Steven Holl Architects’ (SHA) expansion of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.—titled The REACH—is expected to open to the public at the beginning of September. The $250-million expansion consists of a 4.6-acre complex with three semi-submerged pavilions rising with bright-white cast-in-place concrete and opaque glass facades. Notably, SHA’s design features crinkled concrete sound-dampening walls that could potentially be used on facades.

The use of concrete integrates the addition with the material palette of the preexisting Edward Durell Stone–designed complex, albeit the new buildings break from the rectilinearity of the older pagoda-like buildings by using soaring curves.

- Facade

Manufacturer

Fitzgerald Formliners (Rubber Molds)

Lane Construction (Cast-in-place concrete)

- Architect

Steven Holl Architects

BNIM (Associate Architect)

- Facade

Installer

Lane Construction - Facade

Consultant

Reg Hough (Concrete Consultant)

Silman (Structural Engineer)

- Location

Washington, D.C. - Date of

Completion

2019 - System

Structural Concrete - Products

Custom-fabricated rubber molds.

A significant aspect of the Kennedy Center expansion is the insertion of performance and rehearsal spaces to increase the Center’s cultural offerings. The challenge? The hardness of concrete, combined with its flush surface, inherently hurts acoustic performance. To solve this quandary SHA Senior Partner Chris McVoy and Senior Associate Garrick Ambrose got to work in the studio’s in-house workshop.

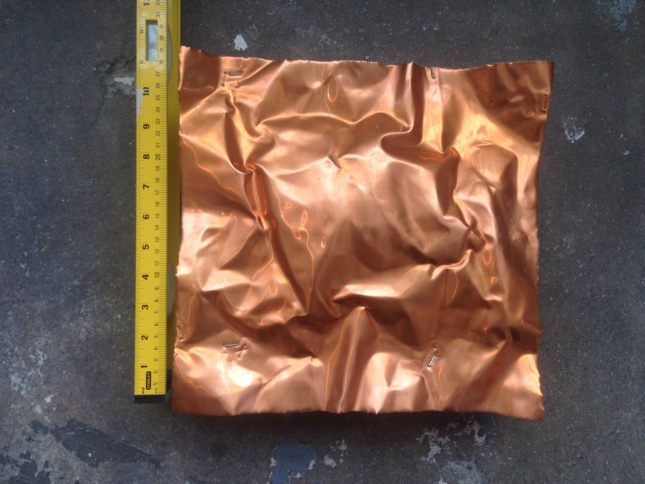

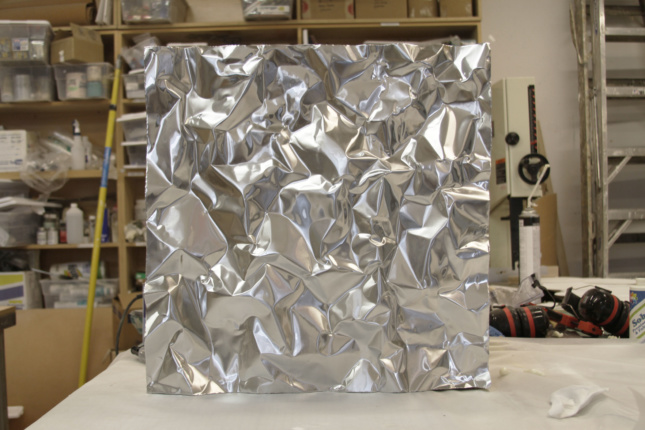

“The process started with making small one-foot by one-foot crinkled metal samples in our shop to determine the appropriate size and depth of the crinkle pattern that worked best visually and acoustically,” Ambrose said. “After the pattern was finalized, we took a large 10-foot by 4-foot sheet of aluminum, thin enough to form by hand, and crinkled it in our shop. The crinkled metal panel was then fastened to a wooden framework and sprayed with foam insulation on the back to freeze the pattern in place before it was sent to Fitzgerald Formliners in California where elastomeric rubber molds were created.”

One of the challenges of the early prototyping was sourcing pieces of aluminum large enough to reduce seams across the surface whilst still being hand pliable. Luckily, manufacturer Alucoil donated the firm a large roll of aluminum. The research phase, from the creation of small mock-ups in-house to the first concrete pours on site, took approximately two-and-a-half years.

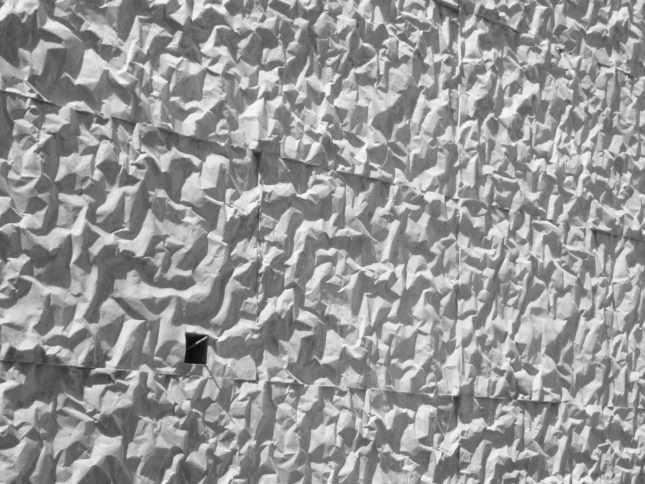

SHA worked closely with acoustician David Harvey to determine the optimal depth of the relief, which ultimately settled between one-and-a-half and two inches.

Following fabrication, the rubber molds were transported to the construction site and fastened to the rest of the formwork prior to the concrete pour. To avoid the visible repetition of the crinkled pattern across the performance spaces, the construction team flipped and rotated the rubber molds. The result is a remarkably detailed concrete finish with laps of light and shadow that not only acoustically dampens the space but is integrated into the complex’s overall structure.

Garrick Ambrose will be present The REACH at Facades+ Washington D.C. on February 20 as part of the “Placemaking and Monumentality: Opaque Facade Strategies” panel.