Architect: David Hotson Architect

Location: Carrollton, Texas

Completion Date: April 2022

An impressive new complex for the St. Sarkis Armenian Orthodox Church in Carrollton, Texas, opened last year. The facility was designed by David Hotson Architect, a practice based in New York.

The church’s site, in a suburb north of Dallas, spans 5 acres. In addition to the church itself, the campus includes an athletic building, a community center, a courtyard, and an event hall (with seating for up to 400 people), all designed by Hotson’s office, working with Terzyan in the role of project architect.

The church’s design was inspired by Saint Hripsime, an Armenian church completed in 618. David Hotson told AN that the church’s inspiration included many designs characteristic of Armenian ecclesiastical architecture, including a monolithic character and sculptural feel.

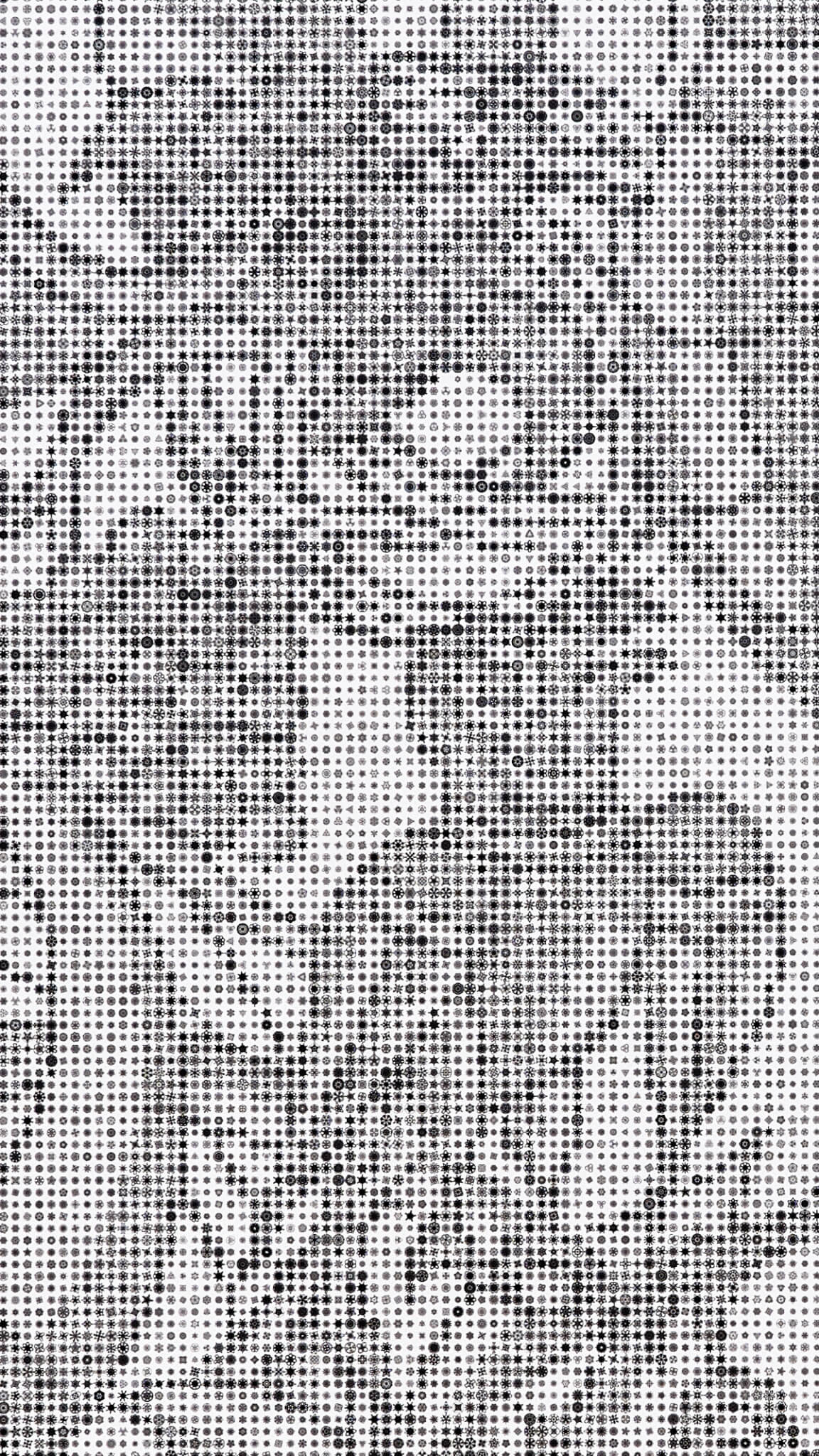

The cornerstone for the church was laid in 2018. Reinterpreting Saint Hripsime’s structural masonry and diagonal piers with contemporary materials, Hotson sought to achieve the modern look Akilian had requested while remaining respectful to the history of the church. Inside, the worship area is a bright, minimal space defined by vaults, domes, and the play of light and sound. Outside, Hotson also skillfully handled the design of a memorial that took shape on the facade: A cross made of 1.5 million pixels, one for each victim of the Armenian genocide, defines the facade’s primary ornament.

Hotson had met representatives from the Italian porcelain manufacturer Fiandre, who had developed a system in which designs could be printed on facade slabs. The ventilated rainscreen system, developed by Fiandre’s sister company, Granitech, could support a “very high resolution” image on a thin slab, Hotson said. The design team incorporated “geometrical and botanical strands” into an Armenian cross to develop a pattern for the facade and took care to frame its major apertures.

The pixelated cross was generated with a Grasshopper script. The pattern appears to be a cross from a distance, but at close range, ornamental motifs traditional in Armenian decorative arts become visible, creating a “nested” pattern, as Hotson described it. This was achieved by alternating the densities of the pixels that the script produced and then arranging the pixels by density, allowing for both the larger architectural-scaled design and intermediate layers.

Samples of the printed panels, 1 square meter in size, were shipped to the site to ensure that the color and contrast were precise, as this was crucial to honoring the monolithic aspect of the church. Other aspects of the facade, including a zinc roof and precast concrete panels, also had to be color matched to make certain the effect continued across the entirety of the exterior.

Equipped with the desire to see to it that the project was delivered with a high degree of precision, Akilian worked as his own general contractor. Fiandre manufactured the panels with a 1-centimeter gap between each unit—the same width as each pixel—ensuring alignment across the entirety of the west-facing facade. The pixel-level layout of each panel was mapped out by Hotson’s office and shared with Fiandre, which began fabrication in early 2020. Production was paused as factory output was brought to a halt by the pandemic, and manufacturing was completed later that year. A local subsidiary installed the facades, which were shipped without breakage from the factory in Italy and put in place with extremely minimal adjustments required.

The patterned facade is west-facing and as such receives intense sunlight in Texas’s climate. Considering this, the choice of an ultraviolet-resistant material was crucial to the project’s longevity.

At the same time, the design team wanted to create a “luminous, ethereal interior lighting condition … entirely illuminated by natural light during the day,” Hotson told AN. Natural light enters the interior through glazing in the dome, in addition to limited glazing on the patterned facade, creating a “present luminous environment” in which color-temperature shifts and cloud coverage are perceivable in the interior.

Hotson said that this move complements the acoustics of the interior, which are shaped to support up to 250 worshippers. The air-conditioning units were located east of the church, and conditioned air was brought into the church at a low velocity through registers under the pews, “eliminating any mechanical vibration … with reverberant vibration acoustics very close to those of traditional Armenian churches,” Hotson shared. This limited energy use, with conditioned air being directed only into occupied volumes of the church. While this approach was aesthetically complementary to the daylighting, it was also designed in respect to Armenian church services, which are conducted as a conversation chanted between the priest, located on the altar, and the choir, located in a loft. The church requires no artificial acoustics and is left acoustically uninterrupted by MEP systems.

As the church’s capacity did not require sprinklers, the vaults were designed as “scaleless, billowing volumes of illuminated space without any contemporary details that would distract from the simplicity of the composition,” Hotson said. The design team worked with Formglas, a Canadian manufacturer, to realize the glass fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC) vaults, which were shaped with double-curved glass. The vaults were shipped and assembled as a kit of parts and set in precast concrete, with their mix carefully color-matched to the gray porcelain and precast facade elements.

Hotson said that a neutral gray “can be the most difficult color to match, as any shift in hue, value, or surface texture can show up.” When projected across large material spans, this can be further accentuated. The GFRC and precast elements could not use the same mix owing to differences in their manufacturing processes, so a methodical process of color-matching samples had to be completed to ensure uniformity in the facade. Exterior pavers and soffit finishes in the church’s entry courtyard were also realized with porcelain, aligning with the joints in the church’s precast walls.

Hotson’s overall design, combined with the advances in printed facades, created a remarkable project, recognized with an honorable mention in the Religious category in AN’s Best of Design Awards last year. The church represents a respectful interpretation of ecclesiastical architecture that advances the use of contemporary materials and fabrication methods. It does not seek to incorporate a memorial element in an additive way but retains it as integral to a complex design. St. Sarkis has already established itself as a home for the local Armenian community and is poised to continue to do so for years to come.

A prior version of this article misstated how Hotson received this commission. It was not won via competition but instead came through Armenian architect Stepan Terzyan, one of Hotson’s former collaborators, who also served as project architect for the church complex.

Project Specifications

- Architect: David Hotson Architect

- Location: Carrollton, Texas

- Completion Date: April 2022

-

Client: Elie Akilian

- Porcelain Tiles: Fiandre

- GFRC: Formglas

- Facade Installation: GV Facades

- Contractor: HighCoCo

- Structural Engineer: GWC Engineering

- MEP/FP Engineer: Gupta & Associates

- Lighting Designer: Tirschwell & Co.

- Landscape Architect: Garden Transformations