Mass Support

City College of New York – Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture

141 Convent Avenue

New York

March 21–May 8

A uniquely American mania has taken hold in the area of housing reform. For the last few years, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and regional newspapers across the U.S., along with architects, planners, and real estate experts, have proffered the misguided idea that reformation or elimination of zoning would allow the free market to somehow produce an adequate supply of affordably priced dwellings. According to the going logic, if regulations were eased, real estate developers and homebuilders would flood the market with inexpensive units that they would sell at below market rates for mysterious reasons and then donate their potential profits for the benefit of society. Advocates also mistakenly believe that bankers would willfully loan money for this cause at subprime interest rates and, presumably, excuse developers who sell units at less than their offering plan.

Zoning-reform activists may not have been paying attention in 2008 during the subprime mortgage–backed securities crisis. The federal government opted to shore up the banks and allow them to take away the homes of hundreds of thousands of families rather than sacrifice the difference between their declining market value and mortgages. The same thing happened recently, when three banks collapsed in the second-largest incident in American history. The ideology of regulators is to protect bankers, who have no interest in giving away potential profits. No one is giving a break to buyers unless forced to do so. Given this trajectory, the idea that zoning reform by itself, without other regulatory mandates, will have more than a marginal effect on the price of housing is madness. The free market will not save us.

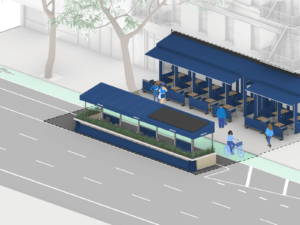

What are other solutions for the perennial question of housing? The exhibition Mass Support, which was on view at City College’s Spitzer School of Architecture, injects a world of other possibilities into this impoverished imagination of market-based housing policymaking. Based on the work of Stichting Architecten Research (“Foundation for Architectural Research,” or SAR), a think tank active in the Netherlands between 1964 and 1990, the exhibition is curated by Curatorial Research Collective (CRC) and designed by Office ca. (Cassim Shepard, a member of CRC, brought the show to Spitzer, where he teaches; Galo Canizares, one half of Office ca, is also a member of CRC.) The installation stages its arguments on custom walls in a gallery whose floors are marked out in tape with lines representing the SAR’s ideal flexible dimensions, surrounded by ten contemporary projects that reflect the principles of the SAR on the gallery’s stationary walls.

In presenting the framework for a new way of thinking about mass housing, the exhibition pivots on two assumptions about how we can improve the quality, supply, and affordability of dwellings.

The core premise of the SAR, led by Dutch architect and theorist John Habraken, was that greater flexibility and customization by users in the design of multifamily buildings could enable mass housing to solve common problems experienced in socialist housing blocs, which had been widely constructed in Europe and the U.S. before and after World War II. Family sizes and structures inevitably change over time. In the SAR’s models, walls can be rearranged, apartments combined and divided, and even plumbing fixtures moved to allow for alternate floor plans without the need for owners to move or live in inadequate quarters each time their lifestyle changed. Different groups of users and types of communities may also want to share common spaces, experiment with cooperative living arrangements, and assimilate sociological and cultural differences. The architect should be an enabler who mediates between these needs and the builder. “The occupant can only play his part when he is trusted with a number of decisions concerning the layout and the equipment of his dwelling,” an early description of the foundation’s principles argued.

Habraken sought to be as neutral as possible about the form and style of architecture he used as examples. He was reluctant to publish drawings that might appear prescriptive, a point that resonated with architectural theorist Christopher Alexander in a letter displayed in the exhibition in which he expressed allegiance with Habraken’s approach. “[A]t long last something had been said that means a breakthrough from the heritage of CIAM into the real problems of the living city,” Alexander wrote. “There are only too few of us who really understand that form is the result of an immensely complicated process and that those who declare themselves responsible for our material environmental should be prepared to start thinking about that process in a creative way.”

A multifamily structure might require various kinds of supportive services: social workers for youth aging out of foster care and group homes, mental health services for the formerly unhoused, and health aids for seniors in need of care. These may require another parti altogether. All of these variations could be plugged into the fixed grid of a “mass support” structure. SAR’s early thinking analyzed what constitutes the mass support structure as distinct from the private domain of individual users and astutely observed how even the shared support structures can vary depending on a society’s expectations of what should remain a common resource versus what belongs to the private sphere, and how much freedom an individual has a right to exercise.

The second aspect of the SAR’s argument stressed in Mass Support concerns the need to nourish integral collaborations between architects, clients, and the home-building industry. To succeed, the program anticipated working closely with house manufacturers rather than proliferating an antagonistic relationship with the existing industry. The program required customizable parts that users could alter without extensive skills, and for that they needed cooperation with producers.

While the SAR did not succeed in building a large number of housing developments in Holland or other parts of Europe, Shepard, founding editor of Urban Omnibus as well as a filmmaker and City College lecturer, worked with collaborators at The Architectural League of New York and CRC at Eindhoven University of Technology, where the SAR was based, to highlight a number of developments that resulted from the research, as well as a selection of contemporary projects that echo its themes.

Prefabrication and individual autonomy represent one tranche of take-aways from the group’s work, ideas exemplified by the Stanton Court bungalows in Sheepshead Bay by Gans & Company, built to aid in recovery from Hurricane Sandy, and the Plugin Houses by People’s Architecture Office, an ADU kit that can be inserted into unusual urban sites. Cooperative living and community control are another: The design of La Borda housing cooperative by Lacol in Barcelona follows input from its self-organized owners and includes communal as well as commercial spaces. R50 cohousing in Berlin by ifau and Jesko Fezer + Heide & von Beckerath, a 20-unit apartment house for affordable and collective living, includes a flexible floor plan and community space for neighborhood use. The San Riemo housing cooperative in Munich by Summacumfemmer and Juliane Greb advocates social solidarity in its provision of services such as a women’s therapy clinic and support for disadvantaged youth.

Another worthwhile trajectory returns to zoning reform. Groups like the University of Michigan–based spatial justice advocates Cadaster; Neighbors for More Neighbors in Minneapolis; and University of Toronto professors Richard Sommer, Michael Piper, and Simon Rabyniuk analyze and advocate for updating—or even abolishing—outmoded regulations to achieve greater density in communities, especially in suburbs in Canada and the U.S., where it is often noted that single-family uses historically served to exclude Black residents after segregation became illegal. Zoning reform figured equally importantly in the exhibition’s corresponding Mass Support symposium, held on April 26, and was the central theme of the talk given by Emily Badger, a reporter for The New York Times, for the school’s annual Mumford Lecture. Research demonstrates the importance of zoning reform as one key aspect of housing policy that can encourage greater affordability in certain types of communities by allowing things like smaller lot sizes, less stringent parking requirements, and multifamily developments where they are excluded.

Mass Support premiered at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands last summer, and there are plans for the show to travel to other schools in the future. For its New York audience, the show is a valuable exploration of a potent subject. It uplifts historical research that will be news to many U.S. scholars and shares instructive contemporary models which the exhibition will continually update in future shows with new examples.

The show doesn’t fully address the missing link that is essential for successful implementation of housing models that are flexible, designed for resident agency, reflect community desires, increase density, and work closely with home-building industry: government intervention. In Europe and the U.S. after World War II, countries substantially increased the housing supply and its affordability through price-control mandates, massive direct funding for multifamily buildings, low-interest loans for buyers backed by federal insurance, and tax breaks (which now overwhelmingly inflate housing prices). It worked and produced a middle class. It could work again tomorrow. Without this precondition, it’s highly likely that architectural ambitions for housing will fail to produce anything except expensive condos.

Stephen Zacks is a journalist and project organizer based in New York City.

A prior version of this article misattributed curatorial credit for Mass Support. It was curated by the Curatorial Research Collective; Cassim Shepard is a member of that group.