Marcel Duchamp Prize-winning artist Cyprien Gaillard’s film Nightlife (2015), currently on view for the first time in the United States at Gladstone Gallery in New York, is a portrait of the living city. Gaillard, who was born in Paris and lives and works between New York and Berlin, practices across media, including photo, film, and sculpture. He is known for his meditations on memory, history, and failure—including work on the legacy and present of modern architecture. His latest film, Nightlife, was filmed with advanced imaging techniques and drones, and the camera flows and glides between close-up, abstract shots to floating arial views with ease.

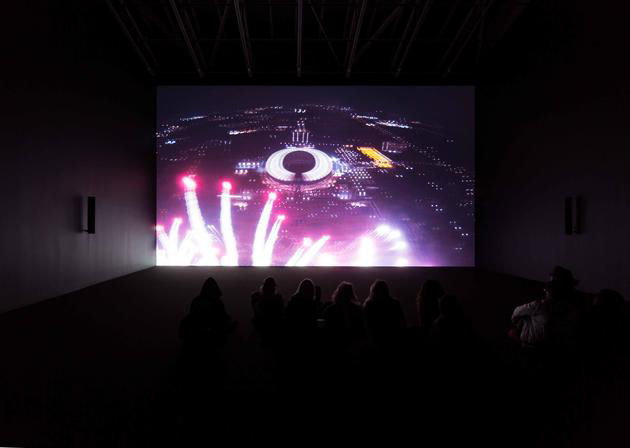

Upon entering the gallery, a nautilus shell in a recessed light box mounted in a black wall marks the entrance to the screening area. Viewers are offered 3-D glasses, which enhance the hallucinatory, ecstatic nature of the piece.

Though comprising seemingly abstract shots—swaying trees, fireworks, city streets, aerial views of buildings, all, of course, shot at night—the film is deeply allegorical, telling a complex history of revolution and resistance through objects, plants, and buildings that live and breathe as characters.

Presented without caption or narration, the film advances in what might be described as four acts through Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Berlin, coming full circle in Cleveland again. The film opens on an almost indiscernible closeup of a plant before moving on to Rodin’s The Thinker, outside the Cleveland Museum of Art. The spinning camera revels in the sculpture’s apparent decay, the result of a 1970 bombing by the radical left-wing organization the Weather Underground.

Nightlife then advances to Los Angeles, where it depicts dancing, rioting trees on the streets of the city—primarily the Hollywood Juniper, a non-native species that has been a recurring motif in Gaillard’s work. Shored up against the architectural forms, the trees not only trouble the boundaries of natural and artificial, but also evoke notions of indigeneity, migration, and belonging. The trees’ movements might also be read more explicitly as a reference to the so-called L.A. riots of 1992 and to other forms of civil action and resistance.

Though arguably all of Nightlife depicts the city as protagonist, the most explicitly architectural moment is the third act, which features the Berlin Olympiastadion. Built for the 1936 Olympics, the stadium served as a monument to the Third Reich. It now functions as a space for a variety of events, including an annual fireworks competition, the Pyronale, which is displayed in the film in explosive technicolor.

The film returns to Cleveland, landing on American runner Jesse Owens’s Olympic oak tree planted at the Ford Rhodes High School. Owens, whose four gold medal wins as a black athlete at the 1936 Olympics in Nazi Germany flew in the face the Third Reich’s extensive racist propaganda campaign, was awarded an oak sapling for each of his gold medals (the oak tree serves as a symbol of Germany).

In lieu of the sound of its settings, the film loops a sample of Alton Ellis’s Blackman’s Word (1969) throughout, its repetition pulling the viewer into Nightlife’s self-contained world even more completely and unifying the disparate scenes. (Originally featuring the refrain “I was born a loser,” it was re-recorded in 1971 as “I was born a winner.” Critically, both versions feature in the film.)

Not merely a vibrant portrait of cities at night, Nightlife traces the residue of history left on the landscape—be it “natural” or built.

Nightlife originally appeared at Sprüth Magers in Berlin and is on view at Gladstone Gallery through April 14th.

Cyprien Gaillard: Nightlife

Gladstone Gallery, 530 West 21st Street,New York, NY

Through April 14th