Portals: The Visionary Architecture of Paul Goesch

The Clark Art Institute

225 South Street

Williamstown, Massachusetts 01267

Through June 11

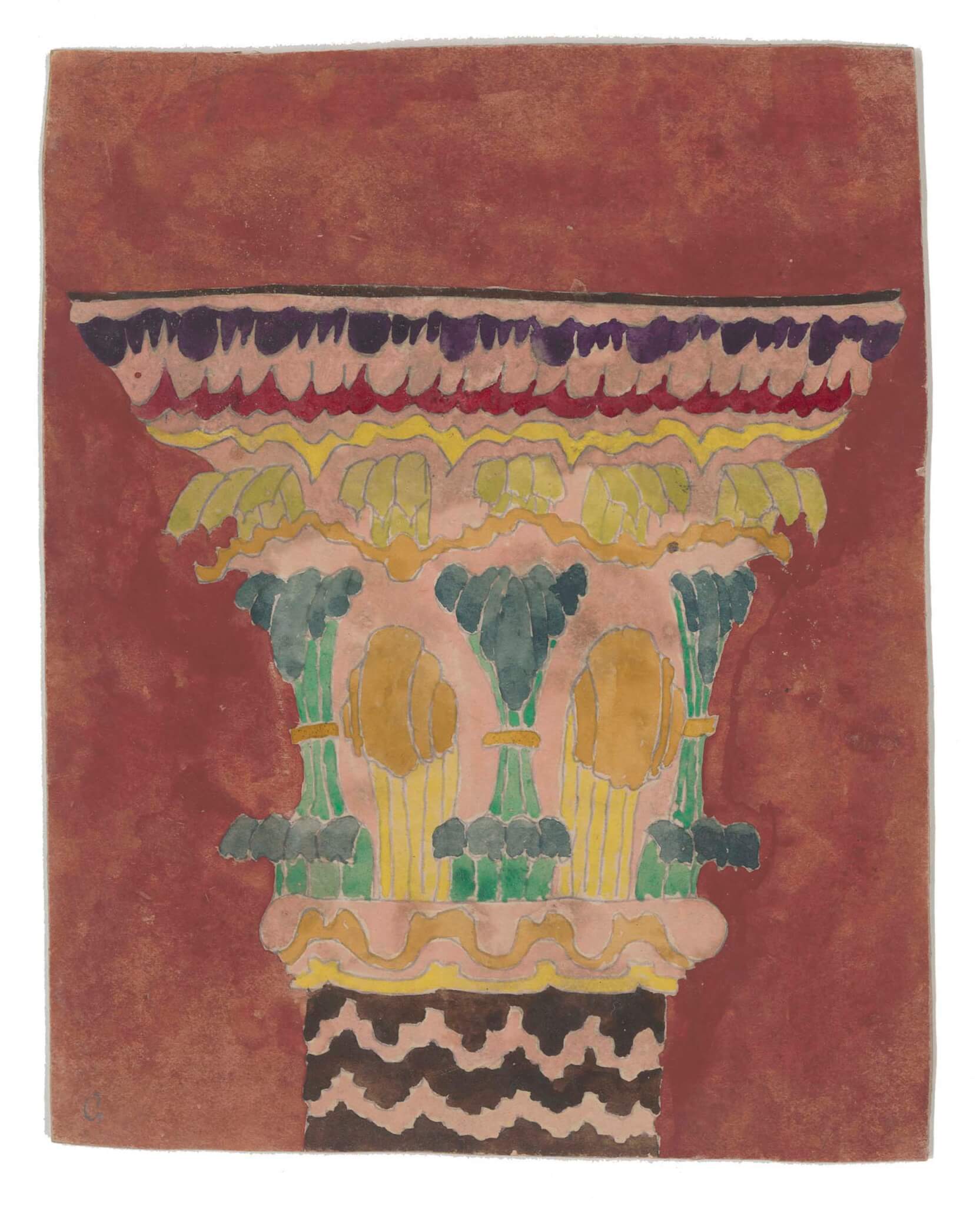

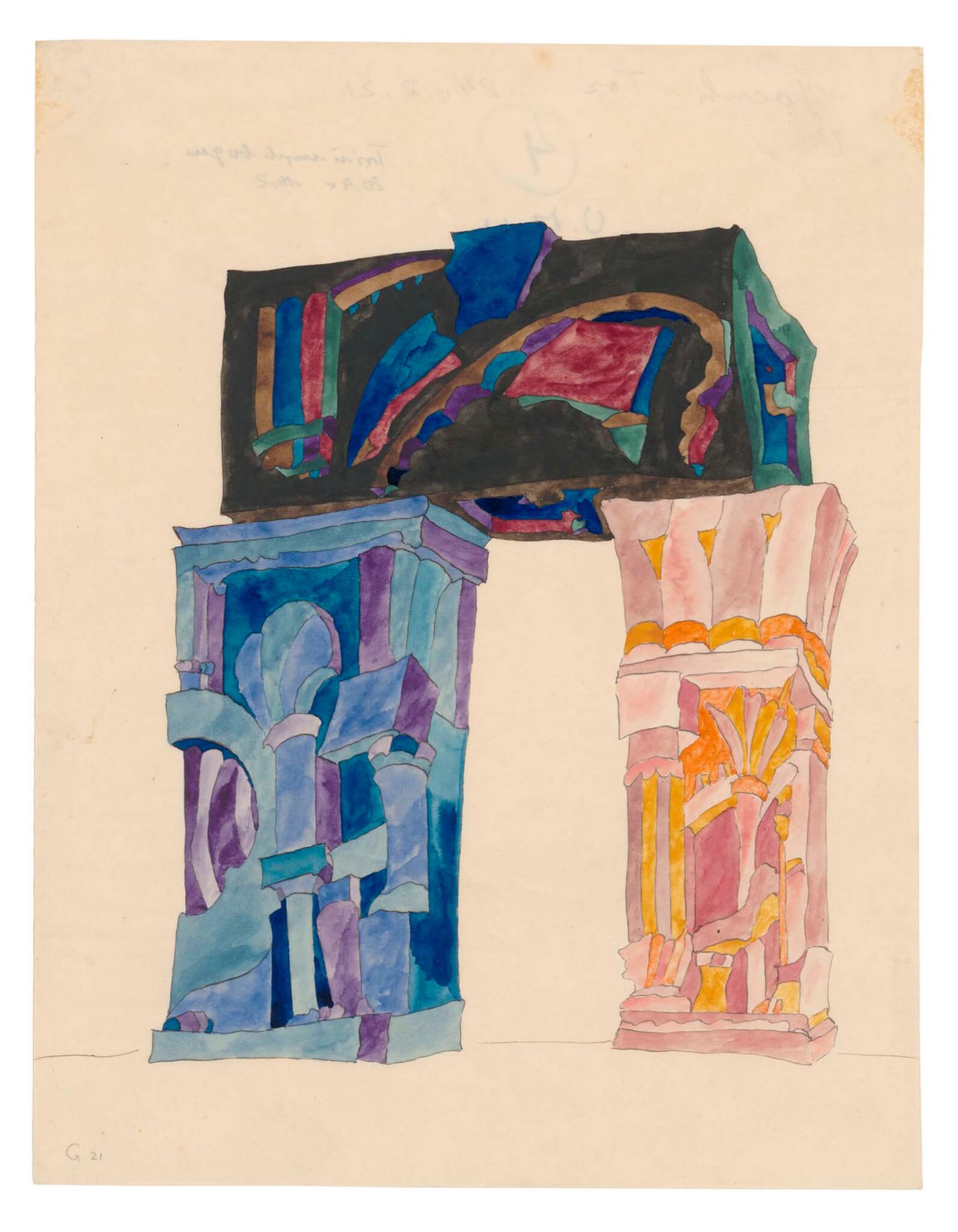

A gouache and ink drawing of three arches in soothing colors was the frontispiece for an architectural manifesto issued in Berlin in 1921 that called for building a new future atop a defeated empire. It’s an odd image. The portals could be page borders of a medieval illuminated manuscript, or a floral arrangement, or designs (albeit shaky) on the walls of a mosque.

The drawing is by the early 20th century architect Paul Goesch, whose eclectic imagination contributed to the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Work Council for Art), designers of bold visionary projects that went unbuilt. Those architects—Bruno Taut, Hermann Finsterlin, Hans Scharoun and others—sent designs to each other in a correspondence they called the Glass Chain or the Crystal Chain (Gläserner Kette). Goesch’s beguiling structures were unusual in that club of fantastic architecture, as it was also called, but he was part of it. Few beyond his circle knew of him until half a century later.

Goesch’s work was inspired by the colors of Matisse and the Fauves in France, his hardheaded peers who later formed the Bauhaus, and by objects from outside of Europe that filled German museums in the late 19th century.

Portals: The Visionary Architecture of Paul Goesch at the Clark Art Institute is the first exhibition devoted to Paul Goesch outside Germany. A Lutheran converted to Catholicism who leaned toward the Anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner, Goesch never built a building and barely practiced. He suffered from schizophrenia, which put him in institutions for much of his life. His fate worsened under Hitler. Nazi psychiatrists who diagnosed Goesch as incurable had him killed in 1940 when they found him “unworthy of life.”

The 34 works by Goesch at the Clark, all on loan from the Canadian Centre for Architecture, will be a discovery for those who see the show. (More than 2,000 drawings by Goesch survive.) The lush colors suit the show’s title—the drawings can feel like seductive portals to another realm, as Goesch reaches back into history to quote from traditions and motifs from around the world. The thickly applied color gives the designs the spatial feel of three dimensions.

A few years younger than Taut and Finsterlin, Goesch did not build a future on paper with towers reaching into the sky. Nor did he create biomorphic shapes, like Finsterlin’s unruly waves announcing a new era. Goesch’s drawings, harmonious and mostly gentle, signaled that, if a new built environment was going to rise, as his Gläserner Kette crowd hoped, this architect would not be the one demolishing structures to make way for it.

After World War I, with much of Europe in ruins, Goesch was drawing buildings that sat with serenity, lined not by walls but often by columns, sometimes Orientalist in feeling, that rose into towering flower blossoms evoking ancient Egypt. It’s hard not to think of Louis Kahn’s radiant palette in his drawings of ancient sites from 1950.

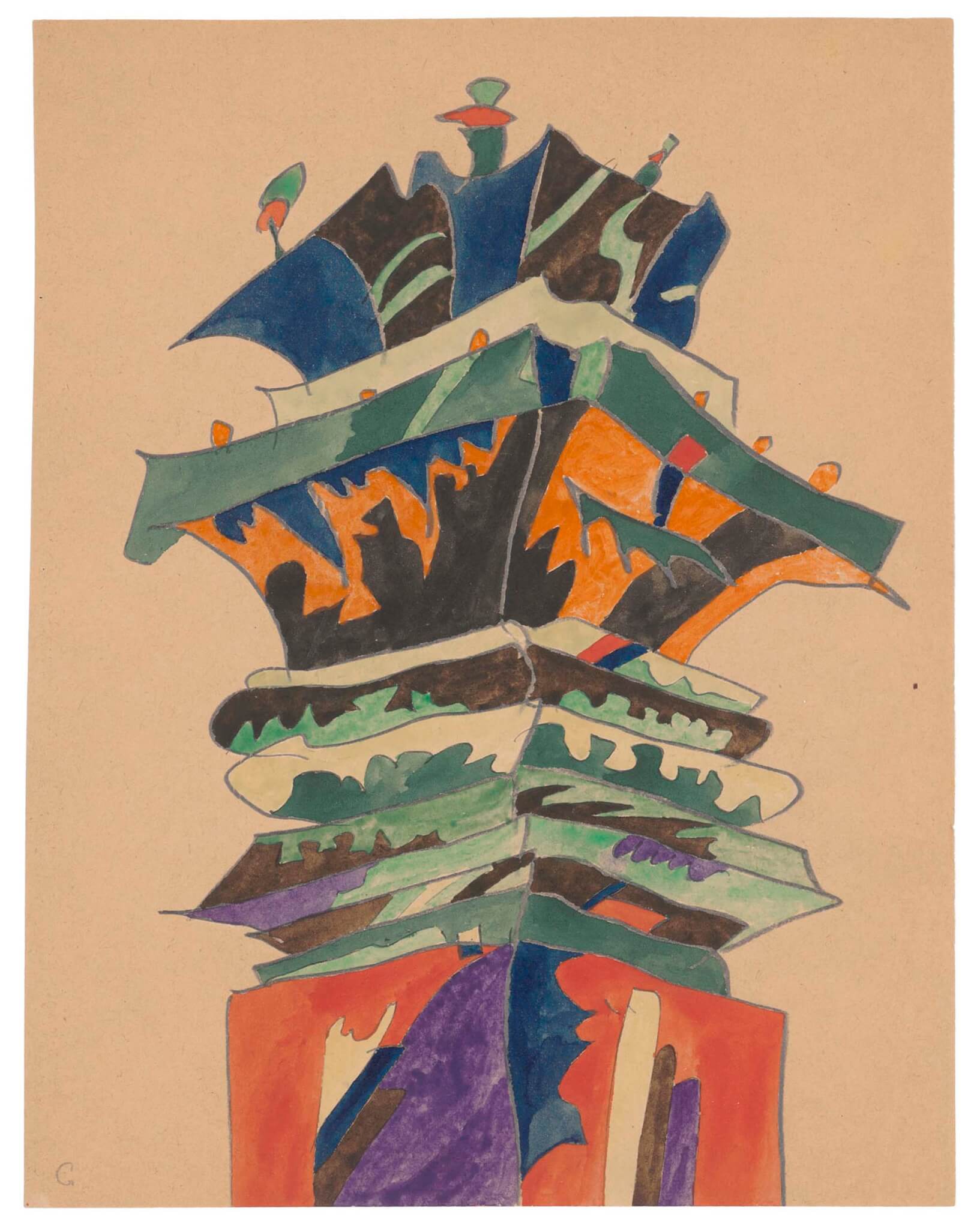

In other buildings that Goesch imagined in color and monochrome, a baroque obsession to cover any and all space on a surface appears to be at work, whether in temple-like structures with sculptural busts on every exterior wall, as in India or Cambodia, or with marks and scrawls of some secret waiting to be decoded. Historians of art by the mentally ill—what was then called “patient art” or “pathological art”— might see that overloaded urgency as compulsive.

Yet most of the images on view feel softly improvised and constantly eclectic. The Clark show’s curator, Robert Wiesenberger, notes in the informative catalog that “while most of his peers rejected historical styles, Goesch gathered up global forms like so much spolia, recombining them in a pastiche that might be considered neo-historicist or even proto-postmodern, for its playfulness and pluralism.”

Wit was another element, sometimes at the expense of his peers who aimed to wring adornment out of architecture. In one drawing, two upright blocks, one of hues in blue, another in pink, bear the weight of a larger horizontal block atop them in green. Is Goesch showing us first principles of architecture— how a building stands up—or mocking the folly of oversimplifying designs that won’t be built anyway?

As Goesch made images while a patient, museums like the Kunsthalle Mannheim collected his work. So did the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg, which pioneered studying “pathological art.” (The institution was wary that Goesch’s work, which emerged from his training as an architect, wasn’t “pathological” enough.) In his essay for the catalog, critic Raphael Koenig noted that Goesch “was successively deemed too ‘savant’ to belong to the emerging canon of the ‘art of the insane,’ and too ‘naïve’ to be labeled an avant-garde artist.”

That hairsplitting didn’t deter Goesch’s Nazi overseers. Several of his works expunged from the collection of the Kunsthalle Mannheim resurfaced in a 1938 traveling “Degenerate Art” show in Berlin and Leipzig. On a Nazi propaganda poster that circulated widely, “Cleanup of the Temple of Art,” one drawing was stigmatized with works by other mental patients as “cultural Bolshevism.” Goesch, for the Hitler regime, was an enemy on two counts, as a schizophrenic and as a member of the dreaded avant garde.

It took decades after World War II for psychiatrists and museum curators in Germany to overcome problems in classifying Goesch. Portals at the Clark introduces us to a rare imagination from a moment of ferment in architecture, before the artist was murdered, another victim of Nazi horror.

David D’Arcy, a journalist and critic, is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper.