In 1983, a 12-year-old named Morris (Marty) Hylton III was captivated by the sleek modernist architecture of fellow Kentuckian Paul Rudolph in Sarasota, Florida, during a momentous birthday trip. Exactly 40 years later to the day, on March 11, as Architecture Sarasota’s recently appointed president and with an unparalleled expertise in matters of coastal resilience and historic preservation, Hylton presented the inaugural Philip Hanson Hiss Award to architect Toshiko Mori, honoring her climate-conscious, resourceful, and site-responsive uses of materials and technology. Not only does her decades of work leading Toshiko Mori Architect further the principles established by the innovative architecture developed in Sarasota during the post-war period, but she also built a number of homes there, responding to and learning from what her predecessors had done before.

The award is named after Hiss, the “impresario” of the Sarasota School of Architecture, a regional modernist movement that flourished from the early 1940s through the mid-1960s. The late Michael Sorkin described him as a “biker and free spirit, bourgeois Medici, citizen-patron, enthusiast, who insisted on architecture.” Hiss arrived in the Gulf Coast in 1948 after establishing a residential development career in New Canaan, Connecticut. He speculated on a barrier island off the coast of Sarasota where he then developed Lido Shores, a modern residential community, with the help of local architects and builders. One of the most outstanding of Hiss’s spec houses was his own residence, the Umbrella House, for which he commissioned Paul Rudolph in 1953. “Rudolph didn’t use the word ‘sustainable,’” Hylton said, “but I would consider these buildings as such, at least at the time, before air conditioning, their carbon footprints would have been really low.”

A mix of locally sourced and prefabricated materials made these experimental houses possible, though unlikely to survive if not for historic designations and restoration efforts. The “umbrella” at the Hiss residence was originally a pergola made up of reused tomato stakes which was eventually destroyed and replaced, yet the original jalousies, straight out of the Sears Roebuck & Co. catalogue, survive. The operational windows are a great example of what made these houses so attractive, as they would keep cool simply by cross ventilation and light modulation.

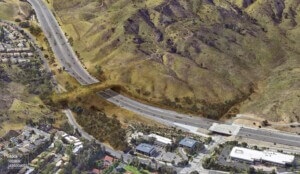

Rudolph collaborated extensively with Ralph Twitchell, the “father” of the Sarasota School. One of their last projects together was a residence built in 1957 on a 535-foot-wide sandbar about 45 minutes south of Sarasota called Casey Key. The house sits between two protected habitats—sea turtles to the west and manatees to the east—in addition to the native island bird habitat of protected wild sea oats and mangroves. It was built almost entirely from Ocala limestone concrete block with a breezeway of screens and clerestory windows. The current owners, Betsy and Ed Cohen, commissioned Mori to design two extensions to the house as independent apartments for their children. The first addition, completed in 1999, stands 17 feet off the ground—9 feet above the habitable height required after Hurricane Andrew—a distance which provides protection from storm surges, and sits shaded by the oak tree canopies, which offer privacy. Steel louvers, fritted glass and concrete blocks modulate the light and protect from solar glare and heat gain, and polished concrete floors mirror the terrazzo in the original house.

The second addition, affectionately named the “mother-in-law” house, was completed in 2002. The modularity and proportions of the steel, glass, and concrete structure complement the original house beautifully, but it is the fiberglass outdoor staircase that steals the show. “You learn as you go, and we learned there is no such thing as rust-proof metal [when] you are between two salt bodies of water and the sun is very hot—it’s just not possible,” said Betsy referring to the first building’s connecting stairs. At Mori’s request, a fiberglass staircase and the rods from which it hangs were built in Rhode Island by Erich Goetz, who custom builds sailing boats for the America’s Cup. “It only weighs 300 lbs; two people can carry it!” Mori told AN during a visit to the home. Twenty years later, it is thriving.

The Burkhardt-Cohen house, as it is originally known, was built to last only 25 years according to Rudolph himself. “These guys came here [building] experimental houses in wood, it’s delicate, they could have been destroyed years ago,” said Mori, “but I think somehow they knew.” Siting is critical for Mori’s process, and while Florida holds strict energy codes and environmental protection ordinances, she still believes a value change is the first thing that needs to happen to avoid disaster.

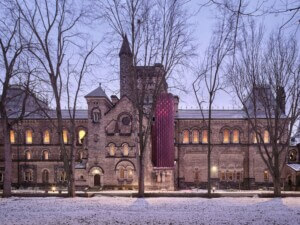

These mid-20th-century structures may have had an expiration date, and without constant, costly maintenance they would be unlikely to survive but, looking forward, there is much to learn from these forerunners. Architecture Sarasota is partnering with top-tier research and design institutions—including Yale, Syracuse, Kean University’s Michael Graves College, University of Florida, University of South Florida, and University of Miami—in order to “prepare model strategies for addressing issues that include coastal resilience, sustainable development, and attainable housing,” Hylton said.

During his lifetime, Philip Hiss promoted the progressive ideas of like-minded individuals and fostered not only architectural but cultural and educational programs as well. He was chairman of the Sarasota County School Board, commissioned nine public schools between 1954 and 1960, and helped launch the New College of Florida. In a 1967 article published in Architectural Forum titled “What ever happened to Sarasota?” Hiss expressed his discontent over later developments uninterested in architectural innovation. Today, after the overhaul of New College’s board of trustees in a spur of rash conservative decisions, one has to wonder: What is happening to Sarasota?

“We have to be public speakers and intellectuals,” Mori remarked about the role of the architect in political and cultural matters. “[We have to] engage with different sectors in the world [to align with] in terms of issues of climate change, quality of life, equity, justice—we constantly have another role to play, to speak up and engage with sectors other than architecture.”

Natalia Torija Nieto is a New York City–based architecture and design writer focused on mid-20th century modern and contemporary design and architecture.