In late November 1806, while in Colorado on an expedition to map the length of the Arkansas River, U.S. Army lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike wrote in his journal, “The Grand Peak now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day’s march to have arrived at its base…. I believe no human being could have ascended to its pinical [sic].”

The Grand Peak to which Pike referred was, nonetheless, later named for him. (To the Ute it is known as Tavá kaavi, or Sun Mountain.) The irony of Pike’s pronouncement is that today Pikes Peak in Colorado is one of the most visited mountains in the United States, accessible by foot, car, or cog railway. Attracting half a million visitors each year, the peak has become known as “America’s mountain.”

By the mid-2010s, the popularity of Pikes Peak had taken its toll on the existing summit visitor center, a low-slung building with a plastic sign that wouldn’t have been out of place in a Colorado Springs strip mall. “Everything was all mushed together. The line for the restrooms would snake through the gift shop. It was hot, crowded. It was really not a very good experience,” Alan Reed, the president and design principal of GWWO Architects, told AN. More problematic—and costly— was the fact that the existing visitor center had been built on top of the permafrost. “Literally from day one, that building began to settle,” Reed adds. “It was an annual ritual to go in and shore the building back up and level it out.”

In 2015, GWWO Architects, working with Colorado Springs–based RTA Architects, was hired to design a new summit visitor center. Opened in a partially finished state in June 2021 to avoid an interruption in visitor services, the building had the final touches put on this past September.

The new $65 million structure better organizes the visitor experience and provides a wide variety of activities and spaces from which to enjoy the mountain’s panoramic views, including new overlooks, dining terraces, and an exhibition gallery. GWWO’s “build your adventure” strategy stems in part from the need to manage the large “pulses” of visitors who arrive at regular intervals on the cog railway. The goal, Reed said, was this: “If there’s 300 people in the building, it feels comfortable. If there’s four people in the building, it feels comfortable.”

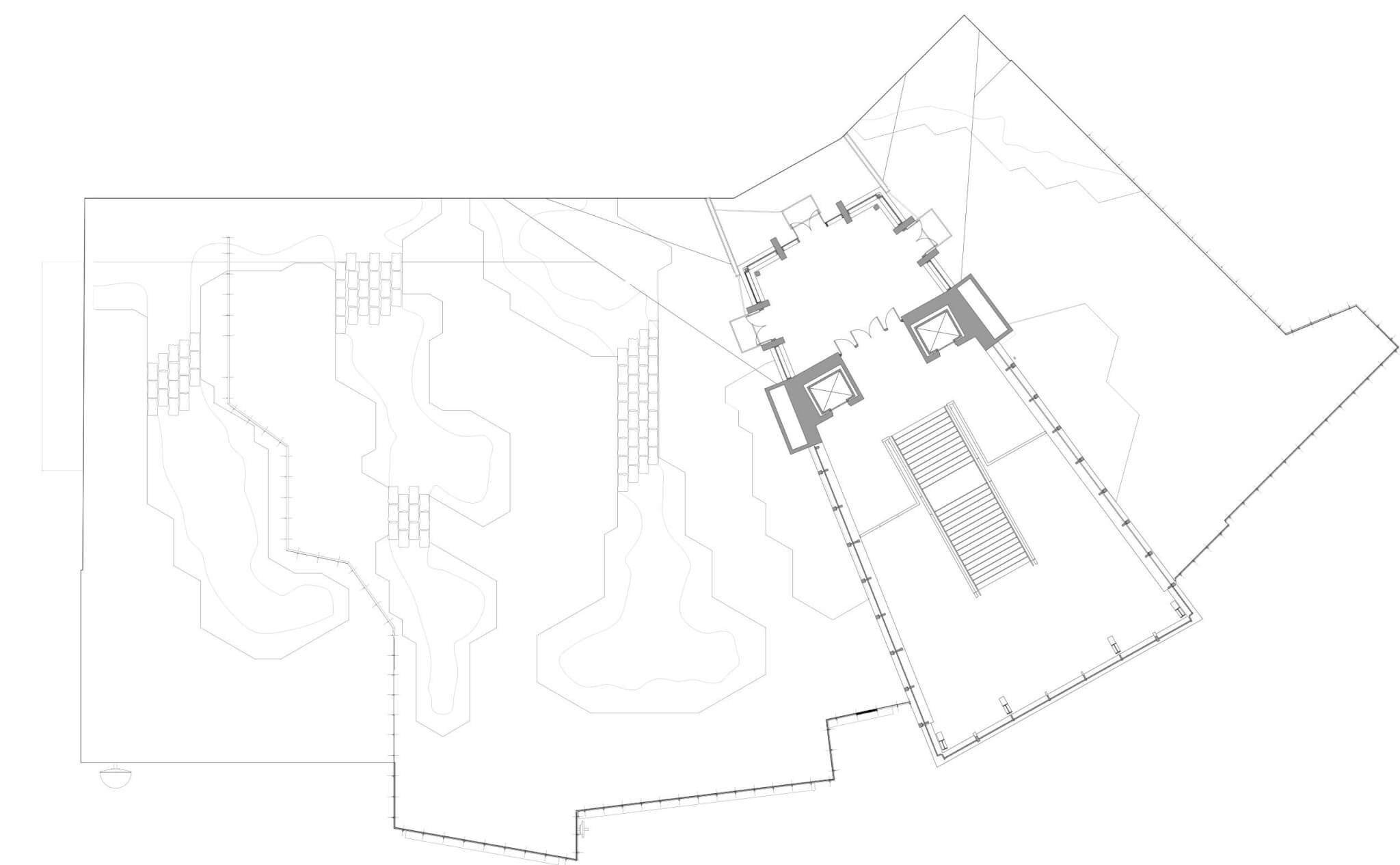

Architecturally, the visitor center takes its cues from its harsh yet breathtaking environment. Tucked into the southeast shoulder of the mountain, the 38,203-square-foot visitor center appears from the parking lot to be little more than a pavilion. Upon entry, the full height of the space materializes, with a prominent staircase that tumbles down the natural slope of the mountain to reveal a main lobby whose 30-foot- tall glazed facade frames views of Mount Rosa (a peak Pike did manage to ascend). Materials such as locally quarried quartzite sandstone evoke the stark beauty of the mountain, while a new boardwalk system helps ensure the regeneration of the heavily degraded tundra ecosystem.

Designed to meet the standards of the Living Building Challenge in an environment where temperatures can reach minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit and winds up to 230 miles per hour, the structure features a super-high-performance building envelope—its precast concrete walls have an R-value of 60 and its roof an R-value of 120—and is powered almost completely by an off-site solar array. Previously, all potable water was trucked up the mountain, and all waste trucked down—requiring almost-daily trips. In the new visitor center, new technologies, such as vacuum flush toilets and Colorado’s first blackwater–to–gray water treatment system, reduce the frequency of those trips by half.

Siting the building on the south side of the peak wasn’t an obvious choice, according to Reed. Three of the architects’ four original schemes located the new visitor center on the opposite side. “The northwest side has the most dramatic views, and of course we were drawn to that,” Reed explained. But over the course of multiple meetings with stakeholder groups and the public, some of which were attended by several hundred people, the design team heard that community members wanted that vista unsullied. “They really wanted to maintain that northwest view out on-site so that you’re really in the elements,” Reed said.

Given the site’s remoteness and mercurial conditions, GWWO and RTA wanted as much of the building to be pre-fabricated as possible. Only the stone that clads the building’s precast concrete walls was installed on-site; the rest of the structure was trucked up in large, preassembled modules. Still, it took three and a half years to build the visitor center, in large part owing to weather delays.

To avoid the structural issues that plagued the last visitor center, the new building sits directly on bedrock; the excavated permafrost was reused on-site to create boulder fields and to provide the subbase for the newly paved road and parking lot. It may sound counterintuitive to add impermeable surfaces on a project committed to minimizing its environmental impact, but in this case, asphalt was more ecologically attuned than the alternative. In 1998, the Sierra Club sued the City of Colorado Springs and the U.S. Forest Service to force them to pave the road that winds its way up the mountain, primarily because of the impact that loose gravel was having on local water resources. “The gravel was choking streams down the mountain,” Reed said. (The road was finally paved in 2011.)

The large quantities of exposed small rocks and gravel on the summit also presented a serious problem for the architects. Picked up by 200-mile-per-hour winds, the material could quickly become a very real threat to the expanses of glass that were critical to the visitor center’s design. Early on, the design team conducted material tests at the summit, and the gravel “destroyed the glass,” Reed remembered. The team explored several solutions to the gravel problem, including an exterior net that would protect the glass, but ultimately added a deployable shutter system on three sides of the building.

“If the wind’s out of the east, say, they can drop those shutters, and it protects the glass from snow, gravel, anything [that] wants to blow, but they can leave the other sides open,” Reed explained, adding that the southern facade was left exposed because its orientation protects it from the prevailing winds and limits its exposure to gravel and other material.

Wrapped in glass and stone, the new Pikes Peak Summit Visitor Center adopts a posture of deference and inclusivity that befits America’s mountain. The building is meant to be experienced both as an outgrowth of the mountain itself and as a viewfinder, with the architecture dissolving before visitors’ eyes until ultimately they feel that there is nothing between them and the horizon.

Timothy A. Schuler is an award-winning journalist and magazine writer whose work focuses on the built and natural environments.