Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface.

—Donald Judd

I have made a place.

—Mark Rothko

Architects often say that the best clients are those who are most collaborative, but what if your client died decades ago? I think of our restorations of 101 Spring Street, Donald Judd’s home in New York City, and the Rothko Chapel in Houston as case studies in posthumous collaboration. At these remarkable sites, Judd and Rothko expanded the physical boundaries of sculpture and painting by creating carefully calibrated spatial relationships between art and its context. When we experience these places, we gain greater awareness of ourselves, of our connection to other people and the world around us. Yet the passage of time diminished their qualities, as the conditions needed to appreciate them changed. Sensitively engaging these sites required untangling a web of aesthetic, philosophical, administrative, technical, and constructional questions. Through our research-based methodology, we gathered and analyzed information (including archival documentation), conducted interviews, analyzed historical and existing conditions, and synthesized the work of specialists. This established the basis of a rigorous, iterative design process that aimed to yield a holistic strategy. Ultimately, our challenge as architects was to reconcile the artists’ original intentions with the ongoing missions of the cultural organizations that perpetuate their legacies.

Preservation and access

The space surrounding my work is crucial to it: As much thought has gone into the installation as into a piece itself.

—Donald Judd

We first encountered this unusual design problem when we were responsible for the restoration of 101 Spring Street, the five-story 1870 mercantile building that Judd occupied from 1968 to 1994. Here, he made what came to be known as his permanently installed spaces: site-specific installations of his art and that of his peers. He modified the cast-iron building and added new elements to create an unprecedented interaction between art and daily life. In the years following his untimely death, the deterioration of the building compromised Judd’s work and the Judd Foundation’s mission—on top of the fact that the building did not have a certificate of occupancy. Working closely over eight years with representatives of the foundation, we preserved the authentic experience Judd intended. Paradoxically, this required extensive modern technical infrastructure, such as fire suppression and life-safety systems, without which public access would not be possible. Completed in 2013, the painstaking effort touched nearly every part of the building, but the project’s success is measured by the extent to which our presence disappears in service of Judd’s vision.

Contemplation and action

We have here both a chapel and a monument; a place for worship and a memorial to a great leader. The association of these two remarkable sites should tell us over and over again that spiritual life and active life should remain united.

—Dominique de Menil

A current project, presently in construction, is the restoration of the Rothko Chapel and new architecture that supports the chapel’s expanded public programming. The Rothko Chapel is both a place and a program, comprising the union of patrons John and Dominique de Menil’s ecumenism and egalitarianism with Mark Rothko’s aspiration to create deep emotional connections through the immersive experience of his art. The chapel building, completed in 1971, is a locus for spiritual enlightenment through meditation in a space Rothko

defined through the integration of 14 monumental painted panels with their architectural context. The adjacent reflecting pool and Barnett Newman’s sculpture Broken Obelisk, dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr., symbolize the chapel’s mission to act as a platform for social justice through its programming, which promotes dialogue between people. The dialectic between contemplation and action, which is integral to the chapel’s institutional and architectural identity, is the basis of our design strategy. In this sense, we engage the de Menils as collaborators, too.

Restoring the sense of awe

A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer.

—Mark Rothko

Our goal for the chapel restoration is to reinstate a sense of awe in each guest along with a recognition of self, which is the basis of the chapel’s social mission. This self-recognition is constituted from the experience of Rothko’s interior, an octagonal space formed by his paintings, which are portals into voids of fluctuating opacity, color, and reflectivity illuminated by a central skylight. Although he determined all the key attributes of the chapel (prevailing over the wishes of Philip Johnson, who designed the building with Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry), Rothko never visited Houston and died before it was completed. Choosing daylight as the primary source of illumination, he did not anticipate the harsh Texas sun, which immediately began to damage the paintings and weaken the qualities that he had so rigorously studied in his New York studio. During the decades following the opening of the chapel, three attempts to block and filter daylight with baffles did not successfully address the need to control glare and brightness. The most significant element of the restoration is an innovative lighting strategy developed by George Sexton, which opens the interior space as it was originally conceived. This includes a new skylight with an array of angled louvers, each precisely oriented to distribute daylight more evenly to Rothko’s panels. When daylight is lower than needed to see the paintings, such as on a very cloudy day or at dusk, eight digital projectors concealed in a ring around the skylight provide subtle additional illumination. Other changes, including a redesigned entry sequence, will greatly improve the quality of the experience.

Mediating between the chapel and the neighborhood

…a reconciliation between the ordinary and the extraordinary in a dialectical relationship…

—Stephen Fox

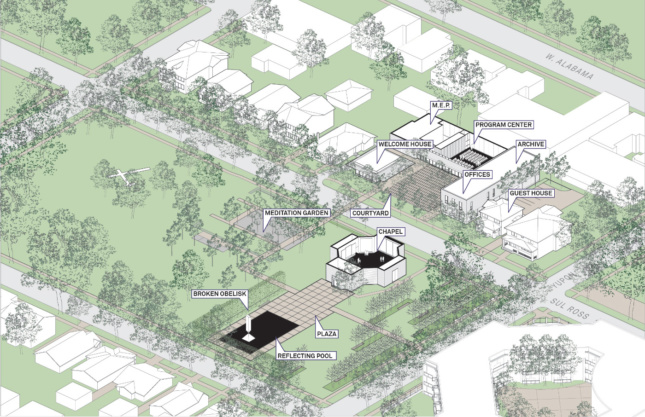

The new architecture for the chapel is grounded in both the singular power of its building and the unique character of the surrounding early-20th-century residential neighborhood, but does not overwhelm either of these contexts. This maintains the de Menils’ vision—the essence of the chapel’s identity as a program—to situate the sacred within daily life. A new landscape precinct, designed in collaboration with Nelson Byrd Woltz, is created by the removal of adjacent houses occupied by the chapel and the addition of new planting, paths, and plaza pavement. This affirms the chapel’s presence as a freestanding element within the larger open space shared with adjacent Menil Park on a block framed by a necklace of bungalows. Across Sul Ross Street, a new north campus comprises a welcome house, program center, and an administration and archive building that together define a public courtyard, which opens to the street. The scale and massing of these elements echo those of the adjacent residences, further bridging the neighborhood and the chapel. With glass walls shaded by a generous wood trellis, the porchlike welcome house is a resting place along the journey to and from the chapel. The program center, which includes a two-hundred-person meeting room, is pushed to the back of the courtyard to establish a buffer against larger development to the north. The administration and archive building aligns with the width and height of the chapel, which also sets the height of the program center.

The architectural expression of the north campus extends the site strategy. The simple building forms echo the chapel’s mass and are clad in gray wood siding that relates to the existing bungalows, which are all painted gray. This vertical and horizontal board-and-batten detailing provides a play of shadows, which integrates the architecture with the dappled light that passes through the tree canopy. A large, shaded glass wall visually connects the program center’s meeting room to the courtyard and the chapel across the street. The meeting room, whose outward-looking public orientation contrasts with the chapel’s inward focus, is defined by simply spanning laminated wood beams, gray plaster walls (which match the chapel), and a wood floor. It is equipped with concealed technical infrastructure to support a variety of events, including lectures, symposia, banquets, and workshops. The north wall of the meeting room is illuminated by a continuous skylight, which brightens the interior and enables views into the space from outside.

Unity

…one person is a unity, and somehow, after the long complex process, a work of art is a similar unity.

—Donald Judd

I have created a new kind of unity, a new method of achieving unity.

—Mark Rothko

The restoration of 101 Spring Street and the restoration and expansion of the Rothko Chapel are deeply informed by our engagement with both posthumous and living collaborators (including the artists’ children). Sometimes our work is invisible; often there are prominent new elements. Ultimately, everything is shaped by our judgment. We seek a reciprocity between existing and new architecture, a complex layering that balances deference and distinction. These projects inform our other current work, including the design of a new visitor center for Olana, the painter Fredric Church’s property in upstate New York, and the Dia Art Foundation’s spaces in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. Judd and Rothko used the word “unity” in describing their aspirations for art that encompasses the fullness of humanity’s relationship to the world. Dominique de Menil expressed her conviction that “spiritual life and active life should remain united.” Through these projects, we learned that inquiry and invention, grounded in empathy and humility, unite architecture with its past, present, and future cultural contexts.

Adam Yarinsky is a principal at ARO.