In 1922, a competition to design the headquarters for The Chicago Tribune gathered influential entries from architects like Eliel Saarinen, Walter Gropius, Adolf Loos, and Bruno Taut. Despite the strong showing from modernist European architects, New York architects Raymond Hood and John Mead Howells were awarded first place, and their neo-Gothic design and an accompanying printing plant opened in 1925 on a site where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River. The skyscraper quickly became a key part of the city’s skyline and architectural imagination: In 1980, Stanley Tigerman staged a series of “late entries,” and in 2017 Johnston Marklee commissioned a set of new proposals for the Chicago Architecture Biennale.

One hundred and one years since the first sketches of the Tribune Tower, the winds of fortune have shifted. A slew of office-to-residential adaptive reuse projects have swept through downtown Chicago, turning historic buildings like the Century Tower and the entire stretch of the LaSalle Financial Corridor into luxury apartments; the Tribune Tower is the latest entry in this trend. The newspaper sold the building for $240 million to CIM Group in 2016 and moved out in 2018. Now the tower has been converted into luxury condominiums which range in price from $700,000 to over $7 million. The project, which includes 162 units and 55,000 square feet of amenity space, was completed by Solomon Cordwell Buenz (SCB). The architects aimed to preserve as much of the existing infrastructure as possible. This goal was derived from both respect for the historic significance of the site and from a civic mandate: The tower is a Chicago-designated landmark. Working closely with preservation architects Vinci Hamp Architects, SCB went beyond simply maintaining the tower, and made minimal interventions in the adjacent printing plant, radio building, and TV building; the latter two were built in 1935 and 1950, respectively. The entire complex helps shape the bustling public plaza of Pioneer Court, and SCB concluded that the essence of the Tribune Tower’s significance included all the buildings, not just the iconic tower.

SCB’s economical decision to keep the complex almost entirely intact won them the bid for the project. The primary design move at the scale of the site was to carve out a central section of the TV building to create an interior courtyard, accessible only to residents, and to add four stories of residential space to the northeast side of the building. This move effectively translated the demolished square footage vertically and opened up the massing to provide shared green space, increased natural light for the individual units, and private balconies.

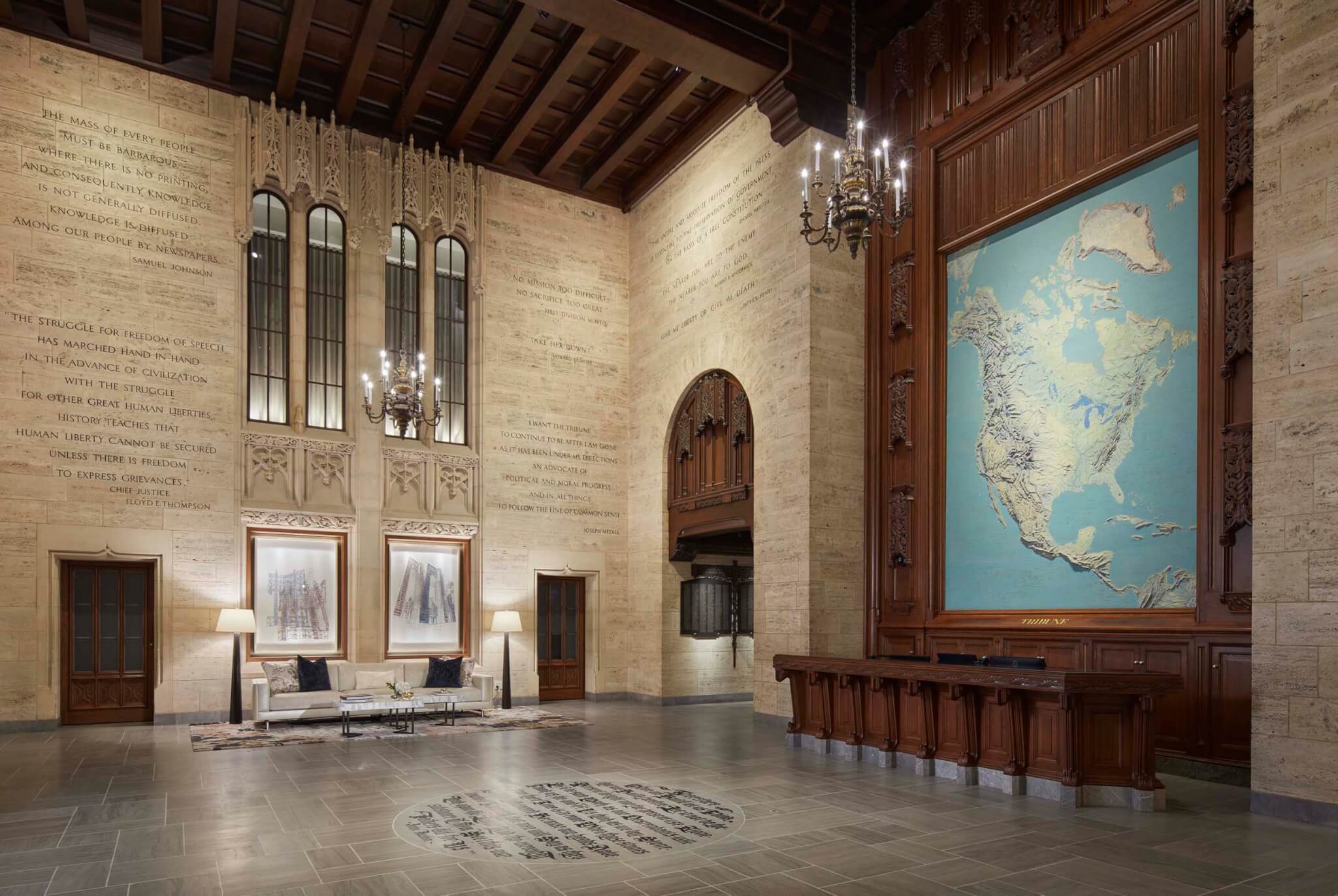

As the public encounters the building, the exterior remains virtually unchanged. SCB President Chris Pemberton described the goal of this approach as, “You walk by this when it’s done and think, ‘Well nothing really happened. It’s all the same.’” The bulk of the work took place in the interior as to update infrastructure like mechanical and electrical systems and to accommodate new programming like first-floor public retail, a private parking garage, a swimming pool, a fitness center, a lounge terrace, a herb garden, and a mini putting green. Interior details were also preserved to retain the character and significance of the historic architecture, ranging in scale from the entire tower lobby to intricate ironwork on the elevator doors.

Despite the sprawling size of the overall project (the total square footage clocks in at 950,000 square feet), the units themselves are carefully arranged to establish a residential scale. They range from one- to four- bedrooms and are configured almost entirely without hallways or vast expanses of open-plan living. Instead, the rooms are clustered in arrangements that fluctuate between communal and private and are dimensioned by numerous tall, narrow windows, characteristic of neo-Gothic architecture. The effect almost erases any notion of previous industrial use (in part of the complex) and happily blends historic details with contemporary finishes. Pemberton notes that designing units that felt appropriately scaled was important, but it was also a geometric imperative: The floor plates and structure of the existing building made the creation of large, cavernous spaces almost impossible. Even the shared common spaces, which residents can reserve for parties or meetings, feel like intimate living rooms and kitchens as opposed to a lobby or grand hall. This spatial orchestration is complemented by the work of the interior design team, The Gettys Group, who installed a variety of furniture configurations and low, adjustable lighting to personalize and differentiate the communal areas.

The most unique spaces in the building are its outdoor terraces, which bring residents in close contact with the iconic attributes of the tower. The pool and sunbathing terrace occupy a roof on the seventh floor situated directly behind the prominent Chicago Tribune sign. (The sign was removed while the terrace and pool were constructed, then replaced with reinforced structural integrity.) Residents can gaze out between the massive letters at the river and city beyond. It’s a striking setting of historic signage now repurposed as a backdrop for outdoor luxury.

Further up on the 25th floor, the crown of the tower itself serves as an outdoor area for grilling, lounging, and enjoying 360-degree skyline views. From what was previously an interior observation deck, residents can slide open glass doors and step out amongst the ornate stonework. This portion of the tower looks delicate and fine-spun from the street level, like a literal piece of intricate jewelry. The terrace offers a very different perspective, as the massive stone arches and flying buttresses spring from the floor within arm’s reach, shaping the seating areas in the nooks of the undulating spires. In the evening, the stone glows thanks to spotlights strategically mounted on the flying buttresses for the benefit of both residents and the city at large.

SCB’s efforts not only restored the past for present enjoyment but ensured that the building would remain a vibrant part of Chicago’s architectural menagerie for years to come. As such, the stone edifice was not only cleaned and repaired to flaunt its previous pale glory but also structurally reinforced to ensure that it would remain standing for another 100 years.

Alaina Griffin is a regular contributor to AN.

A prior version of this article incorrectly listed the crown level of the Tribune Tower. While the building has 34 floors, the outdoor area is on the 25th floor.

- Architect: Solomon Cordwell Buenz

- Location: Chicago

- Interior design: The Gettys Group

- Historic preservation: Vinci Hamp Architects

- Exterior lighting design: Schuler Shook

- Landscape design: Site Design Group, Olin

- Structural engineer: TGRWA

- MEP: Elara

- Vertical transportation: Jenkins & Huntington

- Exterior enclosure: WJE

- Facade restoration engineer: Klein & Hoffman

- General contractor: Walsh Group

- Developer: CIM Group, Golub & Company