Disclaimer: AN is the media partner for Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect

The Bronx Museum of the Arts’ Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect is sprawling, playfully curated, free to enter, and well suited for display in the borough that inspired so much of the artist’s work. Showcasing over one hundred of Matta-Clark’s pieces, the exhibition features films, prints, sculptures, and a series of interactive dialogues.

Matta-Clark’s art, centered on a ravaged New York City in the 1970s, gains power when viewed in the proper historical context. As abandoned properties were torn down across the Bronx and crime rates soared, residents felt disempowered; Jonathan Mahler famously wrote that the city was in the middle of “fiscal and spiritual crisis.”

Trained as an architect, Matta-Clark lashed out at gentrification, economic stratification, and the physical divisions caused by capitalism in the ways that he knew best. A founding member of Anarchitecture, a group that criticized the excesses of architecture, Matta-Clark’s work frequently critiqued the historical destruction caused by modernist architecture as an outgrowth of capitalism.

The show’s organizers are no strangers to the material. Antonio Sergio Bessa, writer, poet, curator, and the Bronx Museum’s director of curatorial and educational programs, partnered with Jessamyn Fiore, the co-director of the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and frequent exhibitor of his work, for Anarchitect.

Anarchitect may be a linear show, but that only enhances the experience. Each room progressively builds upon the last, and the importance of Matta-Clark’s reverence for cuts, holes, and site-specific installations and his focus on exposing the hidden reveals itself over time. Following a gradual introduction to the artist’s fascination with negative space, spontaneity, and the emergence of chaos from ordered systems, the show’s layout pushes viewers along an entwined timeline of Matta-Clark’s work and the evolution of his political views.

Perhaps the best primer on Matta-Clark’s worldview is the film that visitors must pass through before reaching the main gallery. Substrait, a 1976 consolidation of shorter works, follows the artist and collaborators as they spelunk below the Croton Aqueduct, Grand Central Terminal, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and other New York landmarks. Despite the crushing darkness and massive, alien scale of the infrastructure surrounding them, the film emphasizes the essential nature of these spaces.

New York, so frequently thought of as a “vertical” city, relies on the horizontal voids below; one guest describes them as the hot arteries of the city, delivering life. Without the foundations, steam systems, and tunnels that deliver clean water, upward expansion would be impossible, much in the same way that the rich rely on the working class “beneath” them.

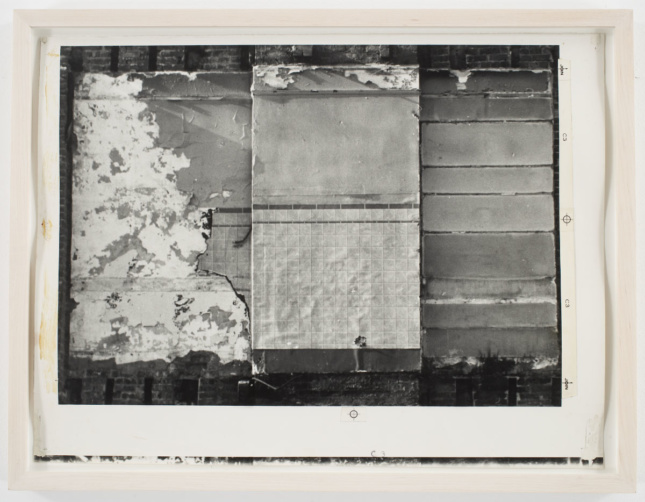

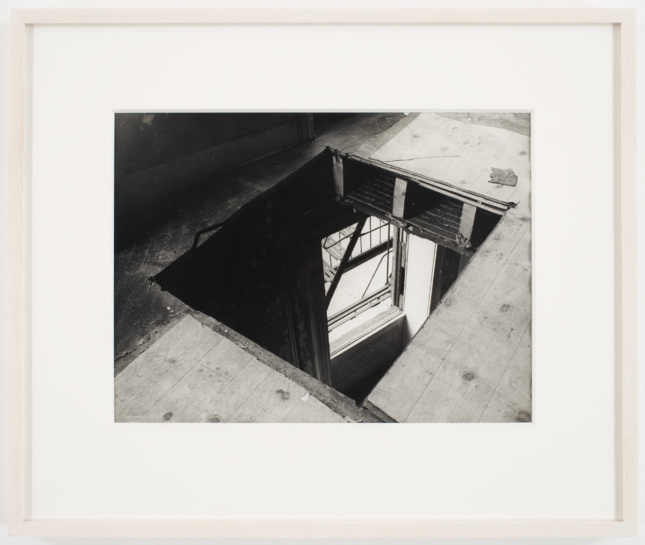

Inside the main gallery space, Bronx Floors sees Matta-Clark’s usage of geometric holes cut in the floors or walls of condemned Bronx buildings to examine the building from angles unintended by their designers. In altering the “ideal” form of the building, Matta-Clark attempted to show Bronx residents that they could reclaim some form of control over the built environment, even as the city was indifferently tearing it down around them. The contrast of horizontal and vertical is repeated here, as holes intersect with “established” doorways and windows, giving viewers the impression of seeing from a mystical, impossible viewpoint.

Wrapping the edges of the exhibit are rarely seen black-and-white prints of the artist’s graffiti photography, many of which he colored by hand after developing. The placement is a neat trick, and creates an interior-exterior contrast that enhances the message; the graffiti, like the voids they surround, were used to reclaim slivers of a city that seemed actively hostile to its poorest residents.

The most monumental of Matta-Clark’s work is saved for last, as the final room contains photos, diagrams and large-scale projections of both Conical Intersect and Day’s End, presented back to back with emphasis on the connection between both projects.

Conical Intersect, one of Matta-Clark’s most famous works, saw Anarchitecture carving a conical hole through a pair of abandoned 17th-century buildings in Paris, with the rising Centre Georges Pompidou as a backdrop. Through stitched-together panoramic photos, viewers are able to understand both the massive scale of the carvings, as well as the specifically constructed views they afforded.

This protest against historical destruction in light of France’s drive for “urban renewal” drew obvious parallels with development in New York. Realized the same year as Conical Intersect (and part of the reason Matta-Clark fled to France in the first place) and placed next to it, Day’s End saw the artist cutting massive holes in an abandoned warehouse on the Hudson pier.

Envisioned as a “sun-and-water temple,” Matta-Clark’s attempt at reclaiming an unused plot of land as a public park was adaptive reuse before the term went mainstream, guerrilla urbanism done literally under threat of arrest, meant to expose the hypocrisy of keeping the waterfront inaccessible to the public. Now, over 40 years later, the Whitney Museum is resurrecting an ethereal version of the project to float over the Hudson River.

At the end of Anarchitect, one faces a troubling truth. Although the Bronx’s fortunes have improved since the 1970s, artists and politicians are still debating how to address the same issues of inequality and urban policy failures that Matta-Clark sought to highlight. As New York enacts urban renewal programs in an effort to curb an affordable housing crisis, and homelessness rises to historic levels, Anarchitect’s look back at the city’s troubled past is startlingly relevant.

Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect

The Bronx Museum of the Arts

1040 Grand Concourse

Through April 8, 2018