The U.K. has released a National Design Guide to help “create beautiful, enduring and successful places.” The guide was published at the start of the month and unveiled by Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick, however, for all the “good design” the guide preaches, it is at odds with Jenrick’s actual policies.

To architects and designers, the principles outlined in the document will seem run-of-the-mill, even perhaps a little patronizing. But the guide is not for them; rather, it intends to ensure that all those involved in a project are on the same page. The focus of this design guide is on good design in the planning system, so it is primarily for:

- Local authority planning officers, who prepare local planning policy and guidance and assess the quality of planning applications;

- Councilors who make planning decisions;

- Applicants and their design teams, who prepare applications for planning permission; and

- People in local communities and their representatives.

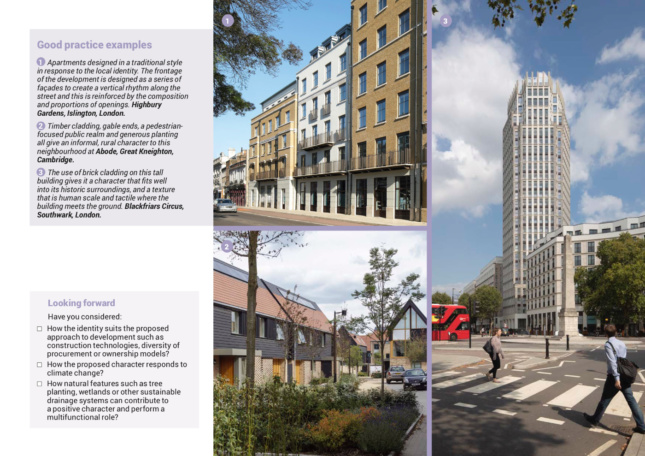

A cursory scroll through the guide reveals a lot of images—almost all houses, with pitched roofs and brick facades along with a surprising amount of churches. A design guide issued by a Conservative politician seemingly calling for Victorian and Georgian villages a does incur a momentary feeling of dread (Poundbury is featured) but thankfully the guide is much more nuanced and ultimately offers some good advice.

Ten “characteristics” for design are introduced in the guide, paying special attention to character, community and the climate:

Context – Enhances the surroundings.

Identity – Attractive and distinctive.

Built form – A coherent pattern of development.

Movement – Accessible and easy to move around.

Nature – Enhanced and optimised.

Public spaces – Safe, social and inclusive.

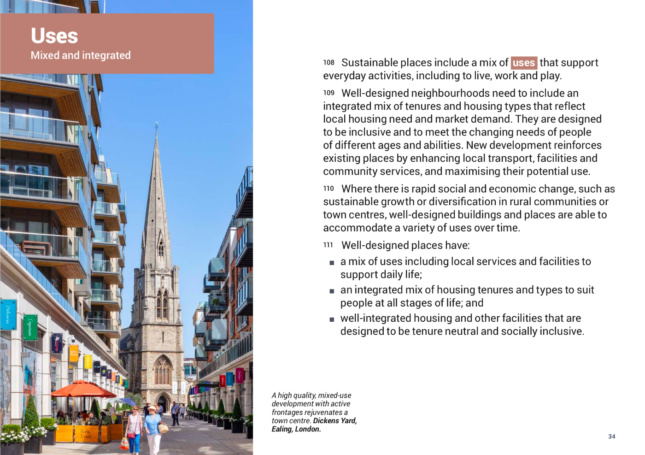

Uses – Mixed and integrated.

Homes and buildings – Functional, healthy and sustainable.

Resources – Efficient and resilient.

Lifespan – Made to last.

The guide also takes into account the contemporary context we find ourselves in and looks to the future: “We expect continuing change as a consequence of climate change, changing homeownership models and technological changes. It is likely to emerge and embed in society rapidly.”

Furthermore, there is an added focus on inclusion and community cohesion, defined respectfully as: “Making sure that all individuals have equal access, opportunity and dignity in the use of the built environment;” and “A sense of belonging for all communities, with connections and trust between them. Diversity is valued and people of different backgrounds have the opportunity to develop positive relationships with one another.”

However, for all this positive rhetoric—which will hopefully make some impact—the guide is undermined by Jenrick’s latest policy to allow homeowners to add up to two stories to their house without having to get planning permission. This is part of the Conservative party’s push to “build up not out,” and essentially allows homeowners to do what they want irrespective of their neighbors’ objections, provided the building meets council guidelines and building regulations.

Subsequently, it seems bizarre for the guide to talk about scale, height, relation to surroundings, and design quality, the latter of which will be most lacking as a result of such a policy. The guide also appears to feature mostly low-rise schemes and genuine examples of suburban sprawl with a straight face, the antithesis of building “up.”

“Publishing new design guidance alongside plans to extend permitted development rules, which allow projects to sidestep vital quality and environmental standards, just doesn’t make sense,” remarked RIBA President Alan Jones.

“Although increasing permitted development rights is a step in the right direction, they will still be subject to heritage and conservation areas and viewing corridor type constraints,” Vaughn Horsman, design director at the British practice Farrells told AN. “And whilst it supports wider densification, by the time the tangle of other constraints get overlaid, there is still very little available land and air space available for growth in London. Meaning more still needs to be done.”

Moreover, the design guide also seems to focus solely on housing. It has admittedly come from the Housing Secretary, but alternative typologies could at least be acknowledged, particularly as the industry moves towards adaptive re-use.

Despite this, the guide has been for the most part warmly received by the profession. Teresa Borsuk, a senior adviser at the London-based Pollard Thomas Edwards, told the Architects’ Journal:

[The guide] is a sound piece of work aimed at planning officers, councillors, applicants and local communities. And a lot of it is not new. But what a difficult time for its launch – with everything else going on just now; climate change, affordability, targets, undersupply, Brexit…

Speaking in the same article, Richard Dudzicki, director of Richard Dudzicki Associates, meanwhile called for an “anarchic version of the National Design Guide”:

I started reading the National Design Guide thinking to myself this is not a bad idea, but I quickly thought of the successful places I love; Farringdon in the 90s or Peckham now. They do not fit in the government’s ‘10 simple rules to good design’. The truth is very little good design or successful placemaking will fit in this dull, grey, pragmatic framework. It is about interventions. Predefining spaces will lead to failure; failure of design, failure of place and failure to create a society. Architecture as a profession should be calling out for more. In this profession, we read the brief, rip it up and throw it out of the window and try to come up with a new idea. Let’s have an anarchic version of the National Design Guide.

Finally, the guide concludes by saying that it could be altered after the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission publishes its final report in December this year. This could likely cause groans in the profession: the Commission’s re-appointed cochair, Roger Scruton, has previously voiced his distaste of modernism, and in particular, architects Norman Foster and Mies van der Rohe.

“The words ‘beautiful’ and ‘ugly’ are dangerous when referring to architecture — they expose personal bias, when our industry is more restricted than ever, by budgets, political and technical constraints,” Horsman added. “Urban homes at the scale we need today will struggle to fit everyone’s view of ‘pretty’ –having our work, almost degraded, to such terms is frustrating. “How would ministers feel about a public vote on whether they’re too ugly for the job?”

The report can be found in full online, here.