Architect: BNIM

Location: Iowa City, Iowa

Completion Date: January 2022

Nearly 15 years after a flood heavily damaged the original Stanley Museum of Art on the University of Iowa campus, a new museum building designed by BNIM opened in January 2022. The University’s renowned collections of African and 20th-century art have returned to the campus, including Jackson Pollack’s Mural painting, which was quickly evacuated during the flood and has spent the last 14 years traveling to art institutions across the world to appear in temporary exhibitions.

The 86,200-square-foot facility features new gallery spaces, outdoor terraces, and a sculpture garden. The museum also houses public space for research, a viewing room to study artwork up close, and a storage room. Located near Gibson Square Park, the College of Education, and College of Engineering, the museum contributes to the overall university campus adjacent to the Iowa River in Iowa City.

One of the primary design prerogatives for the new museum was flood prevention. The first level of the new facility, as well as all mechanical systems, are situated both above grade and above the 500-year flood level. In the event of another flood, the building is capable of maintaining the temperature and humidity necessary for the conservation of its collection for at least 72 hours.

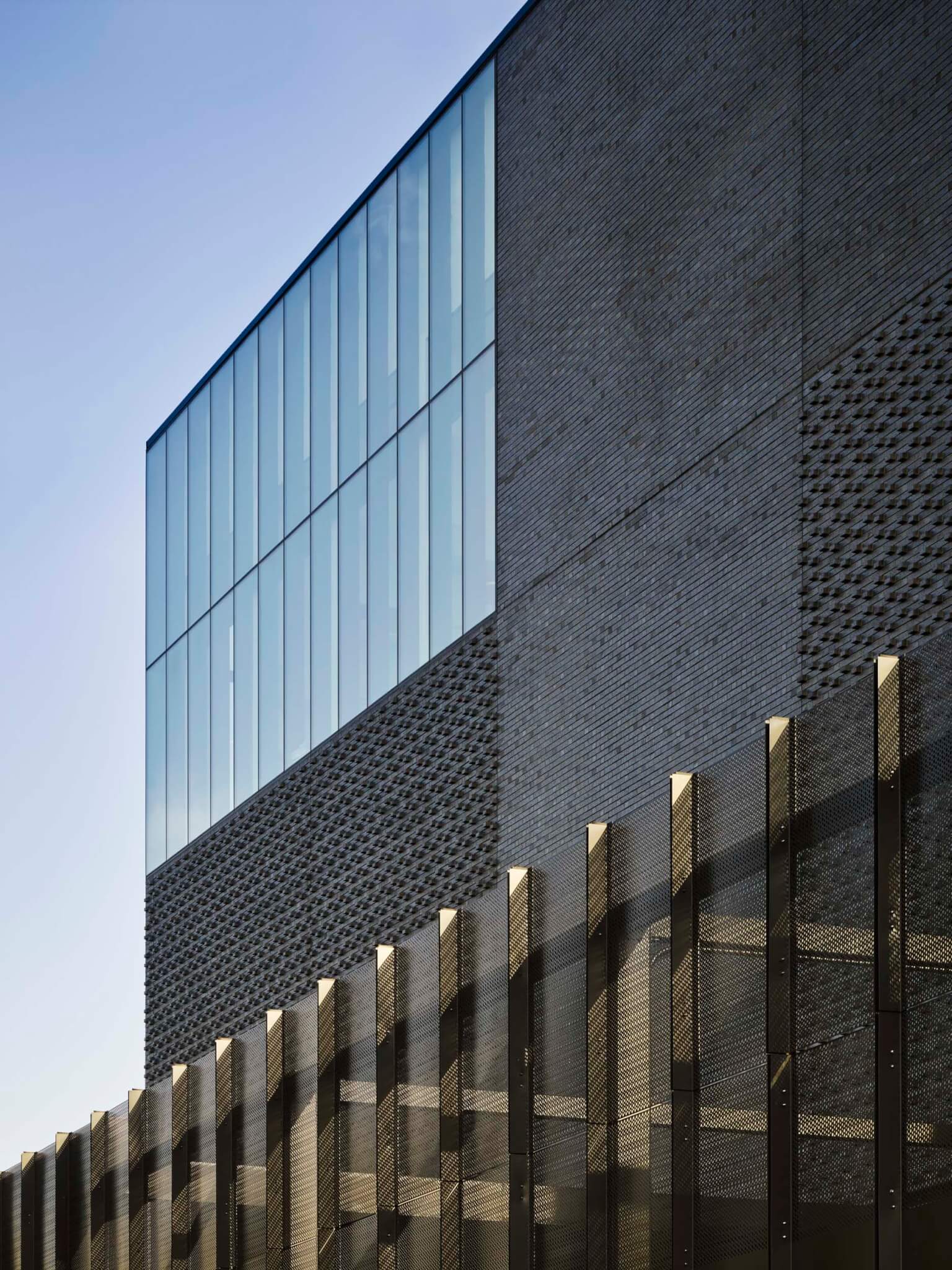

The facade, which is clad in dark brick, complements and distinguishes itself from the lighter brick masonry of the buildings surrounding it. This dark color was achieved through a manganese wash that gave the brick a reflective sheen able to refract the sky and take advantage of daily and seasonal changes in light conditions.

BNIM principal Carey Nagle told AN, “The multiple vantage points that reveal a variety of sub-patterns in the brick coursing and texture required the installation teams to plan alignments in the horizontal, vertical and double diagonal directions to ensure the intended aesthetic and pattern was revealed in the finished product, ultimately requiring a very high level of tolerance and craft.”

The firm added that textured-cast-in-place concrete, as well as linear stone masonry, were also considered for the facade. Similarly, the design team considered cast-in-place-concrete and concrete masonry unites for the back-up wall assembly, but ultimately settled on cold-formed metal framing. The masonry was locally extracted and manufactured, and offers a reduction in embodied carbon when compared to other considered cladding assemblies.

In a Tally analysis, the brick cladding and cold-formed metal framing of the back-up wall contributed to an overall 47 percent reduction in the total global warming potential (GWP).

The facility’s glazing was largely pre-determined by conservation considerations, leading to a virtually windowless gallery space to protect the museum’s collection. This lack of sunlight was compensated by expansive windows for the museum’s public spaces and additional areas which do not display the collection. High-performance triple element low-e glazing assemblies with ultraviolet filtration were selected for spaces adjacent to conservation areas to maintain the desired temperature and humidity conditions.

Alongside the glazing choices, daylighting strategies resulted in 36 percent light density savings. Likewise, the installation of a high-performance building envelope achieved significant carbon reductions, primarily through high R-value insulation, mass, and detailing components which maintain consistent thermal, air, and vapor barriers across primary systems.

The museum’s main floor and lobby is encased in a glass facade that fills the space with sunlight, and functions as a street-facing display to showcase selected artwork and the public programming. Between exhibition spaces, the workers installed natural light-filled voids.

BNIM worked closely with Eckersley O’Callaghan (EOC), the project’s envelope consultant. EOC performed THERM analysis of various facade conditions, and helped to improve the buildings energy performance, heat transfer and condensation conditions, constructability, water management, and long-term durability. Meyer Borgman Johnson, the project’s structural engineer, helped achieve performance goals through the delivery of a thermally broken brick ledge detail.

“The nature of the facade texture and coursing, along with its very intentionally composed intersections with glazed systems, required a high level of precision and coordination amongst the masonry and glazing contractors,” Nagle added.

Project Specifications

- Architects: BNIM

- Location: Iowa City, Iowa

- Completion Date: January 2022

- Client: University of Iowa

- General Contractor: Russell Construction

- Museum Consultant: Walt Crimm

- Civil Engineer: Shive-Hattery

- Structural Engineer: Meyer Borgman Johnson

- Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing: Design Engineers

- Envelope Consultant: Eckersley O’Callaghan

- Envelope Commissioning: Resource Building Envelope Specialists

- Masonry: Endicott Clay Products

- Masonry Subcontractor: Seedorff Masonry

- Curtain Wall: Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope

- Moisture Barrier: Grace Construction Products

- Glazing: Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope

- Exterior Lighting: Lumenpulse