In May, Pratt Institute School of Architecture established a memorial fund in Bill's honor. A beloved educator and mentor, Bill taught at Pratt for nearly three decades and was a fixture of the school and its New York network (his walking tours of the city were renowned). He also directed summer studios to Berlin and Milan, cities he knew equally well. Whether in the classroom or out on the sidewalk, in the Lower East Side or Mitte, Bill inspired his students to travel, observe, and interrogate the places around them.

Your generosity will enable talented, deserving students of architecture and urbanism to travel, observe, and interrogate—just as Bill would have wanted. Help us continue his legacy by contributing to the fund. Visit giving.pratt.edu, and under the "Designation" option, please select the William "Bill" Menking Memorial Fund. We thank you for your support!

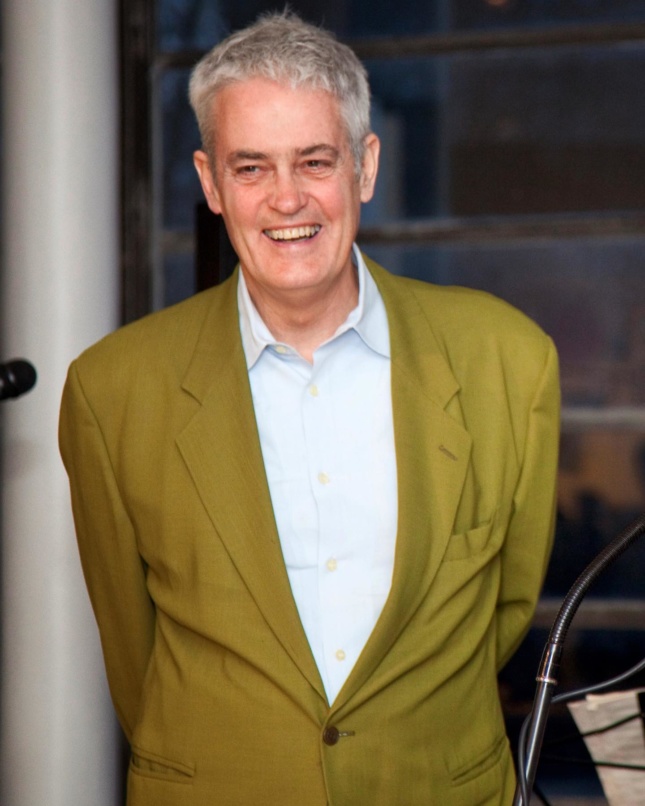

William “Bill” Menking, architectural historian and educator who was cofounder and editor-in-chief of The Architect’s Newspaper, passed away on Saturday at his Tribeca, Manhattan, loft after a long battle with cancer. He was 72 and is survived by his wife Diana Darling and their daughter Halle.

Menking was an invaluable part of the architecture community of New York as well as nationally and internationally. Best known for founding The Architect’s Newspaper with Diana Darling in 2003, he was also a prolific curator and writer. Menking was on the Board of Directors at the Storefront for Art and Architecture and The Architecture Lobby, as well as a tenured professor and trustee at Pratt Institute. He was the curator of the 2008 U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture and organized many exhibitions, including The Vienna Model: Housing for the Twenty-First Century City and Superstudio: Life Without Objects, the latter of which became an important book on the Italian collective. He was also the author of Four Conversations on the Architecture of Discourse (2012) and Architecture on Display: On The History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture (2010); both were co-edited with Aaron Levy and published by Architectural Association in London.

For Bill, the discourse and production of architecture were as much about people as they were ideas. In fact, the two were interchangeable in many ways. Likewise, art was his life and he made life into an art. It is sad that someone who enjoyed life as much as Bill would ever have theirs cut short, but we can take solace in the fact that Bill did more living in his 72 years than most of us would do in three times that long.

His friends were his colleagues, who he loved to connect and gather, whether for a gallery talk or for a round of beers. “I am sorry for those who didn’t experience his amazing [1998] Archigram show at the Thread Waxing Space [in New York], just one of many mega projects in his determination to share his boundless enthusiasms with us,” said Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History at Columbia University. “The same generosity spread into the weekends when he staged Texas-style BBQs in his garage in Greenport, on his beloved North Fork.”

This zest for life and love for travel took him around the world, most of all to Italy; he literally attended every Venice Architecture Biennale since it started in 1980. He was something of a one-man tourism bureau for the places he visited, always excited to give the best recommendations for architecture, museums, sightseeing, or restaurants. He would rarely lead you astray; usually one wound up far off the beaten path. “Bill was such a luminous and restless intellect, drunk with the delight of connecting the loose ends of architecture, urbanism, and art,” said architect Marion Weiss. “His enthusiasm for radical architecture, urban exceptions, and great food was infectious.”

Bill had a knack for being in the center of the action. Perhaps because it was in his DNA—he descended from some of the earliest British settlers in America, as well as the Okies who continued this trailblazing tradition. Bill was born at the Ramey Air Force Base in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico in 1947 and raised in Stockton, a small town in California’s Central Valley, where he worked as an air-traffic controller for crop dusters and once played football against O.J. Simpson. He attended UC Berkeley to study architecture and urban studies from 1967–1972, and I can only imagine the things he saw there (something about Governor Reagan bombing him and his friends or something). Clearly, this immersion in American counterculture helped shape his excellent taste and avant-garde predilections, from radical architecture to social activism, to local clothing shops and DIY oyster shacks.

During school, he headed to Florence, Italy, where he met key players of the radical architecture movement such as Archizoom Associati, Superstudio, and Grupo UFO. His interactions with this community of radical thinkers, designers, and architects would form the foundation of some of his most important research and curatorial practice, including multiple shows on Superstudio as well as a seminal book (written with Peter Lang) published in 2003. It laid the groundwork for his future work on Archigram, the British cousins of the radical Italian architecture movement.

In 1974 and 1975 he worked as an organizer for the United Farm Workers, helping establish labor unions in rural towns in central and southern California, before landing in downtown New York City at a time of heightened cultural production. Hanging among this vibrant art scene, he met Dan Graham, with whom Bill drove around New Jersey documenting suburbia. In typical Bill fashion, he got a job as a server at Studio 54, where he witnessed iconic moments like when Bianca Jagger rode a white horse through the club. He moved into his famous Tribeca loft space on Lispenard Street, which he built out into a classic downtown dream loft that he was always excited to offer up as a venue for fundraisers, or for meetings and holiday dinners with AN staff. He had one of the better-stocked liquor collections, almost entirely gifts from foreign visitors who would stay with him when visiting New York.

With an acumen for learning and navigating the urban environment, Bill began working in the early ’80s to work as a location scout for film and TV in New York. This led him to sunny and decrepit Miami, where he took up an art director post on Miami Vice; his contributions to the show helped rehabilitate many of Miami’s now-celebrated modern and Art Deco buildings. In the ’90s, Menking moved to London to attend the Bartlett School of Architecture. During his time there, he became close with Peter Cook and other members of Archigram, and wrote for architectural publications including The Architects’ Journal and Building Design, both then thriving in England. The experience inspired Bill to import this model to the United States, and The Architect’s Newspaper was born in 2003 in his loft. “We had no idea what we were doing, and it made it better!” he often told me.

“In an age where information is fundamental to our lives, The Architect’s Newspaper filled a gaping void, with straightforward reporting on what’s happening in the profession day to day that we weren’t getting from the two remaining monthly professional journals, and certainly not from newspapers,” recalled Robert A.M. Stern, architect and regular reader of AN. “It also brought to our shores an American version of the lively discourse we’d been reading from the U.K.”

“AN is just what it says it is, a newspaper. Strange that no one used this concept before Menking,” said Phyllis Lambert, founder of the Canadian Centre for Architecture and avid AN reader. “Like The New York Times and the Guardian, it is my source for deeply informed, judicious information about what is happening in the field.”

We will continue to celebrate the life of Bill Menking, who will be remembered as someone who was always in the right place at the right time, agitating and connecting, breathing life into whatever was around him. Bill’s memory will live on not only through the continued influence of The Architect’s Newspaper, Pratt, and Storefront, but also through all the lives he touched with his mentorship and guidance.

Everyone who came through the paper took some part of Bill’s thinking with them. For me, his influence is palpable: How to avoid the status quo or the cliché. How to work in and around institutions. How to do more with less, and not be too precious. How to keep the social mission radical. Many of my fellow travelers came through Bill, including my Rockaways fishing buddy Walter Meyer and my Sunday pasta buddy James Wines, both, like Menking, equally lovers of life and intellectual discussion.

I can’t count the number of people whose work I studied in architecture school that I ended up meeting through Bill in social situations, nor, I suspect, can others. “Bill was someone who gave you everything without asking anything in return. He was a connector of people, ideas and souls,” said Eva Franch I Gilabert, former director of Storefront for Art and Architecture and now director of the Architectural Association. “If I just made a map of all the people he connected me to, I would be able to make a portrait of a generation of idealist, honest, generous, radical and eternally young.”

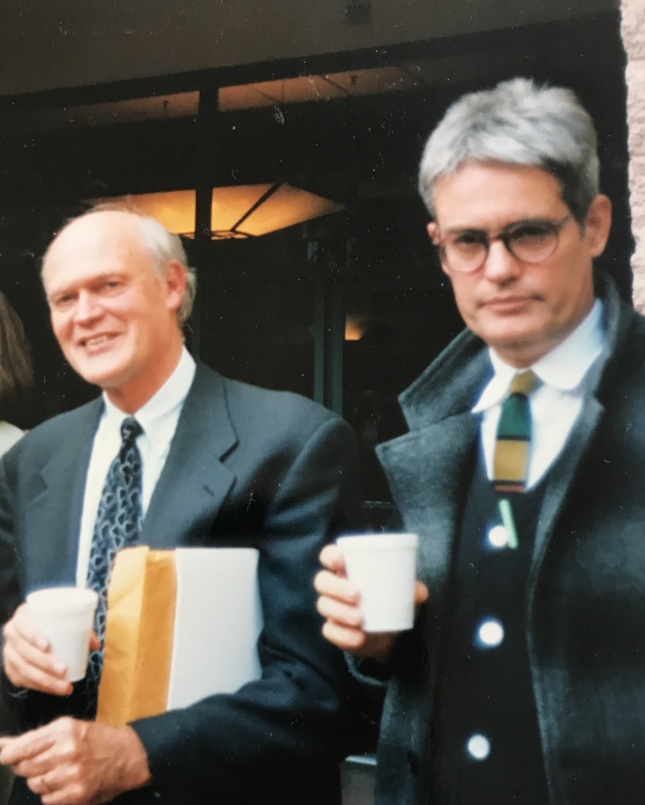

One time, Bill and I were hanging out with his buddy Alastair Gordon outside the tent at Design Miami, when Hans-Ulrich Obrist came up to us. Taking a moment to pause, Hans said it best in his signature accent, with a big, shining smile: “Bill Menking is a legend.” –Matt Shaw, former executive editor, The Architect’s Newspaper

I first bonded with Bill decades ago in my twenties, while editing a zine called Stroll, whose themes were gritty, controversial, and news the mainstream press didn’t touch. Bill shared the publishing bug, as witnessed years later when the idea to launch The Architect’s Newspaper took hold.

In 1988 while digging into an architectural themed issue of Stroll profiling the upcoming exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture, curated by Philip Johnson at The Museum of Modern Art, Bill unearthed one of the more intriguing stories about the genesis of the exhibition. Through a series of investigations and his highly curated network of architects, academics and critics, Bill’s story “Fresh Air From the Windy City” highlighted the work of Chicago architects Paul Florian and Stephen Wierzbowski while also revealing the original premise for the MoMA exhibition. It forecast Bill’s inevitable future career as an architecture news man.

Over the next three decades, Bill became a friend, beach buddy, social connector, party instigator, and constant source of news and inspiration when it came to architecture and design. Weekends on the North Fork were spent conceptualizing menus, gossiping, and preparing meals for a group of mutual friends in the infamous Greenport barn. Along with teaching, and editing, cooking food for a community was a passion he loved to share. Those afternoons were when Bill was at his absolute best, multi-tasking while preparing seafood, cajoling, gardening, simultaneously tending to the needs of Halle, Diana, along with a house full of guests.

One of Bill’s many, many acts of kindness occurred days after Hurricane Sandy hit, when he, Diana, and Halle drove out to Long Island and let me hitch a ride to the North Shore. We drove through practically every borough, from Manhattan to Brooklyn, through Rockaway Queens to pick up AN employees, so the newspaper could continue publishing from their Greenport home. Bill drove, touring the tragic devastation while navigating uprooted trees, fallen branches, downed power lines, and debris that covered the narrow roads and finally safely delivering me at my parents’ house off Long Island Sound.

I could go on about all the coffee meet ups, press events, house tours, art openings, yard sales, beach picnics, and adventures in the city and road trips traversing back and forth to Eastern Long Island, which were frequent, and always memorable. Bill’s big heart, relentless spirit and generosity touched so many lives. La Dolce Vita my friend. Life is just not the same without you.

With everything that’s gone down in the last few months, it’s hard to know. It’s hard to remember where things stand. Where we’ll stand. I know this though. I understood, or better yet, I figured out where to stand because of Bill. That’s a fucking gift that’s rare. And, it’s going to take time.

A Love Letter To Bill… Fragments from our lives…

Bill loved People and People loved Bill!

Many claim “social practice” as part of their working method; Bill embraced this essential form of social engagement decades before it was a buzzword. Philosophically, in his daily life, Bill performed what Kant might refer to as “radical hospitality,” where the “other”—meaning “everyone”—was always welcome at his table… Generosity, conversational warmth, and kinship were the norm…

Bill was social media before social media existed… Decades ago, He would send me postcards, share photos, books, maps, and social contacts from his travels… To further inform my worldly adventures… But better yet, was to travel and derive with Bill. His embrace of the locale, his knowledge of history and current cultural trends made for a more passionate form of psycho-geography… together.

Bill’s sharing of his loft with people from around the world is now legendary… I just wish that we could all be there now… As I know that he would too…

Years later, somehow we are all connected yet paradoxically worlds away; Bill has 5000 Facebook “friends” that he cultivated far and wide. The current outpouring of love and admiration for Bill on the web and here this evening are a testament to his optimistic embrace of technology in the service of all things human.

Bill said yes to every engagement whether he could make it or not… In his mind he could attend them all… Locally, globally or in the cloud… If I’m not mistaken, I think that he may have RSVP’d to being here, together, with us now!

Bill loved the World and the World loved Bill!

In my mind, Bill was a fluid hybrid of personas from the cultures and places that he traveled, loved, lived and worked…

An American folk hero on constant road trips and an advocate for social equity and civic responsibility with a love of architecture and design, American cities, their planning, people, and histories… A tour, a walk or a joy ride with Bill, in NYC or even better yet, the outer boroughs, Long Island, or Jersey was a treasure trove of local lore and secret spots to explore…

A European Bon Vivant—or more specifically, as they say in Italian Grande amante della vita e della sua bellezza which translates best as “lover of life and all its beauty”… Any trip to Europe with Bill was an immersive discovery… He was able to navigate cultural difference with ease… along with an uncanny ability to be casually “in the moment.”

A British scholar, pop star, and eccentric—Bill possessed a wealth of historical, contemporary, and obscure knowledge with a remarkable memory while also knowing the hippest pub or current pop music and, simultaneously, an absent-minded professor, missing appointments, having lost his jacket, keys, tickets, phone, or laptop… All part of his endearing charm…

Culturally, Bill was astute at bringing the periphery into the center and vice versa, looking for the perfect balance between High and Low, Insider and Outsider, always with an egalitarian point of view. Outlier, vernacular, and popular cultures were equally relevant to what was coming from the academy in his curious, active mindset of cultural collage.

Bill loved Women and Women loved Bill

A tall handsome man with a natty dress code and a charming demeanor… Ever notice his socks?… Bill was fortunate to have had extraordinary and supportive woman at his side over the years. His long-term relationships with Dara, Carla, and Diana produced shared qualities and life-defining moments for all of their futures.

Dara and Bill met in Florence, Italy in 1969, where radical experiments in architecture and media art were steaming like a strong espresso. They both seemed to find their callings while in Florence, in different ways, while supporting each other’s passions. In 1975 they moved from the epicenter of progressive idealism and the student movements of Berkeley, California to the formative bohemian culture of downtown NYC and furthered their experimental journeys into art, architecture, and the city. Ultimately, in different ways, and finally, providing mutual success for both of them…

Carla, brought with her a vivid cosmopolitan style, committed civic engagement, and a quick wit when she married Bill in Florence in 1988 after many years together in their loft on Lispenard Street. The fashion designer Emilo Pucci, by absolute chance, happened to be officiating their ceremony and after seeing the bride and groom, gave a sermon on the importance of beauty and style in our daily lives… Bill, of course, invited many of his friends, including Judith and me, to come along on their honeymoon… Much to Carla’s chagrin…

Diana, his loyal anchor and tugboat captain until the very end, married Bill in 1993 and shared his embrace of social causes and, most importantly, made Bill’s dreams of not only having a family but also of starting a publishing enterprise come true. She saw the merits in Bill’s knowledge. social network, and world travels while maintaining the foundations for a successful business together that should endure and honor his legacy well into the future.

Bill loved Dogs and Dogs loved Bill

Might we speculate on a perspective of Bill through the eyes and minds of his dogs over many years?… They were always his loyal friends… Who imprinted onto whom?… Was Bill becoming more canine?… Or were the dogs becoming more like Bill?

Jude, shared with Dara, was a big mellow English sheepdog and loved to go for long walks in the Berkeley hills and especially later in New York City, sniffing out all of the streets and sidewalks, discovering the really fragrant spots together with Bill.

Hugo, shared with Carla, was a happy and very energetic English corgi, obsessive about sports, sprinting across the loft to fetch and retrieve a designer doggy toy from waking until slumber. The only respite was when Cal Berkeley football was on TV, Bill and Hugo on the couch together… Tuned out, yet entirely tuned in to the big game.

Coco, shared with Diana and Halle, was an upbeat and selfdetermined cockapoo, often only motivated by good food… Especially from the barbeque after pulling weeds all day with Bill in the garden of their summer home in Greenport. Time on the beach also did them both a lot of good…

I love Bill

In self-reflection, we shared a regional California bond. Idealistic and intellectually curious West Coast neo-beatniks with an embrace of counter cultures where daily life was celebrated, with just the right amount of hedonism and of course a desire for guacamole and tortilla chips…

Bowls and bowls of pasta and Italian wine together… “Come over, I want to talk to you about an idea,” whether personal or professional. As Bill’s ideas grew in scope and scale I had to increase my consumption of pasta and wine, as we always maintained a gift economy of ways and means… Bill truly was a gift…

To Halle, your father loved you so much and wanted you to have the most beautiful life… Judith and I think the world of you…

To Diana, your strength and foresight in Bill’s final months… Finally bringing him home to a place of love and comfort is truly heroic in the best sense of the word…Thanks to Diana, I got to speak with Bill shortly before he gently slipped into a peaceful siesta. My trying… to find words… express my gratitude and admiration for our friendship and all of the adventures that we shared… came out mostly as… I love you… Thanks, for being my friend… His last, soft, almost inaudible words to me… Yes… Good times, Ken… Good times… together…

Yes… Bill… Good times… Together…

Continue your beautiful tour… My precious friend…

I first met Bill over lunch at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood when he was scouting California writers for AN‘s about-to-launch West Coast edition. Even though I tried to regale him with the latest LA architecture world happenings, everything I tried to tell him about he already knew. I must have told him at least one thing he didn’t know because soon enough I had the dubious distinction of becoming the inaugural Eavesdrop columnist for the West Coast edition. Writing for AN gave me a crash-course in L.A. design, sent me to cover glamorous parties I would have never been invited to, and introduced me to lifelong friends. Bill was eternally generous with his contacts and always quick to make a personal introduction. On my first trip to the Venice Biennale, I got nervous walking into a reception where I knew no one, staring into a sea of architects peering back at me over their lucite-framed glasses. But at the center of it all, there was Bill, waving me over, rearranging chairs, offering the last of a cold bottle of white and welcoming me with a big hug, making me feel like I belonged. I’m forever indebted to Bill’s generosity, which changed my life and so many others.

I knew Bill in Florence in the summer of 1969. We were both University of California students, though at the time I was a Ph.D candidate in English at the Santa Barbara campus. We were there to learn Italian and to experience of much of Italian life and culture as possible. We also had a lot of fun. His handsome, Peter Fonda looks got him a long way. Ladies were most interested in him, and he loved regaling us with memories of the marvelous meals people treated him to as he hitchhiked around Tuscany. He took up with a lovely German girl in Florence who was there to learn Italian in order to become a translator. Previously, she had been a sort of girlfriend of mine. No stress or bad feelings ensued from this triangle—in fact, it was all a laugh. For me, Bill was just one delightful aspect of a lovely summer in Firenze.

I met Bill in 2005, when I first started working as a junior editor for AN after five years as an editor of architectural monographs at the now defunct Edizioni Press. The paper was still being run out of Bill’s famous loft—a space that in and of itself, and quite like Bill himself, embodied and emanated everything I thought life in New York City ought to be: cultured, patinated, and cool. My background was in creative writing and literature, and I had hoped to wind up as a staff writer at the New Yorker or Harper’s while hammering out the next great American novel, or whatever. Working on architectural publications had been sort of a stopgap, something to do while I chipped away at my real dreams. It was joining AN, and meeting Bill, that changed my perspective. It was Bill who introduced me to architecture’s utopian aspirations, who pointed out that the development community did not always have the public’s best interests in minds, and who showed me that architecture, even and perhaps especially unbuilt architecture, could be wielded as criticism, like a novel or a poem. Through his example I came to understand that learning about, thinking about, and writing about architecture could be a whole life, and a great life at that.

AN really was like a family in those early days, with Diana and Bill standing in as mommy and daddy. And as with real family, during the ten years I worked for them we often took each other for granted, quarreled bitterly, wished we had never laid eyes on each other—all the signs of true love. I wouldn’t trade a minute of it. I only wish I could have been there at the end, to let Bill know just how much he influenced my little life.

Bill was a true mensch—always generous, kind, smart, funny, always there for you, whether it was an emergency boiler repair at the Greenport house or the best fish market on the North Fork or, well, just about anything. One of my fondest memories though was typical Bill, as it just sorta happened. By some strange confluence of factors, we both found ourselves in San Francisco on the same day. My wife, Julie Lasky, was attending a conference, and I was minding our daughter, then maybe 3 years old, pushing her up and down the hills in her stroller. Bill came to my rescue, proposing a meeting—starting at, I think, Tadich’s, for the petrale sole—and then off to the marina for a windswept walk along the water, the Golden Gate Bridge looming in the background. Along the way Bill provided an architectural tour of S.F., including some long-forgotten shingled-wood Julia Morgan houses in Presidio Heights, or something like that. It was a lovely day, all in all. So Bill. We will miss him. Love to Diana and Halle.

I met Diana in Texas before I moved to New York, before she moved to New York, before Bill. When she met Bill, she asked me to meet him, and I wanted to check him out. The first time I remember meeting him was at the loft. I thought he was perhaps the most interesting person I was ever introduced to. I imagined myself in a Broadway play, Bill the leading actor, always having more than one thing going on. Characters coming in and out. Who was in the back room? Who might you meet in the morning at the fabulous dining table that was also a piece of art? I remember Bill joyfully yelling up or down for the elevator that you had operate yourself. The loft was the stage, one that needed to be thousands of square feet to hold Bill (and his stuff). Bill had a guide he made for visitors, just so they would not miss the “only” place to get fresh bread or the right takeout. Once my wife and I were visiting Bill and Diana and got to stay one night at the loft; I eerily recall trying to go to sleep, exhausted, lying back, and staring out the huge windows at the World Trade Center, still illuminated. This was New York, unlike anywhere else I had ever been, like Bill, unique and captivating.

For over a decade, Bill Menking and I were fellow travelers in design; whenever I found myself in his company the night brightened. He wanted to know what I was doing, and I think he wanted to know what everyone was doing. Curiosity is a life-force he had in spades—along with passion and enthusiasm and good humor (as far as I could see anyway). Twice I went to him with a design issue that I thought was urgent, and twice he took on my enthusiasm to share his version of it with his audience. I am so glad that he was at the center of that web. Bill’s openness, engagement, and good spirit were a public treasure we won’t replace. Thank you, Bill, for enriching my corner of the world.

I am heartbroken to lose Bill Menking, a shining star not only of our field, but of Tuesday morning History-Theory classes at Pratt Institute. Our team of faculty and students adored Bill. His sparkling wit, wry humor, critical eye, and enthusiasm for cities, ideas, and radicality of all forms illuminated our mornings. In spite of his busy schedule and many projects, he always made time for his students and colleagues, and we will all greatly miss the way he would linger over sentences and plans, opening up their potentials and futures.

Like so many others here, I benefitted enormously from Bill’s letter-writing, support, enthusiasm, critical questions, and mentorship. His amazing work curating the American Pavilion of the 2008 Venice Biennale marked a field-wide refocusing on politically and socially engaged work, one that gave my generation of thinkers and architects great hope and a sense of possibility for the future. I’m so glad Bill got to both spark and live in that future, at least for a while. And I hope we can all channel his adventurous, experimental, loving spirit as we find our way through this strange time.

Looking for photos of Bill I realized that I knew him a long time before digital imagery. We must met in the late ’80s or early ’90s, and ever since then, we were always in contact. I never thought of New York without thinking of him. After Jeff [Derksen] and I got married spontaneously at NY City Hall, Bill invited us to stay at his remarkable loft. He immediately liked Jeff, and we all continued to have great conversations about art, architectural and design history, food, people, and cities. Later, my connection with Bill spread to other cities, as he was the greatest, and most generous, social connector. Bill introduced me to Michael Sorkin when he was teaching in Vienna. We also met Dagmar during Pratt’s studios in Berlin and Milano, where, along with students, we toured the Expo and Prada Foundation together. But the most important connection Bill enthusiastically established for me was to Wolfgang Förster. The Vienna Model exhibition, which Wolfgang, Bill, Helmut [Weber], Jeff, and I began working on in 2013, was, and still is, a wonderfully engaged and necessary project. Not only did it establish our friendship, but it continues to make a difference in pushing the idea of social housing—most recently, in Vancouver! The exhibition will be opening in L.A. this fall, and we had made plans to all meet there, with the desire to add a few days to go to Palm Springs and stay at a fabulous friend’s house by Albert Frey (as Jeff, Helmut, and I had done on a previous occasion). It was during Modernist Week, but rather than touring the city, we just enjoyed a whole afternoon at the house and the pool. It was such a pleasure to share Bill’s enthusiasm of being in a good place—architecturally and socially.

Bill noted to me early on that “architects are really well-meaning and are taught in schools to make the world a better place,” so it didn’t take long for him to inspire leaders to step up when faced with an injustice. After learning of the blind eye towards forced labor in the architecture and construction sector at our second anniversary at Grace Farms, he immediately shook my hand and said he would start a working group with me—“Yes, let’s do this!” And did he ever. Bill contributed to many ethical movements in his lifetime, and capped them off by putting his iconic stamp on forced labor with me/us in the building materials supply chain as a problem we should collectively address. The resulting impact of changes to come in the design and building process will bring freedom and raise living standards for countless people.

While working together, a conversation with Bill spanned many topics without hubris. I felt like I was getting a master class on the side and always a true sense of what he was enduring as a friend. He always carried on with incredible strength. I will miss his capacious mind, fun spirit and how he rallies with you. He would expect us to carry on and create this radical paradigm shift with even more fervor. Peace, my friend.

Losing Bill Menking, at the height of pandemic “social distancing,” is both unbearably sad and perversely ironic. His presence in our cultural environment was one of boundless sociability and generosity. During this period of compulsory isolation, his passing has magnified the value of his gregarious personality and integrative vision within the architecture profession. Bill’s vast number of professional triumphs have been acknowledged by international colleagues over the past few weeks; so, I prefer to focus on our personal friendship and its infinitely rewarding contributions to my life.

The core values of Bill’s global success as a publisher were based on his unique view of “idea communication.” The architecture scene, during the advent of The Architect’s Newspaper in 2003, was over-saturated with glossy publications that extolled the virtues of conventional aesthetic and technical accomplishment. Their graphic formats favored a kind of illustrative slickness…mostly dedicated to real estate values, orthodox design principles, and high-end advertising materials. Bill’s alternative was predicated on his prophetic instincts concerning the need for a source of challenging polemic and newsworthy reportage in the design world. The mainstream architectural media—by marginalizing such territories as design diversity, controversial aesthetic, provocative theories, emerging talent, professional gossip, polemical discourse and humanistic narrative—were generally overlooking the “good stuff.” AN provided a voice for the underground. While continuing to credit the development community and its predilection for commercial towers, the Newspaper gave equal exposure to visionaries who, for example, offered such varied proposals as underwater habitats, floating cities, straw bale housing, and, most importantly, revelations based on pure theory. Bill’s breadth of curiosity and passion for innovation became the foundation of our friendship. It was his respect for conceptual ideas and his capacity to ferret them out, discuss them in depth, and celebrate their sources in AN that fueled our dialogues and sustained my deepest admiration over the past 15 years.

While the architecture world abounds with intellectual ferment—especially in academia—Bill brought an entirely different sensibility to this discourse. Whereas the ubiquitous design symposia format could be a mind-numbing bore—he invariably offered a hospitable, down-to-earth, and unassuming atmosphere for any forum of ideas. Coupled with his frequently self-effacing humor and enjoyment of revelry, the discussion of a topic like deconstructivism—similar to the unpretentious platform of AN itself—could be transformed into a joyfully integrative evening of polemic and partying.

Bill’s joie de vivre and appreciation of lively discourse consumed every aspect of his personal and professional life. These attributes were applied to his teaching at Pratt, his leadership in publishing, his organization of cultural events, his lectures and conferences, and, especially, his charitable concern for the needs of students and colleagues. His social life demonstrated a considerable capacity for entertainment; but, in many ways, it disguised his depth of feeling for the challenges and hardships of others. At 87 and handicapped for the past few years, I have been a grateful recipient of Bill’s benevolence on multiple levels.

Over the last few years, Bill’s health issues also revealed his amazing capacity for optimism in the face of adversity. When offered the possibility of a new “miracle cure” for lymphoma he plunged into treatment with rekindled faith, even though it came with an indeterminate potential for success. During the early phases of this remedial process, we frequently discussed his trust in medical science and a checklist of new initiatives in architecture, needed for progressive thinking, and a better future. Up to his final days and the ultimate failure of this cancer cure, Bill always maintained his personal buoyancy and avant-garde outlook. To the very end, he reinforced my favorite quote from Oscar Wilde: “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.”

Of those who have died during the current crisis, the most personal for me was Bill Menking, cofounder of The Architect’s Newspaper in the U.S. Actually, he died of a long-term illness rather than the virus, but currently, deaths seem somehow to merge…

Meetings with Bill were, for this Londoner, as likely to be in any city other than the two we mainly inhabited. Hanging out in Los Angeles during the AIA Convention meant visiting the indoor Mexican meat market and checking out the (then) unloved downtown buildings, whose origins and architects Bill could describe in detail. Checking out his temporary Malibu residence was a delight. Needless to say, we had the services of a chauffeured limo.

Las Vegas, also the location for a memorable AIA Convention, was the occasion for Bill’s renewal of wedding vows (as it turned out optimism trumped reality) with AN’s co-founder Mrs. Bill Menking, better known as Diana Darling (cue Hello Darling jokes). The event took place in the Little White Chapel which had recently hosted the marriage of Britney Spears. I should say I am not making this up; my role that evening was to supervise the photography and make sure the two happy couples (the other being friends of Bill and Diana, also renewing) looked the part for the snapper. I suggested everyone shouted architrave as the shutter snapped. It seemed to have the desired effect…

In Miami for a World Architecture Festival reconnaissance trip, Jeremy Melvin and I had the pleasure of meeting Bill, by coincidence in town at the same time, and benefiting from his reminiscences of working as art director on the TV series Miami Vice—we visited the building where he had an apartment during the making of the series—and introductions to his impeccable contacts.

In Venice for the Biennale, Bill always seemed at home; somehow impeccably informed about who was doing what and which shows to visit or avoid, he was the brilliant convivial companion who made the Biennale, and life, seem easy.

We will be forever grateful for the support he and The Architect’s Newspaper gave us when we launched World Architecture Festival in 2008, which began we with a reception in NYC organized by Bill, where David Adjaye gave a welcome speech. A frequent judge in locations including Barcelona, Singapore, and Berlin, Bill’s presence and support was a kind of imprimatur for us.

Following so soon after the death of Michael Sorkin, also a great WAF supporter, Bill’s passing makes NYC seem a lesser place. It will of course revive, as both would have wanted, but it won’t be the same.

Too much sad news of late. To which is now added The Architect’s Newspaper founder and editor Bill Menking dying of complications to the bioengineered cure for the cancer from which he’d suffered for many years. Last year, it seemed he’d been truly rid of the cancerous cells occupying his bloodstream. A miraculous experimental treatment seemed to have rescued Bill—the cancer was 100 percent gone. So characteristically of Bill, he’d got into the test-phase protocol for this frontline treatment because he’d been at a dinner party and a doctor, whom he’d never laid eyes on before, hooked him up.

Anyone who knew Bill well knew that, despite his California roots, he considered himself a New Yorker-for-life, of the inveterate variety who knows the cracks in the sidewalks, and the pace of the signals along too many streets, which he’d plied daily for four-plus decades. But Bill never truly left California. He always had an open road and a wide vista ahead of him—a piece of the remaining epic of the California grange, limitless, fraught, unyielding, generous. Qualities Bill imbibed and embodied.

Quite simply, Bill had a magical charm with people—a western twang that hid his sharp memory and quick intellect. His great talent and art was in bringing us together, disparate, far-flung, seeming incompatible temperaments could always find rapport at Bill’s splendid dining room table in his voluminous loft in Tribeca. I especially recall one evening when I’d just come into town and Bill’s regular guest, Michael Webb of Archigram, was settling in at the table for a post-prandial drawing session. We’d all been gabbing away about who-knows-what ’60s radicalism, when Michael pulled out his drawing kit, walked over to the wall near Bill’s front door, and removed a drawing Michael had been tinkering with for years, so Bill said. Late into the night, Michael worked with a masterful, steading hand, inking black lines that needed completion. How like Bill it was to have an incomparable artist laboring away at his dining room table—contentedly, happily, delightedly.

Bill brought out the comradely quality in all of us. He united us beneath that tall, white-top, electric buzz cut, and the endless outpouring of encyclopedic knowledge, world-wide friendships, flypaper memory of places to eat. He loved to eat. And, then, as you were leaving, he’d hand you a jar of home-canned tomatoes, grown in the garden of his beloved homestead in Greenport, out on the North Fork, where he’d tool around in his near-mint 1974 Alfa Romeo GTV. And that was it. Hardly ever a good bye. Just, “Okay, see ya” as the door closed behind you.

See ya, Bill. And miss you, too.

I first met Bill when we were both working for a downtown studio called the Total Design Group in the early 1980s. Claude Samton, brother of the more famous Peter (of Gruzen Samton), was the major domo of the collective. There were a lot of young architects there at the time, working between other jobs in a kind of gig-economy precursor. It was crazy and fun, mainly involved in a study of subway stations for the MTA. It gave us a chance to tour the city underground, popping up in Brooklyn and Queens for a look at the real New York.

Among the youngsters, Bill and I were fish out of water: He had just come from California, where he grew up in the farming town of Stockton; I was raised in suburban Bellevue, Washington, coming east to get both my undergraduate and graduate degrees. Neither of us knew much about New York, except that we had to be there in order to experience the excitement and energy that were pulsing through the metropolis. Ronald Reagan had just been elected, punk rock was emerging, and soon John Lennon would lose his life in a senseless act of violence. I think that we shared a pretty unique experience of seeing the city at a key transition point; it stayed with us and colored our subsequent views as historians.

We lost track of each other when I departed to teach in Houston and he went off to Europe for a few years. Eventually we both landed jobs teaching back in New York and were able to touch base through mutual friends. I knew that he had a secure position at Pratt, but frankly never expected him to stay in academia—he was much too unruly for that. When he began AN, I was delighted to know that he could range as freely as he wished in writing about the environment. The fact that he, like Joan Didion, was a Californian, was an advantage in the early years of the new millennium.

I got to write book reviews and a few other pieces for Bill’s “newspaper” over the years, and he was always an active and incisive editor of my work. When we last saw each other a few years ago for lunch, he was the same energetic, curious soul I had known 40 years before. Despite living through 9/11 and the 2008 recession, he remained unjaded and unfazed—I wish I could say the same. It isn’t remotely fair that cancer should take him now, when we need him more than ever.

The architecture world has lost a significant figure. An educator, critic, provocateur with a great sense of humor. Always curious and willing to help at any time. He was considered one of the most articulate and insightful writers on architecture. We will miss his big smile at the Glass House where he frequently attended events. He was kind, wise, and generous. We will greatly miss him.

The world is so much poorer and so much less interesting with the passing of Bill Menking. Unfortunately, I was not a close friend of Bill’s, but I was the next best thing: I was one of the thousands of people in his conversational orbit. I never failed to be astonished by what Bill had done, and what he knew. The interlocking genealogies of who did what and who worked for whom going back decades were at his fingertips as though he had it all written down on the back of a giant envelope. He was one of those indispensable people who served as the collective memory and conscience of our field. The idea that Bill is no longer with us is very hard to process: How do we carry on without him?

I met Bill and Diana in the ’90s through Sabine Bitter after they returned from London with Halle. There were the Lispenard Loft dinners, events at Columbia and Storefront, and intermittent communications since I left the city. After his invitation to Facades Miami 2017, we became closer friends.

You could know the essence of Bill just by looking at him. He stood tall and lean, a proud Leo exuding confidence with no excess. While strikingly handsome and stylishly cool, he was a modest, down-to-earth guy. Bill was a thoughtful thinker, an eloquent communicator, charismatic with a positive disposition. His brilliance was an academic intelligence and curiosity combined with the ever-present concern for the human condition and how architecture and cities affect it. Bill was actively engaged in our realm of architecture in a humane way with a generosity of spirit; open-minded, open-handed, and open-hearted was he.

His smile was friendly and sincere. His energy was vital and exciting. Bill Menking’s eyes looked into you and he listened. He was interested in all people, what they were doing, how they felt, and what they thought. He was an engaging conversationalist, whether as a moderator or in private chats. Behind the glasses was not the typical architecture historian. Those of us who became architects because of the radical visionaries such as Bucky Fuller, Archigram, Superstudio, and Ant Farm, and to do social housing, found a simpatico in Bill. As sexy and fiery as his vintage red Italian car, Bill was a real Alpha Romeo. So youthful in spirit, I never thought about nor knew his actual age.

In the COVID-19 lonely liminal space between life and death, Bill remained witty and hopeful, looking forward until the last week. He wanted to swim in the ocean. Take a night drive along the sea on the North Fork in his Alfa. Have great wine and great food and great fun. His bucket list was “Villa Malaparte, a week in Naples. Right now a week in Vals.” Such a lovely soul and attractive man. Bill Menking was the real deal! He was always “getting better but weak.” How could he get better? He was already the best.

Rest in Nirvana Bill.

I met Bill Menking and Diana Darling in 2002 when the launch of The Architect’s Newspaper, The Center for Architecture, and Open House New York were all in planning. It was an exciting time for New York’s architecture and design community and Bill and Diana helped provide the media support and local intelligence and contacts that helped fuel Open House New York’s successful launch.

Over the years Bill supported Open House New York in many roles from board member to fundraiser to researcher to connector of people and places. Bill didn’t just offer suggestions to others—he rolled up his sleeves and did the hard work—and he did it not just for Open House New York but for many wonderful organizations that serve our community and our city. His generosity, kindness, and sense of humor, and his belief in the power of architecture, design, and public engagement were a constant inspiration for me.

From the editorial page to the board meeting, Bill championed noble causes and ideas. I am grateful for his friendship and for his example.

Of all the things people can thank Bill for—and there are many—I can thank him for dragging me into the gutter. I met Bill through Cathy Ho in 2002 when they and Diana Darling were in the final stages of planning The Architect’s Newspaper. Before I knew it, they’d somehow talked me into becoming the world’s first architecture gossip columnist (or so we liked to call it). As a freelancer, I wrote the Eavesdrop column for its first three, mischievous years, and I’m still amazed sometimes at what Bill let me get away with. While it took longer than I expected for that first cease-and-desist letter to arrive—as always, Bill was totally unfazed—let’s just say that the column’s reputation got me blacklisted by Dow Jones (long story) and slapped with an ultimatum by The New York Times, whose editors informed me I could continue writing for them, or Eavesdrop, but not both. As a young writer who’d had his fun in the darker arts of architecture journalism, I chose the Times, and Bill never held it against me.

After all, Bill was someone whose only agenda seemed to be his love of architecture, in all its messiness, and with that came his unconditional support for those of us who shared it. For years, even after I’d moved halfway around the world, I could count on his encouragement; the occasional, unsolicited e-mail telling me about a job opening in New York he thought I should go for; the out-of-nowhere phone call suggesting that I take up teaching (which I’ve since done) “because it’s a good gig.” An entire generation of architecture and design writers, curators, and practitioners knows exactly what I’m talking about. Bill was a bottomless well of generosity, and it built your confidence.

One of the last acquisitions I made as a curator at M+, the new museum opening next year in Hong Kong, was the Archigram archive. This was, of course, right up Bill’s alley. He knew about it beforehand for well over a year—maybe even two or three—and was itching to break the news, but held out on the promise that I would tell him, first thing, as soon as it was official. In the end, a British publication somehow got wind and broke the story. Again, Bill was unruffled, and immediately set to work on the Archigram oral histories we’d talked about him doing, even as his health was failing. Sadly, that’s a project that will now never be completed—though I can easily imagine him still working at it, totally unfazed, in that big Instant City in the sky.

Bill was a new known person of mine. But his smile and his sharp mind transformed a new introduction into a kind young friendship. I met Bill at Grace Farms in New Canaan, CT, and since then he was the first smile entering in one of our meeting of the Grace Farms Foundation, fighting against the forced labor, the new kind of slavery, around the globe.

Despite my not-very-good English, and the challenging task all the group is trying to achieve, Bill had the talent to be a self-explanatory advocate and one of my most deep architectural mentors.

Thank you, and goodbye, Bill. Now you can observe your loved cities and buildings from above.

Oh, my. It’s hard to imagine New York City without Bill. Even though we met at UC Berkeley in the fall of 1967, his open invitation to the Lispenard Loft was always there, long after I returned to my roots in Wisconsin and he landed in Manhattan to make a name for himself. My dorm friends and I needed a fourth for our two-bedroom apartment on College Avenue, so Greg Poulos brought his Stockton High School friend Bill to be his roommate. Bill and I connected pretty quickly and soon found ourselves marching together to protest the Vietnam War at the Oakland draft board. The next week we went to his mom’s house in Stockton to pick up her console TV so we could host Star Trek parties in our apartment and watch it in living color—a campus rarity in those days. He was rarely at the apartment, though—he had a job bussing tables at a fraternity, he had architecture projects to complete, he had to conjugate Italian verbs (a monumental struggle).

My girlfriend Shirley came to Berkeley the following year, and Bill liked her even more than he liked me. (He had a thing for smart Jewish women.) We lost track of Bill for a few years after graduation, but, thankfully, Bill didn’t let go of relationships. Sometime in the ’70s, he called to discuss the big Cal-Stanford football game and told us about this giant loft apartment he had and that we were welcome anytime. I’ve lost count of the visits by now. My children have stayed there, my grandchildren met Bill. We used to step over drunks passed out in the entry hall to get to the hand-operated freight elevator, getting glimpses of the sweat shops on the six floors below his penthouse.

In those days, Bill was giving architecture tours of New York in his own Mercedes sightseeing bus. I’ll never forget the night he took the two of us on our own private tour. We ended up stopping in Brooklyn to watch the lights of Manhattan sparkle through the panoramic windows of that magic bus. Bill’s passion for the city and love of storytelling made it very clear he was in the right place at the right time. He was full of energy, bigger than life, and open to everyone. We’ve been fortunate to be a small part of his big life for over 50 years.

New York will never be the same without Bill.

Bill’s splendid relationship to the field—urbane, yet grounded, like The Architect’s Newspaper—was of standout importance in my own life when I was feeling cold feet about my move to the States. I told him I had a job offer in California at a campus I’d never heard of. Bill wrung out of me where I was thinking of heading. “Davis?!” said Bill—the usual response of people hearing the dullest name ever for a town. I cringe. But it turned out that Bill was a Central Valley boy, and uniquely placed among anyone I knew to have an informed opinion. “Oh! Davis is niiiiice.” The reassurance made all the difference, and I still appreciate it. Other things too, like conversations and hang-outs, an overnight stay, some research leads, and an association with The Architect’s Newspaper. But the encouragement to give Davis a go made my kids happy, so it stands out. It simply never occurred to me that someone with Bill’s youthfulness and generosity wouldn’t be around forever, so it’s only now that I’m tying together the little threads we shared.

I graduated from Pratt in 2005. I was a student in their first professional M. Arch I program. While I knew of Bill at the time and his venture AN, we did not become close until several years later, when I started writing book reviews for AN. Bill and I shared the same taste in experimental movements, especially modernism and the avant-garde. He sent me the books he was interested in having me review, or sometimes we picked them together and I’d go to the office. He sat, surrounded by the many books of interest—there were so many that I couldn’t see him behind his desk. I loved looking through options together, and so long as I hit the word count, Bill let me write what I liked. I spent so much time on the reviews—and I did that because I wanted to write something that would excite Bill and do our mutual interests justice. This seeking to find significance in the radical is what bound us, as well as the desire to express ourselves uniquely. I would run into Bill at events from time to time, and we would chat, but it was the special relationship we had—both of us architects but also writer and editor—that I will cherish forever. The excitement and enthusiasm Bill brought to everything he found interesting is inspiring. I think of Bill often… (And I’ll miss his ellipses in our correspondence.)

Bill was always my go-to, a tremendous source of esoteric architectural and design knowledge. From the cat at the Pratt Engine Room to having a meal together in Tel Aviv at an Open House Worldwide conference to our last exchange about a Joe Colombo–designed coffee cup–Bill’s pantomath curiosity and his generosity in sharing it with whomever he engaged with was truly a remarkable gift. His friendship was something to be both cherished and relished.

I consider him to be the quintessential Cali-to-New York transplant: as a Cali gal myself, it was always inspirational to hear his reminiscences about the fading Berkeley beatnik days and his early activism, about how he was suddenly a part of the precarious mise-en-scène of New York City in the ’70s. I am sure that I will continue to meet and be inspired by all of you who were lucky enough to know him.

Not only has the architecture and design world lost a brilliant and influential mensch, we have also lost a truly singular voice for the madding crowd, who insisted that the people must continually advocate for a healthy and humanistic built environment. As cofounder of The Architect’s Newspaper, Bill created a important and impactful legacy.

Godspeed to Bill on his ultimate journey off this mortal coil.

Bill, was a stand-up guy. When he and his students were in Berlin, they would drop by our studio to hang out and see what we were up to. Bill would engage the students by discussing what practice was and what we were doing, just making it relevant for them. We’d reciprocate and sit in on juries of his and Dagmar’s (Richter).

His humor was deadpan and that made him a perfect partner for a road trip to Ithaca or for a drink in Venice or Kensington Gardens. He was everywhere.

He would go to bat for you. AN was a news outlet, but he wasn’t afraid to use it as an instrument to say what he thought, even if it was against the grain. A real journalist. He taught me about Superstudio and the history that was important to him. A source of endless ideas.

A mensch. One of kind. Irreplaceable.

I knew Bill for so many years now, first as a young practitioner, then as an academic, and now as Chair at Penn. He had in every capacity added so much weight and intellect and fun, that it is impossible to even imagine him not being here anymore. His presence will always be felt and of course his memory will remain. But for all of us left behind it is a hard pill to swallow. My warmest condolences go to Diana and their daughter, and the staff of AN.

Just thinking back on the often strange or unusual memories and experiences we shared: as juror at the AN‘s 2015 Best Of Design Awards jury; being together with him and Rob Rogers on the New Rochelle building committee; having him attend events at Penn and getting his feedback; his defending of architects and architecture against misreadings or misjudgments of their talents and work (think of the “Architects with Attitude” article of 2010). We at Penn are going to miss all of this, and I think it will take a long time to get over this loss in our community. Thank you, Bill.

Bill was so gracious to me when, in 2012, I was part of a group trying to save John M. Johansen’s Mummer (Stage Center) Theater in Oklahoma City. He was the only person outside the city who would listen to me, and he gave me a platform to talk about what a terrible idea it was to destroy it. I learned so much from him, and his direction changed the way I work and think. I will be forever grateful.

I met Bill Menking probably a year or two after he launched The Architect’s Newspaper. I had been involved in a couple of long-deceased architectural journals such as Skyline and was familiar with the typical trajectory these things take. But the paper was lively. It seemed to have a close finger on the pulse of what was happening in the profession. The writing was good, which is often rare in architectural journalism. I signed on immediately as a subscriber and was later honored to be invited to contribute some pieces (mainly book reviews). At the time I thought to myself how anyone could hope to sustain a free journal about architecture that was aimed at an architectural audience. This is such a slow-moving profession, and I worried how he could keep it up. But it was so good and filled a void. He proved me wrong.

Bill became a great friend, colleague, and supporter of ours. The HarlemNOW map, for instance, had its start in a class of his at Pratt in 2008. He asked me to give a talk on cultural mapping and suggest a project like downtown for his students to work on. Harlem was undergoing a renaissance; that was a natural choice. I gave a program and some suggestions and went back to the office. I didn’t hear from him again for a couple of months. He called me one day and asked me to lunch. He brought a big shopping bag with him, which turned out to be filled with the students’ projects. So, I realized that I had to rearrange my schedule to use their content and create this map. I hired some interns and spent the following summer formalizing their research into the HarlemNOW map. We launched with Margaret Castillo (as AIANY President) and handed Governor Patterson the first copy (in Harlem, of course). That was probably the first of many projects we collaborated on over the past ten (or more) years.

When we came up with the idea for the Cocktails and Conversations series, I immediately reached out to Bill. We signed him on. He had a few suggestions for speakers and immediately volunteered to be a pairing, choosing Richard Weller. He thought that the resulting book was a great idea and wrote a letter in support of it to the AIANY that kickstarted that publication.

I have Bill to thank for many of the wonderful things I have accomplished professionally, which wouldn’t have happened without his encouragement, support, enthusiasm, and intelligence. I shall miss him.

If you never met Bill Menking, you would have liked him.

Bill was a patron of architecture and architects. Surprisingly free of cynicism and arrogance for someone so influential, Bill was just wonderful. An enthusiast. Professionally, Bill was an unparalleled editor and publisher. He took the format of the trade journal and turned it into something else: a place for architects to exchange knowledge, news, and opinions. It was an honor to write for Bill; he always improved my writing, and by extension, my intellect.

I liked Bill, a lot in fact. Bill was fun, brilliant, witty, and the life of the party, any party. He was always inviting friends to drinks, dinners, openings, launches. He was always quick to support a new idea, but also, I think, quite suspicious of false prophets and cheap tricks.

Bill was singular. And what made him most singular perhaps were all the Bills that made up who he was. Off the top of my head, I know of at least a dozen different permutations of the mercurial, ebullient Bill Menking. Here are a few of them, in no particular order.

Scholar Bill

Bill was, if nothing else, a great student of architecture. Like some great students, Bill was a great scholar. Like all great scholars, Bill was also, inevitably, an expert. In his case, in the post-war Florentine radical avant-garde (Superstudio, Archizoom, et al.), was a specialist subject that held Bill’s interest and led him to produce a series of excellent publications and exhibitions in New York and elsewhere.

Insider/Outsider Bill

Bill was too wise to be cynical and too zany to fully inhabit his insider status. I always felt that what was most charming about Bill was his relentless optimism, his fan-like love of the field. Bill was simultaneously urbane and goofy, incisive and disarming, worldly and somehow also always decent and kind. He managed to maintain enough of himself in the game to remain an outsider, but, really, Bill was the ultimate insider.

Prankster Bill

Bill, I suspect, disliked the sorts of affectations and caprices that float around the architectural community. He poked fun at them mercilessly and loved to endlessly stir the pot. He did so less out of contempt for arrogance and more as a public service to humble the over-privileged and over-rated in our field.

Enthusiast Bill

Bill was always intrigued by good architecture, always supportive of visionary work. He supported anything public-facing, like the urban design competitions that we ran at SCI-Arc with Sam Lubell in the late 2000s. I don’t think there was an architectural event in L.A. that Bill missed when he was in town, and when he was in town, his emails and texts inviting as many people as he could rally to AN events were sweet and unfaltering.

Mensch Bill

Bill also supported my efforts to re-think architectural education a few years ago, running a piece that introduced an effort of mine to start a new sort of school. He also ran a thoughtfully critical response by my colleague and friend Todd Gannon. This was the fair-minded thing to do. Bill then joined our Board of Advisors and was even in his praise and fair in his criticisms. Bill was clearly a mensch.

Innovator Bill

Bill had a penetrating vision of architectural media that few quite fully understood. He was a savant. Bill understood—a full decade before others—that digital media did not spell out the end of architectural journalism as we knew it, but was instead a new beginning. He saw a future for writing about our profession and then, with the remarkable Diana Darling, he went out and built it. The Architect’s Newspaper is a testament to Bill’s vision and he will live on through it.

Goodbye, Bill.

You will be very, very missed.

I will never forget the walks I took with Bill Menking. One time he took a class of 60 students on a walking tour of Midtown Manhattan, exploring the history of public space in New York. I thought to myself that this must be the equivalent of the Socratic peripatetic school in Athens. Afterwards, I mapped the walk to keep a record of it. Next time, Bill and I took a walk in Trastevere in Rome. He had stopped in Rome on his way to the Venice Biennial. He presented me with an informal and precious account of Italian architecture of the ’70s. The third time, we took a quick walk in Manhattan—it was hard to catch up to his speed sometimes—from Tribeca to downtown and we talked about things, buildings, objects, from the detail of a building to the Olivetti typewriter. For him buildings and objects had stories, and architecture and design were newsworthy. Nowadays, I don’t get to take walks, and our public spaces are changing from physical ones to virtual ones. I am saddened that we will not hear Bill’s voice about this change and which walks to take once we get back to our streets.

I met Bill in Venice in 2008 when he curated the Biennale Pavilion of the United States. Leanne Mella introduced us, and I was all too happy to help him organize a cocktail party at my uncle’s converted chapel near the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Bill loved Italy, and it was easy to find common ground, the first being Superstudio (my wife and I had just sponsored Adolfo Natalini as an honorary FAIA), Alfa Romeos, second, and, of course, food. We kept in touch over the years even though I did not manage to see him often. The last time was when he passed through London and I picked a restaurant that I knew he would like. We drank, and as was usual with Bill, the conversation was lively, ranging from architecture gossip to politics. The long lunch ended too soon! His life ended too soon, and he will be missed by the many he touched! Thank you, Bill!

Bill and my late husband Bill Woods met when they were asked to teach city planning to architecture students at Pratt. They were two like-minded souls for planning and urban design and became instant friends, as did Diana and I. We traveled together many times. Bill Menking was the best person to explore a new place with—he always knew the coolest places to eat and had magical entree to obscure venues of art and architecture. In 1994 he and Bill spoke at a planning convention in Phoenix, Arizona. Afterwards, we traveled on what was essentially my and Bill Woods’s honeymoon to Arcosanti, Taliensen West, and Sedona to see the Red Rocks (and find the best enchiladas).

The following year we went to Paris and then to London, where we stayed in a flat that friends of the Menkingses had swapped for the latter’s NYC loft. That winter there was a “Siberian wind” in Europe. It was so cold the four of us wore our coats indoors and huddled in the steamy loo at night for warmth. Diana and I protested like crazy, but Bill would not offend his friends by letting them know we were suffering (while they, in turn, sweated in the overheated NYC apt). Today, Diana and I would have ditched the guys for a hotel, but back then we soldiered along with them and of course had a lot of laughs. Bill wrote Bill Woods’s obit in AN when he passed away in 2017 and hosted his memorial at Hunter College with Gina Pollara with generosity and grace. I will miss him forever. Love to Diana and Halle.

I never had the opportunity to meet bill, but have been an avid reader of AN since its inception. Thank you, Bill, for your great work, and we hope that AN can carry on the legacy of the wonderful work that Bill started and AN‘s staff and contributors have produced over the years.

Seventeen years ago, after the hard drive on my computer crashed and I lost all my old emails, one of the first messages I received on my new computer, and still have, was a “hey Joan” from Cathy Ho. It was an invitation to a meeting on Lispenard St. with Bill, Diana, and others to float the idea of a new publication they were contemplating calling A&D News. By August 2003, The Architect’s Newspaper was launched, and, after agreeing to be a board member, I not only had the privilege and pleasure of being comped thereafter, but also of being in contact with Bill every so often about an article he wanted me to write or something else. The next message I received from him, later that month, was an obituary for Cedric Price, forwarded from The Guardian. Bill’s book on Superstudio (with Peter Lang) also came out that same year and gave new life to those radical Italians. Over the next decade and a half, the engaged and ethical stances he took in his editorials and other activities likewise animated architectural discourse and gave it a humane raison d’être. Becoming a lynchpin in architecture’s critical ecosystem, Bill and AN continued to evolve with assurance and increasingly national ambition. Most recently, about a year ago, Bill and I were in touch about collaborating on an article on Trump Tower Moscow. Both of us were eager to write it but by the time I returned from a trip overseas, Bill was ill and the news cycle had moved on to the next Trump outrage. That, sad to say, was the last time we exchanged messages. It was much, much too soon. Thank you, Bill, for your friendship and your crucial voice. Now your loss is bound up with this sad season we’re living through.

Bill couldn’t help himself; he was just simply glamorous. It was in his bearing, his easy laugh and his generous nature, topped off by his physical stature and those good looks. That glamour, together with his incredible nose for the cultural moment and his unshakable moral sense, made him a kind of hero of the common man. I love that AN picture of him as a young organizer for the farm workers, like Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath. It says it all.

So much of what he did throughout his life was typified by this uncanny sense of the glamour of the good, and the power of the public, including his cofounding of AN and his work on the Venice Biennale. I was lucky enough to have been part of his foray in Venice as Commissioner of the U.S. Pavilion. It was a groundbreaker of an exhibition, the first to present American architecture from the community-based, bottom-up point of view he was passionate about. It was commissioned under Bush but, as he liked to say, it ushered in the Obama era.

AN has got Bill right with this open-source memorial where we can all, as equals, upload tribute. He would have loved it.

It was always a treat to be in Bill’s company, as everyone who knew him can attest. Since my home is in Milan, we would see Bill on his various trips to Italy over the years. The year he curated the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale he was kind enough to send an invitation to the opening. How exciting it was to attend an affair held in the magical Peggy Guggenheim Museum. Another time, when he was over with Aaron Levy to interview Vittorio Gregotti, he kindly took me along as an interpreter even though Gregotti spoke excellent English.

Bill was my first friend to have an iPhone, and I knew it was imperative to have one when he showed me a drawing app. An excellent cook, pasta with rucola and olives was one of his specialties. How many people can come to Italy and teach Italians how to cook? Only Bill.

One year Bill came over for the Salone del Mobile wearing his dapper bright yellow slicker. After he had already returned home, a photograph depicting a bird’s-eye view of the fair was featured in the newspaper, with people looking like ants congregated here and there. Wouldn’t you know, smack dab in the middle was an exceptionally tall ant in a bright yellow coat. It made me smile. That was Bill, always at the center of the action.

Bill Menking was a friend and a mentor, to me and to countless others whom he taught and convened, and to those who read him on a regular basis. Along with a team of dedicated contributors, Bill created and nourished The Architect’s Newspaper, a vital source of design news and criticism founded in New York City, which went on to span the country. Whether in conversation or through written word, Bill’s candor and curiosity were palpably indefatigable. A fearless critic and instigator, Bill kept us all informed and on our toes. Bill will be dearly missed by the architectural community and by me personally.

It was today that I received the bad news from New York that Bill Menking passed away. I knew for two weeks that his long and courageous fight against his cancer was coming to an end, and that Bill was going to die at home surrounded by his beloved ones. I had known Bill since our cooperation on The Vienna Model at the New York Austrian Cultural Forum in 2013, and we had then met several times in different places all over the world. He was looking forward to the opening of our The Vienna Model 2 exhibition in Los Angeles in fall 2020. Bill’s enormous knowledge of architecture and housing and his engagement with socially oriented urban planning and housing have impressed thousands of experts everywhere. People like Bill Menking never really die: He will continue to inspire us in our efforts to humanize the world of architecture and urban planning. At the same time, we will miss him and his voice. My thoughts at this moment are with his family and closest friends and colleagues. We shall miss you, Bill!

I got to know Bill at the CUNY Graduate Center, where I taught in the Art History PhD program until 2011 and he completed all the requirements for a doctoral degree except for the dissertation. Determined to finish his doctorate, he often contacted me for advice and we’d meet for lunch to discuss his topic, Archigram, for which he had an obvious affinity. This was vividly demonstrated by his several publications and exhibitions on this visionary group, whose quintessential expression of the utopian 1960s spirit in architecture closely paralleled Bill’s own sense of adventure and experimentation. Although I repeatedly told him that I would love to supervise his dissertation, I also reassured him, always unsuccessfully, that he really did not need a PhD because he had already established such a brilliant career outside academe and accomplished so much without the formal validation of a doctorate. Nonetheless I am grateful that his determined persistence, another of his distinctive qualities, kept us in regular contact until very recently, and I will miss him tremendously.

Simply put, Bill Menking pulled off one of the great miracles in the postmillennial information industry with his inspired conception, expert execution, and careful nurturing of The Architect’s Newspaper, which he cofounded in 2003 with his wife and mainstay, Diana Darling. In a period of severe retrenchment and distressing decline among even the most established and authoritative American publishing companies—especially the ever-dwindling number specializing in architecture and design, and increasingly so after the market crash of 2008—Bill established and maintained AN as a major journalistic force in a stunning reversal of prevalent trends.

This anomalous success story is due not least of all to his and Diana’s keen understanding of how to strike a viable financial balance between electronic and print modes, an equation that has somehow continued to elude far more extravagantly funded news organizations. Indeed, The Architect’s Newspaper has become so indispensable to the profession and its followers that one wonders how we ever got along without it.

For good or ill, every periodical I’ve written for throughout my 45-year career has had its tone indelibly set by its editor-in-chief, in a spectrum of seriousness that has ranged from the elevated literary humanism of Robert Silvers at The New York Review of Books to the brash celebrity buzz of Vanity Fair under Tina Brown. No less so, Bill Menking infused AN with his own personal qualities—an insatiable curiosity, absolute moral clarity, and a gentle mischievousness that never curdled into cruelty. Thus you always know when you’re reading The Architect’s Newspaper, even when it’s excerpted in transmissions far from its home base.

After Bill ceded day-to-day oversight of AN to others, his personal values continued to prevail in every issue, a clear sign of his strong imprint as founder/auteur, and a rare vestige now that anyone with access to social media considers herself or himself a voice to be reckoned with. But as receptive as he was to encouraging young talent, he was no less welcoming to long-established writers, who are never immune from the rebuffs of publications in perpetual search of novelty.

In 2018, I wrote an obituary on Robert Venturi for another paper, but an editor there made deep cuts, deeming much of it too mawkishly sentimental. Among the deletions were the names of the devoted team of caregivers who’d seen Bob through his years of dementia, and though I wanted them to be duly recognized for their extraordinary devotion, I assented to the edit against my better judgment so that my tribute could run at all.

When I realized that there was enough of my original version left over to comprise another, entirely self-contained obituary, I offered that reworked text to Bill, who unhesitatingly accepted and posted it within hours. To my delight, the response to it on the AN website outstripped that of the earlier, bowdlerized piece. This is the kind of support and vindication that a writer never forgets.

Throughout the long and harrowing medical ordeal that he endured bravely and uncomplainingly, Bill retained his characteristic optimism and faith in the future. His death is a terrible loss to what Frank Lloyd Wright called the cause of architecture, which Bill exemplified through his undaunted commitment to building a better world and encouraging others to join in that task.

The last time I saw Bill was April 2019, the last time I visited New York. I stayed at his place, perhaps for the last time, where I was welcomed so many times. We talked while he was on his bed, where he spent most of his time already. I asked him if America has changed or if I had changed, since I immigrated here more than 50 years ago. Surely everything can change after a half century, but he resolutely answered that America has changed. I asked this question because he was an American, in the land where I feel welcomed less and less. Bill was the real American, a gentle giant who lived by honesty and truth, like the Americans that I looked up to when I left Korea, when it was a third-world country. We lost a great American, a real American who made me feel like an American, someone who once made me think that this is a great country. Without Bill, I feel less American.