Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker has signed a law that authorizes the sale of Helmut Jahn’s controversial postmodern icon, the James R. Thompson Center. Postmodern buildings have only recently become eligible for landmark status, a fact that highlights the need to preserve significant buildings that have years to go before reaching a minimum of 50 years old.

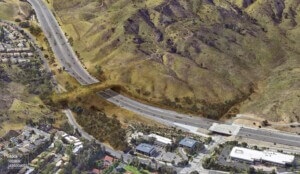

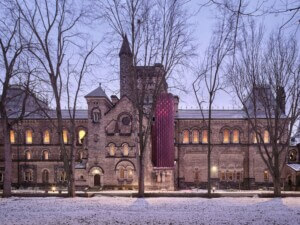

The center is located prominently in Chicago’s Loop at 100 West Randolph Street, where it takes up an entire city block, with a Chicago Transit Authority “L” train station nestled underneath. Stout and glassy, the massive building opened in 1985 as the home of state government offices. It was named after Illinois’s longest-serving governor, James R. Thompson, who chose Jahn’s then-futuristic design. Aiming to invoke ideas of “an open government,” Jahn designed a glass-encased 17-story atrium and a large exterior plaza in a bid to create contemporary large public spaces.

Chicagoans either love it or hate it. The story of the Thompson Center is a political saga that could end in a daring feat of conservation or a sad finale of destruction. Preservationists have been rallying and petitioning for the building to achieve landmark status since the first mention of its possible demise in 2007, when Governor Rod Blagojevich said he was interested in selling it. However, since the building is known for its major maintenance issues, like heating and cooling problems and physical deterioration, it will likely be demolished rather than repurposed.

The Architect’s Newspaper‘s Midwest contributor Jamie Evelyn Goldsborough reached out to major figures in the Chicago architecture and preservation community for their takes on the controversy.

Alexander Eisenschmidt, designer and architectural theorist, associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Architecture:

Jahn’s Thompson Center is certainly a quintessential Chicago construct. Not so much for its often cited but rarely understood postmodernism, but because of its urban and infrastructural theater. In fact, reducing it to its material, color, and formal palette (its architecture) diminishes its public function (its urbanism). After all, the building is a subway stop, an elevated train station, a pedway intersection, an interior marketplace, a food court concourse, an exterior plaza, and the list goes on—a kind of city-extension that inhales and breathes public life. In an age of ever-expanding privatization, aggressive outsourcing, and shrinking government investment in public services and facilities, the sale of the Thompson Center is yet another instance of the lack of inventiveness and a blind belief in quick fixes (not unlike Chicago’s disastrous parking meter sell-off). But it’s also a mistake for architects to focus on preservation. There is the potential for crafting solutions for a productive (even lucrative) re-, dis-, mis-, trans-, and cross-use of this piece of the city.

John Ronan, architect, professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture:

The State of Illinois Building should be saved (and repurposed). It’s one of the few good examples of postmodern architecture in Chicago from a period of architectural history that was not particularly kind to the city.

Bob Somol, design critic and theorist, professor and director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago:

The debate over the shaky future of a once-futurist ruin raises paradoxical questions about postmodern preservation and the ongoing privatization of the public realm. What happens when a rhetorical ruin becomes a literal ruin within 30 years of its completion, when a project that inaugurated a mixed public-private model of government itself falls victim to economic expediency? Helmut Jahn’s 1985 Thompson Center was an awkward building at an awkward time, appearing after faith in public monuments had waned, but before the rise of iconic spectacles. It was the James Stirling building that Chicago never got, typical of many atrocities of the ’80s that attempted the shotgun marriage of high tech and historicism. The Thompson Center remains Chicago’s only legitimate heir to this thankfully aborted legacy. And for all of these reasons and more, we should keep the starship boldly going.

Stanley Tigerman, architect:

I don’t want to comment about it, because I will say something bad.

Ellen Grimes, associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

It’s our own lesson in John Portman/Jon Jerde postmodernism, repurposed for retail politics. I love it! It makes the ’80s urban in a way that didn’t happen with similar buildings of the period. There’s nothing like floating up the escalator from the Red Line into a monumental atrium that smells like burgers and falafel.

To save it, [Governor] Pritzker should use it as the emblematic policy initiative in reforming the state’s pathetic finances. He should landmark it, lease it to a casino/hotel operator, and send the profits straight into the state’s underfunded mass transit budget. (Imagine playing the slot machines as you get off the train.) That way, we get to keep the thing, and get some money out of it, and it’s climate friendly. And Thompson gets the monument he deserves.

Iker Gil, architect, editor-in-chief of MAS Context:

It is a significant building with a truly remarkable interior public space. Unlike most buildings, here we have one that welcomes people and celebrates public space. We need to think beyond its current state of neglect and envision its potential. It can become a vibrant 24-7 space with the addition of expected and odd uses that can be combined unconventionally. The building has unique characteristics and it should remain a unique place, but, as Tim Samuelson would say, the building is in a period of aesthetic limbo. It’s not old enough to be appreciated; there is no historic perspective. Given time, care, and a programmatic overhaul, it would find its place in the history of the city. Chicago can’t afford to continue to demolish unique buildings only to replace them with generic ones for a quick economic return. This practice won’t solve Chicago’s structural issues, and the city will lose its assets and identity.

Nathan Eddy, filmmaker, Starship Chicago:

The Thompson Center shouldn’t just be an official landmark for Chicago; it should also be listed on the National Register of Historic Places alongside Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building or the Chicago Federal Center by Mies van der Rohe.

I defy anyone to stand in the Thompson Center’s launchpad rotunda and not be moved by that magical, mirrored-glass cyclone of space. It courses with power and drama and excitement and an expansive, glittering optimism. It doesn’t look dated to thousands of young people who gasp when they walk into it—to them it looks like the future.

Are we really prepared to give up this prime, publicly owned forum in the civic heart of Chicago for a bargain-basement price? To be replaced with what?—a mute glass box designed not by an architect but by some false acceptance rate algorithm? And perhaps—if we’re good—a handful of half-hearted privately owned public spaces? Sounds like small plans to me.

Judith De Jong, architect and urban designer, associate professor and associate dean for academic programs at the School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Chicago:

Built 20 years apart, and each very much of its respective time, the Brutalist Netsch campus at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and the postmodern Thompson Center are unlikely bedfellows. However, both are hard-to-love forms of architecture that are seemingly out of style, and both once modeled important new forms of public access to public institutions that are perhaps even more important today.

The Netsch campus, which opened in early 1965, was a new model of an urban public university, making higher education accessible to a wide range of new audiences. Rather than mimic the pastoral forms of the traditionally rural public university (the model of which was the University of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson), Walter Netsch and his team from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill sought to materialize a new expression of public education through urban and architectural design. Conceptualized as a pebble dropped in a pond, representing “knowledge spreading out,” the dense inner rings of campus contained the shared lecture halls and classroom buildings, flanked by the library and the student union, while outer rings contained discipline-specific buildings. The campus was connected throughout by raised walkways—human highways designed for a projected enrollment of 32,000 students—that came together in a great public amphitheater called the Circle Forum at the literal and conceptual center. Photographs of the campus at the time show the Forum’s use as an important space of daily life. Buildings were also carefully arranged to shape urban parks and plazas for public student life across the site.

The Thompson Center, which opened in 1985, was a new model of access to urban public government. Rather than mimic the classical grandeur of the Illinois State Capitol Building, Helmut Jahn and his team from Murphy/Jahn Architects materialized a new expression of state governance through an enormous interior atrium—a lopped off rotunda—limned by 16 floors of the mostly open offices of public employees. The atrium was intended as an active, new, year-round public “plaza” in the middle of downtown, enabled by “retail” government services like the Department of Motor Vehicles, as well as shops, a food court, and integrated access to the Chicago Transit Authority trains. At the Thompson Center, government was meant to be as accessible and transparent as the building itself.

As experiments in new forms of public institutions, both UIC and the Thompson Center had their issues, all of which were or are solvable, should the political will exist. At UIC, complaints about the walkways, framed through concerns about maintenance, safety, and a lack of “green,” led to their eventual demolition in the 1990s, taking the Circle Forum amphitheater with them. Likewise, the environmental and maintenance issues at the Thompson Center are well-documented, and just as Netsch provided possible solutions to issues at UIC that were ignored, Jahn has provided possible options for the Thompson Center that are being ignored. But whereas at UIC the form of the campus was diminished by the loss of the Circle Forum, its overall organization and many of its original buildings remain basically intact. Moreover, UIC continues to be a state institution, and as such, the architecture and urban design remain a powerful symbol of public access to higher education. While I believe strongly that a robust public life can and does occur in privately owned spaces, which could perhaps be the case at the Thompson Center should it be sold to a sympathetic owner, much more is at stake here. In an era of relentless privatization, where public institutions are under sustained attack, the sale of the Thompson Center would be a significant blow to the idea of public access to state government, and raises a much more fundamental question: Is the public institution, rather than its architecture, going out

of style?