Imagine arriving at the Sheep Meadow in Central Park intending to lie on a blanket in the warm afternoon sun, as you have done many times before, only to find that there is no sunshine anymore. It has been blocked by a new tower just to the west more than twice the height of any building around it, including the 55-story Time Warner Center several blocks away. You look around and notice that more than half of the 15-acre lawn where you used to bask in sunlight is now in shadow.

The greatest urban park in this country is directly threatened by those who see it only from a distance. Just as Capability Brown cleared long vistas in front of grand estates, new Excessively Tall buildings turn Central Park into a landscape framed from above. As a result of these new giants, in a few years Central Park may well be unrecognizable and barren—like much of our environment, dying off and becoming extinct.

Our built environment, one that we architects designed, will have mortally damaged an Olmsted and Vaux masterpiece. The irony is that the new Excessively Talls (ETs), jacked up on stilts or interspersed with large and repetitive mechanical voids to increase their height over adjacent buildings and secure desirable park views, may ultimately lose their picturesque vistas. These multimillion-dollar investments may be responsible for the measured obliteration of New York City’s world-renowned park.

Developers whose new, faster construction methods have accelerated the emergence of a building type catering to the superrich have now launched insidious advertising campaigns showing off the “new” New York: a thicket of gleaming skinny towers. None of these projects have affordable units. Their ads boast park and river views from altitudes of 600 feet and higher (not all ETs are Supertalls, defined by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat as towers measuring over 984 feet high). But the parks they showcase, Central Park first among them, will continue to exist in name only. No bucolic pasture will remain in the Sheep Meadow, the carousel will be too cold to enjoy, the ball fields unplayable (grass dies in the dark), Wollman Rink gloomy and windy, Tavern on the Green in shadow all afternoon. The New York City Marathon’s slowest runners will be greeted at the finish line not by waning sunlight but by a giant shadow, courtesy of the latest addition to the Upper West Side, a forthcoming tower designed by Snøhetta on West 66th Street, less than 600 feet from the park.

The new ETs—many completed along 57th Street, now aptly nicknamed Billionaire’s Row—are also beginning to touch down wherever there is a view for sale and zoning doesn’t limit height, such as the remaining landing strip of underdeveloped properties between First and Second avenues with potential views of the East River and Long Island, and, most recently, on axis with St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where Gensler has designed a tower. Has anyone considered that natural light would no longer stream through the church’s stained glass? Whatever happened to protecting our heritage and neighborhoods with sensible planning and human-scale development?

ETs are catastrophic energy hogs, far worse than typical urban residential construction. Exaggerated floor-to-floor heights and full-floor apartments create a worst-case scenario for energy efficiency. Superskinny towers also have far more structural steel and concrete than is required to bear gravity loads because of the need to resist outsize wind loads. Local infrastructure (water, sewage, and power) is compromised, or service cut, because of the time needed to pump and discharge water and waste. And consider life-safety issues—how long will these buildings take to evacuate in an emergency, factoring in the time it takes to navigate multiple elevator banks, to rescue people in distress?

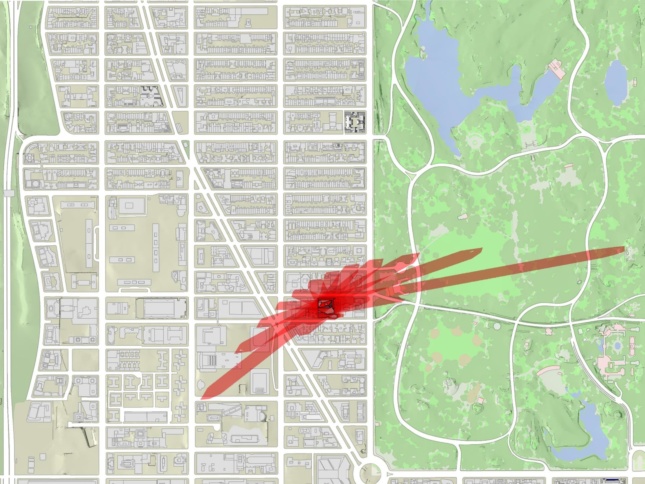

But the impact of ETs spreads far beyond their physical footprints, especially when they appear in numbers. Sophisticated software can conduct shadow studies on the cumulative effect of more than one ET on a city block. The East Side will soon have two towers between 62nd and 63rd streets, one fronting 2nd Avenue and the other on 3rd. Surrounding apartments left in their shadows will need artificial light all of the time, increasing demand on the power grid and our dependence on fossil fuels. And then there is the wind. While data retrieved from the study of a single ET may show that it has no negative effect, the cumulative wind tunnel effect produced by multiple ETs will quite possibly create impassable and turbulent streets, with vicious downdrafts caused by the Bernoulli effect (increased turbulence, or downdraft, as the wind hits a large facade).

The developers of these projects and some of our elected officials, unfortunately for us, have ignored the neighborhood residents affected. The public review process has become virtually nonexistent. Gone are community reviews, special permits, and even cursory notification to neighbors. The only way to find out how big these buildings are is by exhausting a Department of Buildings zoning challenge, then moving on to the Board of Standards and Appeals (Article 78), and finally, issuing an injunction. By then, the as-of-right ET will likely have entered construction, or worse, be built.

All is not bleak, as there are new regulations limiting the use of glass on tall buildings, thanks in part to the monitoring efforts of the Audubon Society, which has reported that millions of birds fly into such buildings every year because they can’t recognize a mirrored image. That may help.

Not since Central Park was practically devastated by neglect during the Beame administration in the mid-1970s has it been so direly threatened, but this time the danger is from without, not within. ETs and other out-of-scale development also place community and public gardens, pocket parks, and playgrounds at risk. It’s time for New Yorkers to rise up and insist on new restrictions to stop the indiscriminate abuse of light and air that could suffocate the city’s parks and their adjacent neighborhoods. To be sure, our skyline is rapidly changing, and there will be consequences, but the potential for irreversible damage demands a moratorium. To insist on more insightful planning is not “NIMBYism”—it is the professionals taking charge.

Page Cowley is founder of the New York architecture practice that bears her name and serves as chair of Landmark West!, a New York preservation nonprofit, as well as cochair of the Manhattan Community Board 7 Land Use Committee.

Peter Samton was managing and design partner of the New York architecture firm of Gruzen Samton, aka IBI/Gruzen Samton, and is a past president of the New York Chapter of the AIA. He now serves on Manhattan Community Board 7 Land Use and Preservation Committees.

Daniel Samton practices architecture as Samtondesign in Harlem, has worked at KPF and Gruzen Samton, specializes in sustainability, and is a certified passive house designer.