There is a cultural aversion to cycling in New York City.

At least, that’s the belief of one Lower Manhattan-based engineering firm with a plan to upgrade the network of biking opportunities in the city. Though recent news has reminded New Yorkers that cycling here is dangerous, there seems to be a less-than-friendly approach to changing the inefficient system despite it. Mayor Bill de Blasio has advocated for Vision Zero since he took office in 2013 and continues to push for net-zero carbon emissions across all five boroughs, yet the build-out of safe bike lanes has been incredibly slow and not very innovative.

Buro Ehring, a local studio that specializes in structures, facades, and fabrication, has envisioned a world where all this is different: New Yorkers can cycle underneath the Brooklyn Bridge instead of on top of it; an elevated bikeway lined with trees runs above Canal Street; 31st Street is completely and solely dedicated to pedestrians—no cars allowed. These speculative improvements, created under a masterplan called CycleNYC, would decrease commuting times, separate cyclists from vehicles, enhance air quality, and in turn, add joy to the art of bicycling in a major metropolis.

It’s not a far-reaching proposal. In fact, some of want they want to actualize is very doable. “CycleNYC at its core simply seeks to repurpose last century infrastructure and elevate it to meet the growing needs of New Yorkers,” said Andres De La Paz, a designer at Buro Ehring.

But in order to make a series of infrastructural, cultural, and formal moves that turns that aversion upside down—as the team at Buro Ehring aims to, it will take the help of city agencies, local community boards, alternative transit advocates, other design professionals, and maybe even CitiBike.

Here’s what they propose:

Greenways

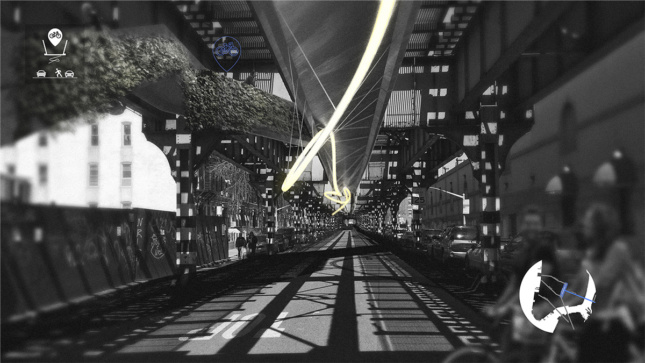

Arguably the most construction-heavy part of CycleNYC, greenways would require the build-out of elevated bike infrastructure above the city’s busiest east-to-west corridors. In a study, Buro Ehring found that the bike network running north to south in New York is much stronger than its perpendicular counterpart. To fix this problem, those busy axes would be relieved with an above-the-street cycling track. Remember Foster + Partners’ raised bike path for London? It’s like that, but possibly with less glass.

Buro Ehring reimagines New York’s most traffic-ridden (and most deadly) thoroughfares with this unique infrastructure. For context, Canal Street’s cycling track would span 5,843 feet starting from the Manhattan Bridge, Delancy Street’s path would stretch 9931 feet from the Williamsburg Bridge westward, and there would be similar structures on Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City, Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, Houston Street in Manhattan, as well as Myrtle Avenue and Sunset Park in Brooklyn. By calculating the exact measurements of these potential bike highways, Buro Ehring outlined the amount of material needed to build these greenways as well.

One of the biggest benefits to this idea—besides the increased safety of cycling out of sight from cars—would be the advanced purification of the surrounding atmosphere. Buro Ehring proposes that the sustainable materials used to build these greenways include titanium-painted panels that absorb respiratory pollutants, as well as self-cleaning protective rain screens. Artificial LED lights also installed along the way could help grow the tree screens that envelope the legs and walls of the tracks.

Pathways

Just as buildings get expanded and retrofitted to accommodate new programming, so can New York’s bridges and elevated subway lines, according to CycleNYC. The goal is to increase interborough connectivity and remediate air pollution that cyclists experience when they cross the East River next to idle cars and their heart rate rises due to the gradual incline. Buro Ehring proposes using existing pieces of infrastructure and building cycling tracks underneath them in order to provide healthier links. Think: Manhattan Bridge with a bike path hanging below the highway instead of structured on its northern side as it is now.

In another example, the Queensborough Bridge could feature a pathway that’s 6561 feet long and creates a smoother connection to Roosevelt Island and Cornell Tech. The bike path would spiral down onto the small island and stop commuters from having to cross into Queens before taking the pedestrian bridge or the tram from Manhattan.

Pedestrian Walkways

This idea doesn’t include building anything, but instead, paving over everything. Buro Ehring sees some of New York’s most packed streets as pedestrian- and cycling-friendly only. A 14,540-foot-long, green-covered walkway on 30th Street could increase the desire to be in Midtown, while a similar car-free space across 61 Street and through Central Park could be a new east-to-west axis.

With all these solutions, Buro Ehring also sees the construction of cycling-specific hubs placed on the edges of the boroughs for commuters and advocates to join forces, and create solidarity. Not only that, but there could be a serious placemaking effect from the integration of these healthier cycling options. Just as the High Line spurred both high-design and community-based development along it and underneath, so too could these greener, cycling-centric spaces help influence growth throughout New York.

“A simple idea like improving the bicycle network can have a domino effect of positive impacts on the city,” said Ryan Cramer, a project manager. “The infrastructure is all in place. It’s now just a matter of implementing the solutions.”