What goes into a park? We dug into the parts and pieces of landscape design to explore and illustrate the forces, material histories, and narratives that hide beneath the surface. This article is the first of three such deep dives, which includes The Gathering Place in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Hunter’s Point South Park in Queens, New York. All illustrations were done by Adam Paul Susaneck.

Santa Monica’s Tongva Park is a true product of Southern California. It certainly has a physical connection to its context—its hills and outlooks are packed with soil from construction sites in the area; its irrigation water sourced from the local runoff recycling facility; its plants were grown in regional nurseries—but in less tangible and more sociopolitical ways, too, the park bears the mark of the Golden State.

Tongva, which opened in 2013, was funded under California’s now-defunct tax increment financing (TIF) laws. The first of their kind in the U.S., California’s TIF laws went into effect in 1952 with the passage of the Community Redevelopment Act, which set a precedent nationwide for how infrastructure might be financed. Many states have since imitated the approach to establish the funding mechanisms behind massive—and often controversial—projects, including Chicago’s Navy Pier and New York’s Hudson Yards. Tax increment financing lets municipalities borrow money for developments in areas designated as “blighted” with the assumption that the developments will generate higher property-tax revenue as land values rise. Critics have argued that TIF programs have been abused to subsidize luxury developments that do little to improve the quality of life for local residents, and in 2011, while work on Tongva was well underway, then-governor Jerry Brown dissolved California’s TIF program, making the park part of the state’s final wave of TIF-backed projects.

The park benefits from Southern California’s crazy-quilt approach to urbanism, where the wealthiest communities of the Los Angeles region have remained independent cities, enabling areas like Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, and Santa Monica to invest tax revenue within their borders without sharing with the city of Los Angeles that surrounds them. Cities where the median home price is less than Santa Monica’s, ($1.6 million, more than twice the median home price for Los Angeles) may not be able to spend so lavishly on their parks.

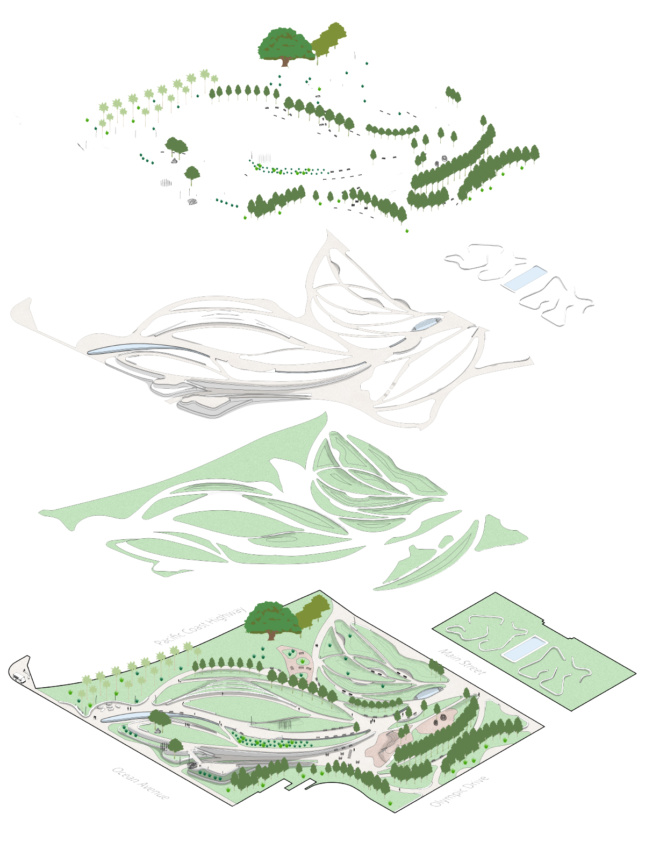

California comes through most tangibly in the park’s siting and the aesthetic decisions by the park’s designer, James Corner Field Operations (JCFO). JCFO incorporated several beloved trees that were already on the site into an arroyo-inspired plan that orients visitors toward spectacular views of the Pacific Ocean and a beach that stretches out casually, with an air of West Coast chill, just across the street.

Funding

The park was entirely publicly funded using TIF. The City of Santa Monica bought 11.6 acres of land from the RAND Corporation; besides the park, housing was built on the site and Olympic Drive was extended through it. The city spent $53 million on the property and another $42.7 million to design and build the 6.2-acre park, which includes a small area across Main Street in front of Santa Monica City Hall.

Plants

Tongva hosts more than 30,000 plants of more than 170 species, and more than 300 trees from 21 species, most grown in seven nurseries across the state; the farthest is in Watsonville, less than 300 miles up the coast. Some trees traveled even less distance: Morty, a Moreton Bay fig tree, and the Three Amigos, a group of ficus trees, pictured below, along with several palms, were preserved and rearranged on the site to fit into the new landscape. The park mixes native and non-native drought-tolerant species in zones modeled on three California ecological communities (coastal scrub, chaparral, and riparian), creating a landscape that feels familiar but avoids cliché.

Buildings

The steel cocoon-esque pavilions, pictured below, and play structures were fabricated by Paragon Steel in Los Angeles.

Furniture

Custom furniture was designed using Forest Stewardship Council–certified jarrah wood, a variety of eucalyptus usually grown in Western Australia. Off-the-shelf benches from Landscape Forms were also used.

Art

Weather Field No. 1, by Chicago-based artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, comprises a field of 49 stainless steel poles with weather vanes and anemometers attached.

Hardscaping

Aggregates in the hardscaping came from pits in the nearby San Gabriel Valley. Walls have California Gold rocks.

Water

Plants are irrigated by water from the Santa Monica Urban Runoff Recycling Facility. Stormwater from the park is also collected in bioswales, and water features recirculate potable water in closed systems.

Transit

Tongva integrates into regional transit in some of the usual West Coast ways—there are bikeshare stations and scooter access—but it’s also just a block away from one of the Los Angeles area’s biggest transit initiatives: the LA Metro Expo Line expansion. The nearby Santa Monica Station opened three years after the park and was a part of a broader regional plan, whereas Tongva was part of a separate Santa Monica–specific urban plan.

The region’s ubiquitous car culture is also present. Tongva sits at the southern tip of the picturesque Pacific Coast Highway, which extends up the shore to Big Sur, San Francisco, and beyond, and Olympic Drive, a local three-lane street, was extended along the park’s southeastern edge.

Land

The site was previously home to the RAND Corporation headquarters, which have since relocated to a neighboring block. Housing developed by the Related Companies was built on the opposite side of the Olympic Drive extension.

Infill/Terraforming

Before being cleared for Tongva, the site was dominated by the RAND Corporation’s parking lot. To create the park’s lookouts, which rise in points to 18 feet and provide views to the Pacific Ocean, infill soil was taken from construction sites around the city, tested to ensure safety, and sculpted to create accessible slopes for the site.

Project Delivery

JCFO was selected through an international competition in which 24 teams participated. After JCFO won, there were five community workshops over six months, and the scheme was presented to six review boards and commissions before site work began in 2011. Although the scheme began as a design-bid-build project, the city turned it into a design-build project midway through the process to try to speed delivery after California revoked its TIF laws.

Maintenance

The City of Santa Monica spends just under $100,000 annually on basic maintenance, plus about $20,000 annually on tree work and $10,000 annually on custodial work.

Security

Although there is no operational security technology in the park, Santa Monica has used some unorthodox activity-based surveillance strategies. After squatters set up informal camps on the park’s western corner, city agencies arranged for a food truck to occupy that area, which has since discouraged people from living there. And on top of regular maintenance costs, the City of Santa Monica spends about $330,000 annually on “ambassadors” who staff the park, answering questions from visitors and keeping an eye on activity.

As is standard in many U.S. parks, Tongva closes at night; its hours are from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.