“Tip the world over on its side,” Frank Lloyd Wright once quipped, “and everything loose will land in Los Angeles.” As a fresh L.A. transplant in the early 1920s, Wright clearly had trouble finding his bearings, yet nearly a century on, his testimony remains remarkably apt: To the uninitiated, the “fabric” of Los Angeles’s cityscape can feel improvisatory, a game board consisting of extravagantly mismatched pieces.

The very same observation can easily be applied to Hancock Park, which counts geological excavations, fiberglass mammoths, contemporary art, and, soon, Hollywood cinema among its many oddities and enticements. No fewer than three cultural institutions are currently situated on the park’s 34 acres, but they are an atomized bunch, existing together in relative isolation. However, plans are afoot that promise to join together these disparate pieces into a museological collection unparalleled in the western United States.

The prime mover is unquestionably the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), which became Hancock Park’s first cultural institution when it opened in 1965. William Pereira’s palatial yet restrained campus—originally a composition of three buildings (the Ahmanson Building, the Bing Center, and the Lytton Gallery) surrounded by reflecting pools—attempted to cast Los Angeles in the role of art-world magnet even as critics placed it at the margins. As the city expanded its influence in this arena, so, too, did LACMA expand within Hancock Park, with the museum adding buildings by Bruce Goff, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates, and Renzo Piano. More recently, outdoor artworks by Chris Burden, Michael Heizer, and Robert Irwin have signposted the institution’s desire for outward growth at the expense of a defined center.

The La Brea Tar Pits, a group of asphalt lakes from which paleontologists have exhumed the fossilized remains of Ice Age-era Mammalia for more than a century, occupy 13 acres of the park’s eastern half. In 1967, the sculptor Howard Ball created a fiberglass family of woolly mammoths along Lake Pit, the largest tar pit on the property, that dramatically raised the unusual site’s profile. A decade later, the George C. Page Museum, a quietly monumental museum and paleontological research facility designed by Willis Fagan and Frank Thornton to study and display the fossils, took up residence at the northeastern corner of the pits—as far from the LACMA campus as physically possible.

For nearly half a century, LACMA and the La Brea Tar Pits seemed entirely indifferent to one another, even as they remained cheek by jowl. Both offer as many outdoor attractions as they do interior exhibitions, which has the potential to blur user groups, if not visitor experiences. But the parkland stretching between the two campuses has never done much to smooth the jarring transition from art to paleontology.

This strained dynamic was brought into question in 2014, when construction began on the 300,000-square-foot Academy Museum of Motion Pictures at Hancock Park’s southwestern corner. Operated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the museum plans to split its programming between two buildings: the former May Company Building, a department store designed in a streamlined moderne style by Albert C. Martin in 1939 (and once briefly owned by LACMA), and the Sphere, a striking high-tech belvedere designed by Renzo Piano and featuring a 1,000-seat theater. When it opens this December, the complex will be America’s largest dedicated to the art and science of filmmaking, a craft that turned the orange groves of Los Angeles into a city of global recognition.

With this third player in the mix, LACMA and the La Brea Tar Pits independently saw opportunities to reinvent themselves and, perhaps, finally unify Hancock Park and its aggregate cultural and recreational offerings.

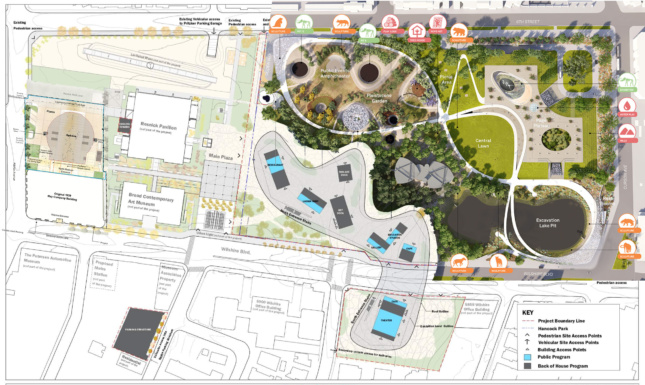

In August 2019, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC), which manages the La Brea Tar Pits, announced it had selected three firms to develop master plans that would take stock of the site’s invaluable contents while updating its outdated visitor experience. A few months later, after staging a public exhibit of the projects, NHMLAC elected to push ahead with multidisciplinary firm WEISS/MANFREDI’s master plan. The design calls for the preservation of the site’s most locally beloved elements, including Lake Pit and the original Page Museum, and ties them together with a 3,200-foot-long looping pedestrian path.

Calling the Page “introverted,” architect Michael Manfredi summarized the scheme’s intention to pull back the curtain on the museum’s ongoing paleontological research: “Because Hancock Park is a public space, and not a nine-to-five destination, our master plan hopes to stretch the hours of engagement by revealing the hidden life of the museum to the public without [visitors] ever stepping inside; to make the science more visible, and make [the displays] a more active element of the park rather than mere inert objects.” Manfredi conceded that the scheme is still in development, and his team expects to incorporate more public input in the next design rounds; so far, the joint effort has collected more than 2,100 survey responses from the local community.

Meanwhile, LACMA’s own redevelopment plan has been met repeatedly with public and critical scorn. Since assuming the museum’s directorship in 2006, Michael Govan has been emphatic about his desire to make his mark with a grand new building. In 2013, he unveiled plans to replace Pereira’s midcentury pavilions and Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer’s mid-1980s Art of the Americas building with a tabletop design spanning Wilshire Boulevard by the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. Only Piano’s 2008 Broad Contemporary Art Museum and 2010 Resnick Pavilion—a campus in themselves—would be spared.

Though there have been a handful of public meetings following each successive plan (the project has undergone drastic revisions since first being unveiled), local groups contend they have been purposefully left out of the decision-making process by the parties in charge—namely LACMA, Zumthor’s office, and the county’s Board of Supervisors. Among the most prominent of these is the nonprofit Save LACMA, whose mission statement touts the “enormous pool of goodwill, sentiment and investment” it has accrued in its drive to protect the museum’s beleaguered buildings. Like its ally the Citizens’ Brigade to Save LACMA, Save LACMA has decried recent cost estimates putting Govan and Zumthor’s project at $750 million, with $125 million coming from the County of Los Angeles.

Rubbing salt in the wound, another report alleged that the new LACMA would contain 10,000 square feet less exhibition space than did its predecessor. Summing up the brouhaha in the Los Angeles Times, art critic Christopher Knight (who just won a Pulitzer for his take on the LACMA controversy) needled the expansion and dubbed it the “Incredible Shrinking Museum.” LACMA fanned the critical flames when, in early April, after stay-at-home orders had been issued to reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus, it began dismantling the Bing Center. Later that month, as if capitalizing on the controversy, the Citizens’ Brigade unveiled alternative proposals to the Zumthor design, which varied in tone (though nearly all were wistful) and feasibility (with more than one barely-there provocation).

None were as audacious as Zumthor’s parti, which is nonetheless poised to improve on LACMA’s current campus. As grand as the Pereira buildings may have been in their day, they formed a visual barrier across Hancock Park’s southern perimeter and created an inelegant walking path along the campus’s expanding east-west axis. From the west, visitors had to scale the Ahmanson Building’s pompously wide stairs before stumbling onto the main plaza, later blocked from Wilshire with the addition of the Arts of the Americas building.

Zumthor’s decision to lift all the exhibition spaces and other museum functions into the air (and over Wilshire) grants visitors unfettered access to the central axis of the park. At LACMA in February, Govan quipped that visitors to the future Hancock Park will be able to go from “movies to mammoths” without paying an admission fee. It’s striking that this consequence of Zumthor’s planning has survived all the project’s alterations; clearly, critic Christopher Hawthorne was correct in saying, all the way back in 2013, that the design was less aloof than his peers made it out to be.

A composite site plan of all three ongoing projects reveals a Hancock Park that bears little resemblance to its present self: A flock of Piano-designed structures congregates in its western half, absorbed in their own symmetries; Zumthor’s spaceshiplike LACMA retreats from the park’s center and straddles Wilshire Boulevard to the south, touching down on a one-acre park (currently a parking lot owned by the museum); and, while still subject to change, the pedestrian loop winding through WEISS/MANFREDI’s La Brea Tar Pits master plan echoes LACMA’s curves, as if the two entities were at last ready to tango after decades of bumping elbows.

This gradual movement toward greater cohesion tracks with two other L.A. projects currently in the works. The first is the addition of seven new stations to the Metro’s D Line along Wilshire Boulevard, representing a major improvement to the city’s underdeveloped public transportation infrastructure. The Wilshire/Fairfax station, sited directly across the street from Hancock Park, is slated to be completed in 2023, three years after the Academy Museum and one year before LACMA (though a construction timeline for the La Brea Tar Pits master plan is still in the works, one may expect that it will attempt to align with its neighboring developments). According to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, or Metro, LACMA has indicated it would finance a second station entrance on its campus, which would connect the block to the city at large more seamlessly than ever before.

Yet even Metro has felt the pressure to accelerate its construction timeline in response to a second, even larger citywide goal: the 2028 Summer Olympics, the third time in the event’s modern history that the games will be held in Los Angeles. As if impelled to replicate the success of the previous iteration in 1984—considered the only profitable games in modern Olympic history—Los Angeles is currently abuzz with construction on large-scale developments, including the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art (see page 30), SoFi Stadium, and the renovation of Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Against this backdrop, the transformation of Hancock Park into a single, coherent block of art, film, and prehistory in time for the Olympics would be a major boon for the city’s title as a cultural capital. (Such a consolidation might even compel Angelenos to finally call the park by its official name, which it shares with a well-heeled residential cluster to its east.)

At the time of this writing, Hancock Park is not much to look at. Some elements are dulled by years of neglect, others too shiny for lack of occupation, and others still scarred by the recent violence of demolition. Yet a little patience will likely yield an outsize reward: a true microcosm of a city possibly too large in size and cultural importance to take in by any other means.