François Dallegret: Beyond the Bubble 2023

Organized by Justin Beal with Kara Hamilton

Yale Architecture Gallery

Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

Through May 22

François Dallegret is best known in the architectural world as a sideman. His claim to fame was one notable collaboration with Reyner Banham: “A House is Not a Home,” designed for Art in America in 1965, a well-tempered vision of an all-mechanical residence enclosed not by walls but by a vaporous bubble. The image fomented many of the inflatable visions that ballooned up in the years to come. Yet there’s much more to know, and now much of it is on display at François Dallegret: Beyond the Bubble 2023.

Dallegret was born in Morocco in 1937 and raised in France. After he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, his life took several left turns. He turned to art from the start, with gallery splashes in spells in Paris and New York before he went north to Montreal, drawn by the prospect of commissions for Expo 67, where he’s lived ever since.

The exhibit is an expansion of GOD & CO, a 2014 show at the Architectural Association in London, with new material assembled by curators Justin Beal and Kara Hamilton. Some of the new content is especially large: A pop art car model (the Tubula), an “automobile immobile,” hangs from the gallery’s ceiling (after 55 immobile years in a Quebec barn). Other elements were gleaned from simply going over to Dallegret’s Montreal home. The exhibit features drawings of astrological automobiles, space cities, sculptures, chairs, posters, and all sorts of photographs—everything from manure-pile art installations to a smoking machine—silkscreens, and much more. It is tremendous fun.

Prior to landing in Canada, in the mid-1960s Dallegret contacted Jean Lipman, then-editor of Art in America, offering his services. Lipman then connected him with Banham. The pair were clearly kindred spirits, and the infamous piece seemed something of an exquisite corpse, with Dallegret working off of Banham’s initial text, and Banham then providing additional captions. One example:

With very little exaggeration, this baroque ensemble of domestic gadgetry epitomizes the intestinal complexity of gracious living–in other orders, this is the junk that keeps the pad swinging. The house itself has been omitted from the drawing, but if mechanical services continue to accumulate at this rate it may be possible to omit the house in fact.

Banham featured Dallegret in his 1976 Megastructures, and while it’s reasonable to class him with the Archigram-to-Superstudio mod set of the era, his particular emphases were often different.

Dallegret definitely drew up vast, absurd plans: See his Space City and Relationpublicomatic and Litteraturomatic machines (neologisms are everywhere), which look realistically plotted until you notice captions for “refrigerateur d’enthousiasme” and “beaujolais.” But most of his work was human-scaled or explicitly smaller in size. If much of the other avant-garde proffered large-scale visions and trusted that something interesting would happen within them, Dallegret was most frequently occupied in devising exactly these sort of granular, liberatory things.

There’s a Cliclacrocotartomatic, a farcical contraption presented in a series of drawings. Dallegret’s drawing text reads, “This machine, the invention of which joins purity of intention and technological simplicity, is a veritable mobile with three motor units. It allows slaps, pie throwing, tripping and even kicks in the ass. Here at last we have the automatic de-complexer.” Got it?

There’s Astrological Automobiles: Detroit is not designing a model for your sign, Dallegret was. Much of his work fixated upon the human figure, often his own; photographs of himself are omnipresent, often attached to or within his own creations. Show organizer Justin Beal told AN that he was interested in this wearable technology: “It was something Dallegret was thinking about a lot, how technology would change the body’s interface with the world.”

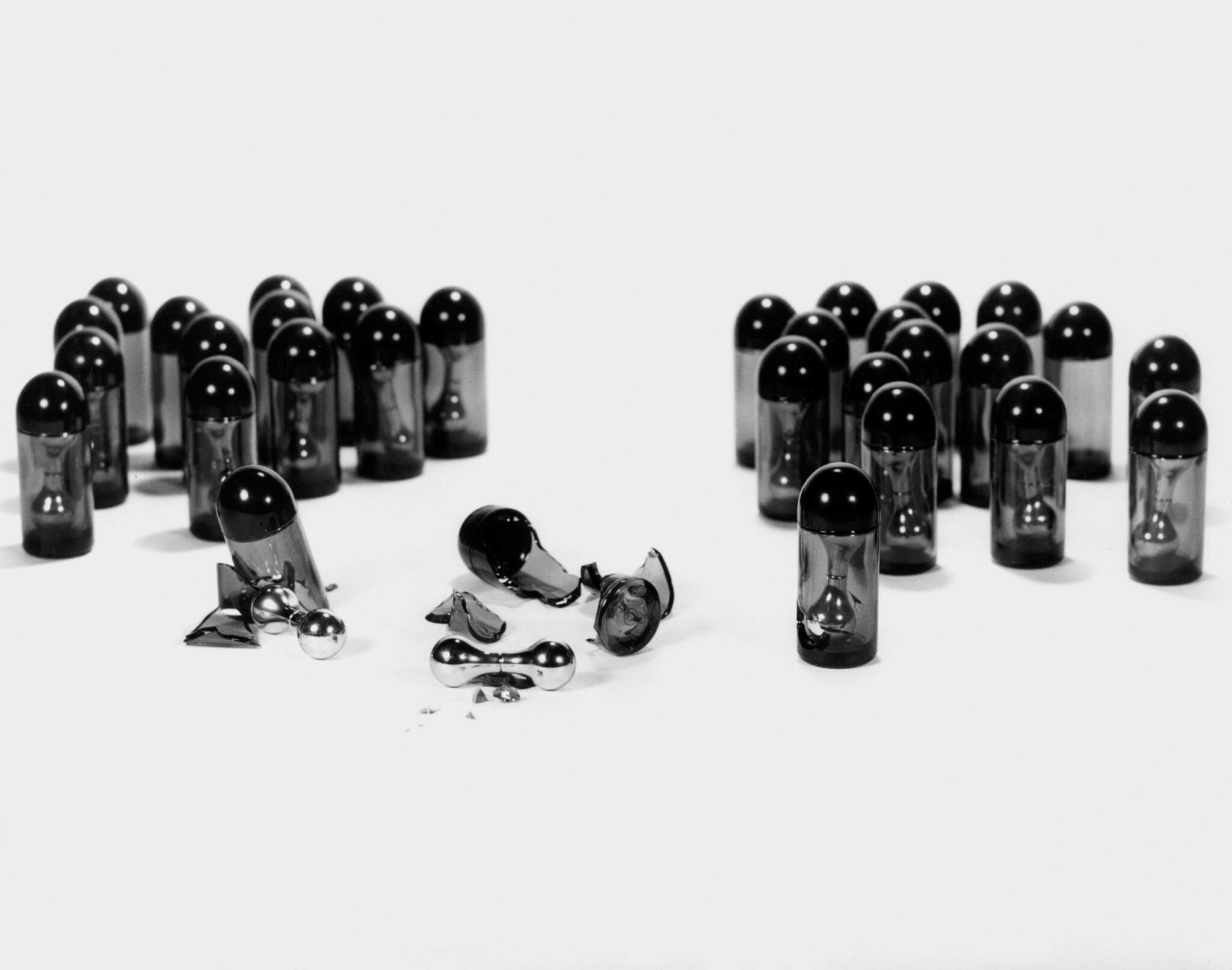

Beal explained an early desire to buy a Kiik, a hyper-placebo stainless steel pill designed by Dallegret. It arrives packaged and prescription-like, although one isn’t supposed to ingest it. The packaging states:

Kiik is a unique, functional product to help cure body discomforts and mind obsessions… This hand pill is recommended for breaking all habits “bad or good” … Use it to stop smoking or start drinking

Beal posted a photo of his eventual Kiik find on Instagram, which prompted co-organizer Kara Hamilton to note that she knew Dallegret, as he was friendly with her father. She explained at the exhibit’s opening that “he was the kind of enigma that would show up around Christmas time.” His madcap example “gave me permission to make art.” This communication also launched the exhibit.

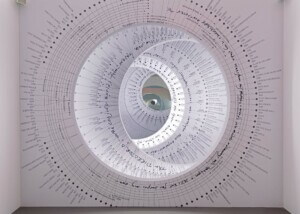

Forms, more than functions, animate Dallegret’s work. The barbell form of the Kiik repeats eleswhere; posters, even an unrealized collaboration to design a playground with Walter Netsch of SOM. As Beal wrote in the exhibition catalog: “An idea becomes first one thing, then another, then yet another—the circle of production is not a closed loop but a spiral that churns out variations and multiple forms in a variety of media until that original idea becomes yet another familiar character in Dallegret’s universe.”

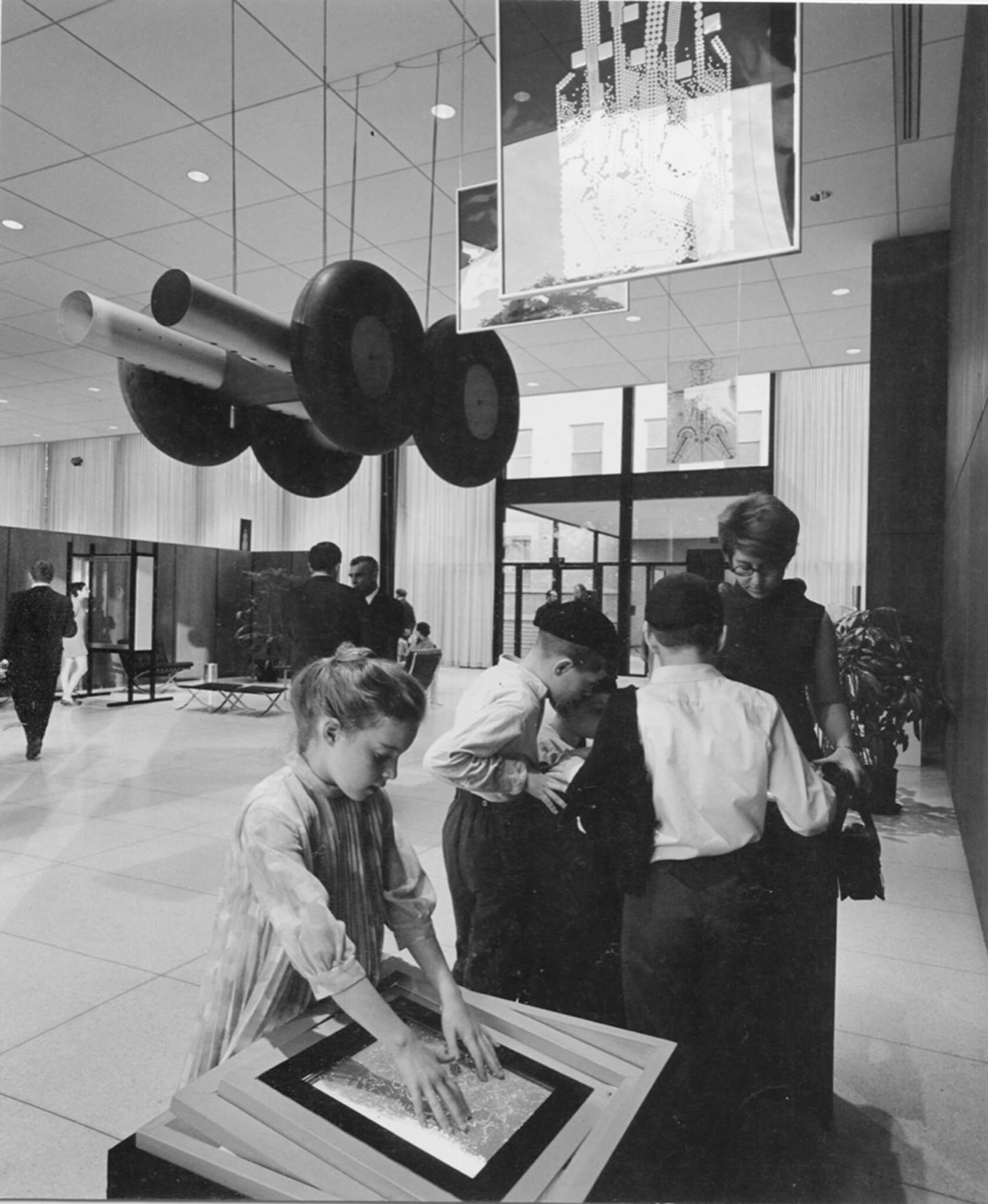

The show stages numerous drawings and photographs of Le Drug, among the most-hyphenated of groovy 1960s businesses (and therefore the coolest), a pharmacy-cafe-disco in Montreal which lasted for two years. In addition to designing the interior, Dallegret also did the branding, designing a variety of logos and promotional materials. Beal explained, “Le Drug was the thing that was closest to incorporating all of these different dimensions of what he does because it was actually a physical built space but there was also a layer of graphic design and product design.”

Dallegret designed other retail interiors for the World Trade Center in New York and Crown Center in Kansas City; both are on view in photographs and plans in New Haven. One unrealized scheme for another fun palace in Montreal, the Palais Metro, appears in its original presentation suitcase—integrated marketing if there ever was any. Nothing happened, but it was a financially viable idea, unlike those pitched by many of his countercultural peers. There is a level of wit present to almost all of Dallegret’s work—“Be a part of the merchandising revolution,” Dallegret’s emphatic example advised, and in a way that’s true.

During remarks at the exhibit’s opening, Dallegret was asked if he particularly regretted any unrealized projects. “I don’t think I can say I have unrealized projects. I have a lot of unrealized projects, but for me they are projects in any case because they are drawn, they are rendered, they are specified, even if they don’t go ahead. They are my projects so I’m happy the way it is.” As an example, a prototype for an anodized aluminum chair prototype appears, but Beal observed that “with that chair, the final product is probably the photographs of him sitting on that chair rather than the piece of furniture that was never produced.”

Dallegret retains a clear attachment to the evanescent; he has made all sorts of event posters and has kept thousands of photographs. Beal continued, “The performance of this event can be just as important as the drawing or the published version in a magazine. That is very contemporary. It’s amazing to think that this work is more than 50 years old.”

Dallegret is also highly resistant to explaining exactly what he was up to. Interviews and his appearance in New Haven will occasionally clarify what he wasn’t thinking—the rest is up to you.

For Beal, it’s notable that the exhibit is at Yale, as Dallegret possesses an architectural background. He could draft beautifully and design structures and furniture but chose to usually do otherwise. The show is interesting in part because “you can clearly see that this mind is a product of a traditional Beaux Arts education, but he took it and pushed it in all these other weird applications,” Beal offered. “François is an amazing model of everything you can do with an architecture education that’s not architecture. If you go to architecture school, you can do all sorts of things; you don’t have to go work for Bob Stern.”

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn.