What’s half a billion dollars to a city as rich as New York? The refurbishment of Lincoln Center’s Geffen Hall? Just over half a billion dollars. The price tag for the Perelman Center at the World Trade Center? Another half a bil. The budget for the new modern and contemporary art wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? The same, for now. And, opening this week, Studio Gang’s addition to the American Museum of Natural History, known as the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation? Just under a half a billion dollars.

Five hundred million dollars seems to be the price du jour. But is New York getting enough bang for the bucks? In the case of the Gilder Center, which has transformed a fusty and sometimes off-putting museum into a welcoming and relatable institution, the answer is resounding yes.

Michael Kimmelman, the architecture critic of The New York Times, began the chorus of hallelujahs with a review published online the night before most writers got inside the building. (It’s standard procedure to give the Times first look, and doing so certainly paid off for the museum and Studio Gang.) Kimmelman wrote that he was breathing a sigh of relief. Eight years ago, when the design was first made public, he worried that its naturalistic forms, suggesting cliffs, canyons, and caves “might end up looking overcooked.” And he was right to worry. The 230,000-square-foot building, which completes the western side of the museum, along Columbus Avenue, was to include an atrium composed of shotcrete, liquid concrete sprayed through nozzles onto rebar, creating, essentially, fake rock. The stuff one expects to see in a natural history museum, but only in dioramas, now is the natural history museum.

The building’s exterior was also designed to be swoopy and naturalistic, though sheathed in Milford Pink granite rather than in shotcrete. There are other museums with similar facades, including Douglas Cardinal’s National Museum of the American Indian, in Washington, D.C., and his Canadian National Museum of Civilization in Ottawa. But those are freestanding buildings, which gives them room to dance to their own drummer. Gang’s version, by contrast, would be squeezed into a complex of right-angled buildings. In that context, it risked being read as an overly literal translation of the phrase “natural history” or as an effort to appeal to the museum’s school-age constituency with a Disney-like attraction. Would the Matterhorn be next?

As it turns out, it is precisely the naturalistic forms that make the Gilder Center work. That’s because a key goal was to solve the museum’s circulation problems. Many of its hallway-like galleries, with the dinosaur skeletons and giant geodes, were dead ends, making the museum feel unfinished, unnavigable, and, frankly, uninspiring. (Dead ends are a terrible metaphor for a museum of exploration.) To do away with the dead ends, Gang’s building had to plug into them. That required an agile, asymmetric floorplan; shotcrete’s flexibility helped the walls bend wherever they needed to bend. As it turns out, the humble material, as applied, looks quite elegant, while making the room feel like a destination for spelunkers.

“The architecture enhances the feeling of discovery,” said Gang, the proud daughter of an engineer father and a librarian mother. Her inner engineer reveled in the building’s form (developed initially by taking blowtorches to blocks of ice in the courtyard of her office in Chicago), while her inner librarian thrilled to its function: “It’s really about science education, which is near and dear,” Gang told me of the facility, which includes 18 classrooms. “It will help people discover science, at a time when science is under attack.”

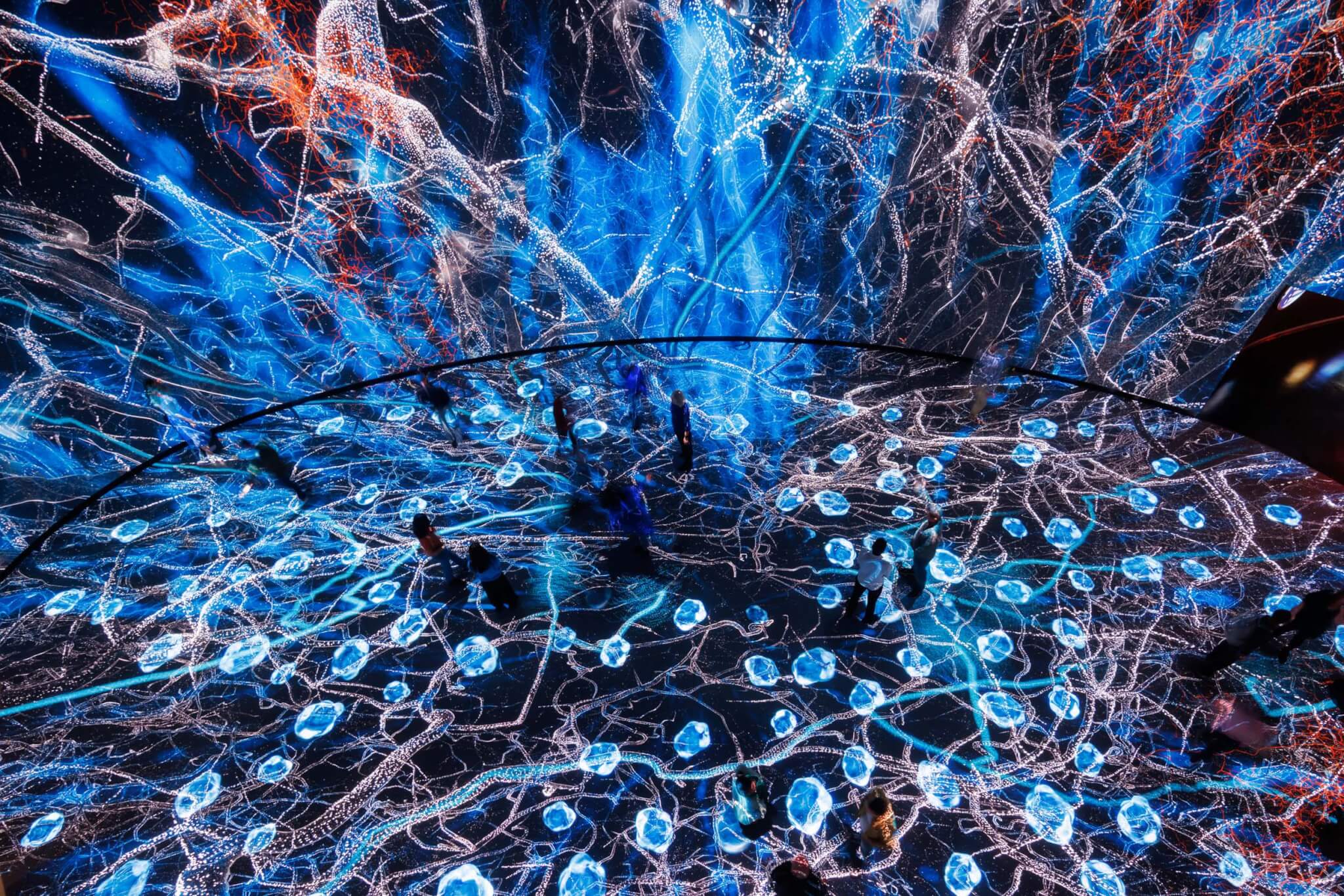

Indeed, the Gilder Center is much more than an entry pavilion. Among its attractions is a large oval room designed for Invisible Worlds, a 12-minute immersive video installation that responds to the movements of its audience. Another winner is the butterfly conservatory, where thousands of specimens live beautifully but briefly. There’s a large insectarium, one of many areas in which exhibition designer Ralph Appelbaum excelled. The displays incorporate tiny actual insects, large sculptural insects, and huge photographic depictions of insects. They all work together nicely: A museum for kids doesn’t require formal rigor or consistency of scale. The only disappointment is a glass and metal habitat containing thousands of leafcutter ants. The ants seemed lethargic during last week’s well-attended press preview. Perhaps they were confused by the right angles that, ironically, appear in their habitat but almost nowhere else in the new building. I bet the ants would like a shot at the shotcrete!

There are other amenities, including a handsome new cafeteria with a hive-derived honeycomb ceiling, and a spectacular library centered on a concrete column that splays out overhead like a mushroom. Throughout the atrium are glass vitrines, dubbed “visible storage,” containing a range of objects from the museum’s vast hoards.

At the press preview, Gang called the project “a ten-year labor of love.” Of course, she had plenty of other projects during those years, and she has emerged from the decade as perhaps the most formally inventive architect working today. Her breakthrough project—Chicago’s Aqua tower (2009)—was less environmentally friendly than its supporters claimed, but its facades were striking enough to attract attention. Aqua couldn’t be more different from Gang’s Writers Theatre (2016) in Glencoe, Illinois, an all-wood building as carefully constructed as a Nakashima table. The theater looks nothing like her Solar Carve (2019), a black-glass building in Manhattan’s Meatpacking district that steps back from the sun. And Solar Carve couldn’t be less like her Populus, a hotel in Denver modeled on the bark of a birch tree (expected to open in 2024). Like Aqua, Populus isn’t as sustainable as its developers—who dubbed it “climate positive”—would like us to believe.

To its credit, the museum isn’t claiming the Gilder Center contains the solution to global warming. (Wouldn’t that be nice?) Its green features include windows that admit large amounts of light; an air conditioning system that keeps cool air near the floor; and all the shotcrete. Although manufacturing cement can be carbon-intensive, the use of shotcrete eliminates the need for formwork (which is likely to end up in landfills) and offers a finished surface without the need to layer on additional materials. All of that is good for the environment.

What would really make the building green is longevity—the greenest building is one that doesn’t need to be replaced—but there’s no evidence the Gilder Center is more durable than the typical 21st century building. (In fact, as Justin Davidson noted in New York Magazine, you can chip its shotcrete surfaces with a fingernail; Christopher Hawthorne, who reviewed the project for The New Yorker, even took a bit of it home as a souvenir.) What is true is that the building’s naturalistic forms make it appear environmentally sensitive. Is making a building look like it’s “at one with the earth” a way of getting credit where credit isn’t really due?

It’s also true that the theme of many of the exhibits, taken individually and collectively, is that everything in nature is connected. An important lesson! But it would have been nice if the building addressed the challenges of the Anthropocene more directly. I can imagine a screen displaying the museum’s real-time energy consumption, divided into categories (how much for lighting, how much for cooling, how much for displays, etc.). And I can imagine another screen indicating where that energy is coming from (how much nuclear, how much natural gas and how much hydroelectric, the big three sources in New York). Once you know how much energy the museum is using and where it’s coming from, it’s easy to compute the amount of CO2 being emitted as a result. That could be on the next screen. Then there’s the energy used to make the building in the first place, its so-called embodied energy. An estimate of the building’s embodied energy, expressed in terms of tons of carbon emitted, and an explanation of how the number was arrived at would be helpful. A final display would track, in real time, the museum’s efforts (if any) to offset both its embodied and operational carbon emissions. It’s hard to think of a better use for a tiny bit of Studio Gang’s Center for Science, Education, and Innovation.

Fred A. Bernstein is the winner of the 2023 award given by the American Academy of Arts and Letters to an American who explores ideas in architecture through any medium.