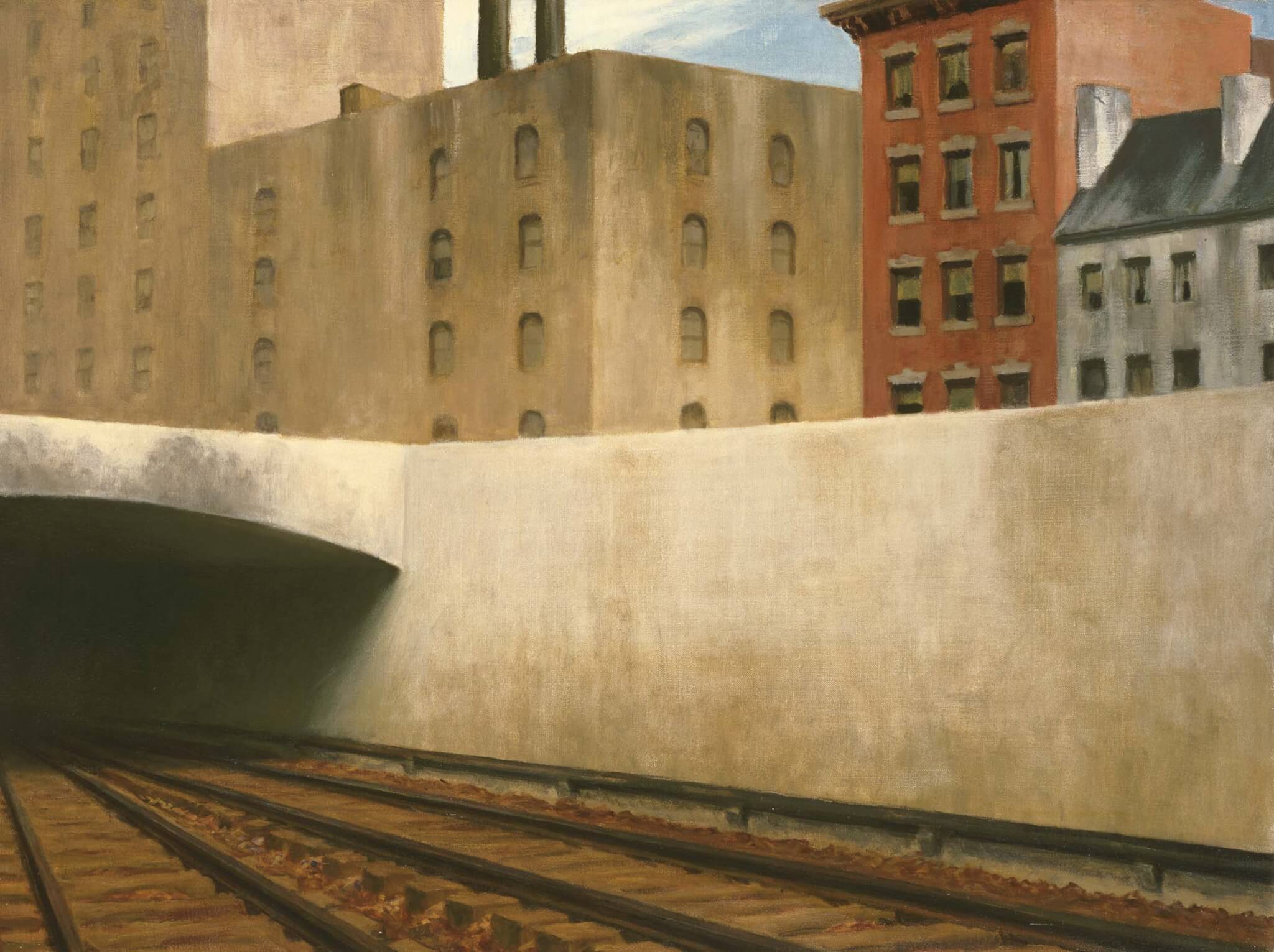

The show is formally introduced by the painting Approaching a City (1946), its dark tunnel a vivid metaphor for a boy from Nyack plunging into the big city. As a child, Hopper visited on family outings, and as a student, he commuted by ferry to the New York School of Illustration and New York School of Art, precursor of the Parsons School of Design. Exhibition visitors emerge, like the artist, in the thick of Manhattan. An eclectic assembly of early works evoke the young Hopper’s early encounters with the turn-of-the-century city. Pen-and-ink sketches of people, from train conductors to acrobats, are especially evocative.

The City in Print section highlights Hopper’s underappreciated commercial career of at least two decades. A generous selection of magazine covers, advertisements, and etchings demonstrate Hopper’s narrative focus, compositional clarity, and reproducibility—qualities also seen in his paintings.

A city resident by 1908, Edward moved to 3 Washington Square North in 1913. From there we see the view From My Window (1915–18), see a birds-eye perspective of The City (1927) with Hopper’s 19th-century rowhouse, a Second Empire edifice, and an encroaching modernist tower compressed into view. Several roofscapes complete the scene. City Roofs (1932) for example, references the early Village high-rise One Fifth Avenue, completed just a few years prior.

In the darkened Theater section, a row of annotated ticket stubs brings us along with the Hoppers on their regular attendance at live performance. Here famed works such as New York Movie (1939, his only painting of a cinema) are further contextualized by sketches of Jo, appearing in the role of model, and illuminating documentary photographs from the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, including set designs by unexpected figures such as architect Joseph Urban and designer Norman Bel Geddes.

In subsequent sections we follow Edward down side streets (Sketching New York) and up into elevated trains (Windows). We venture to the edges of Manhattan, looking north to the Bronx in Macomb’s Dam Bridge (1935) and Apartment Houses, East River (c. 1930), then east to Queensborough Bridge (1913) and Blackwell’s Island (1928), and also south to Manhattan Bridge (1925–26) and Brooklyn Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928).

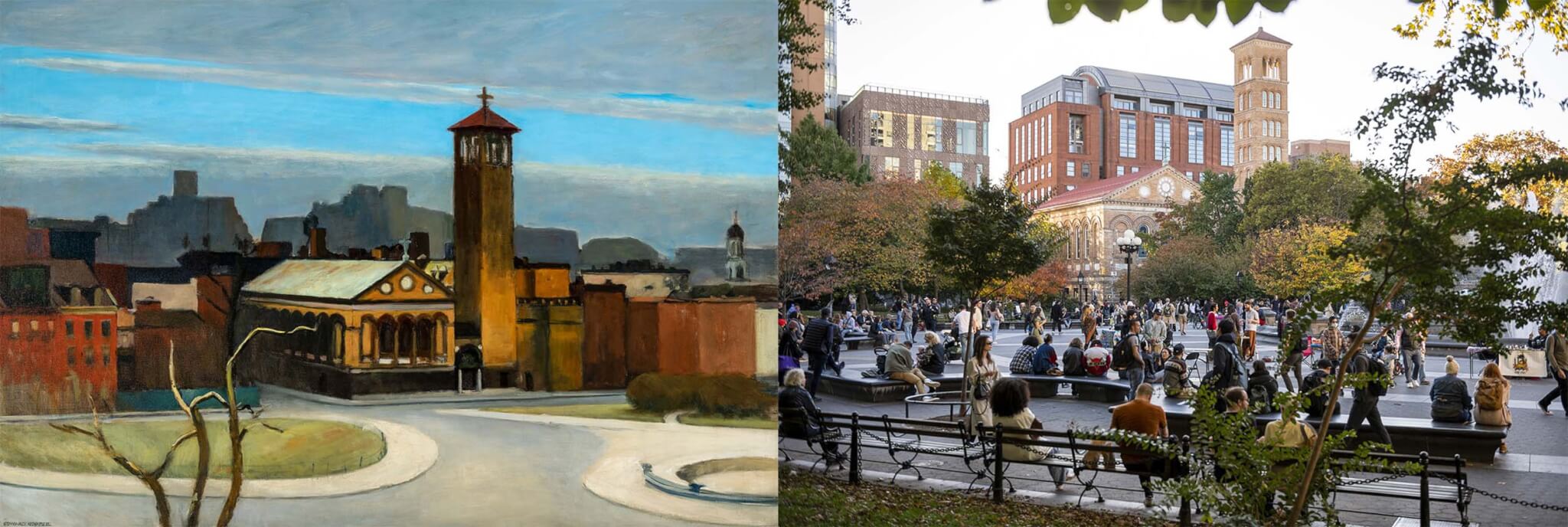

Our vicarious tour ends back at Washington Square, where the Hoppers lived and worked for the rest of their lives. They had to fight for it, though. When rapidly expanding New York University threatened eviction, Edward appealed to an unsympathetic Robert Moses, then City Parks Commissioner, as seen in pithy correspondence on view. NYU lost the subsequent court battle in 1947 (evinced by reassuring 1965 footage of the senior couple in situ) but ultimately won the war through attrition. Today the townhouse is one of three forming NYU’s Silver School of Social Work. Ironically, the Hoppers’ top-floor studio has been preserved and can be visited by appointment.

The Hoppers crossed paths with Moses again in the 1950s, as they closely followed his plans to run a highway through the park. In the painting Washington Square (c. 1932/1959) we suddenly notice a nondescript service road winding around Stanford White’s Washington Square Arch (completed 1892) towards Judson Memorial Church (McKim, Mead & White, 1888–96), and imagine the massive construction that could have been.

Jo is most present in the Washington Square gallery, where three watercolors of studio life hint at her perspective. Serving as Edward’s model but also his manager, archivist, and advocate came at a cost to her career, one that deserves further attention.

We exit Hopper’s New York through a gallery titled Reality and Fantasy. Here the artist’s famed solitary figures strut their hour on his imagined urban stage, as seen in Office in a Small City (1953) and Sunlight on Brownstones (1956). As the curators point out, Hopper’s view was highly selective, with little interest in the mobilized masses of WPA murals and jostling crowds celebrated by Ashcan School painters. To today’s viewer, these venerable works may also evoke the pandemic-era empty city, as well as the way Hopper’s sharp urban light cuts out density and difference. With this in mind, the culminating gallery, framed by Renzo Piano’s double-height window wall, reveals an elevated view of contemporary New York now seen with additional appreciation. A glimpse of the revived High Line reminds us of the area’s dynamism, from the replacement of Moses’s West Side Elevated Highway with the thriving Hudson River Park to the harsh reality of luxury real estate to

Jennifer Tobias is a scholar and illustrator based in New York City.